Poets and poetry are boundless and eternal. India’s ongoing

turmoil has people, particularly the young, from all classes and communities,

giving vent to their anger and aspirations through words and verses, reviving

some old and long-forgotten, and creating new ones.

Grannies and mothers with babies in arms braving biting cold

have come out in this winter of discontent.

Media last week captured a diminutive Sociology student,

Gayatri Borkar, sitting amidst the protestors at Mumbai’s Gateway of India,

feverishly churning out copies on an old typewriter of poets old and new —

Varun Grover, Nagarjun, Dushyant Kumar and Habib Jaleeb. And Rahat Indori who defiantly

asks: “Kisi ke Baap Ka Hindustan

Thodi Hi Hai? (Is India anyone’s paternal property?)”.

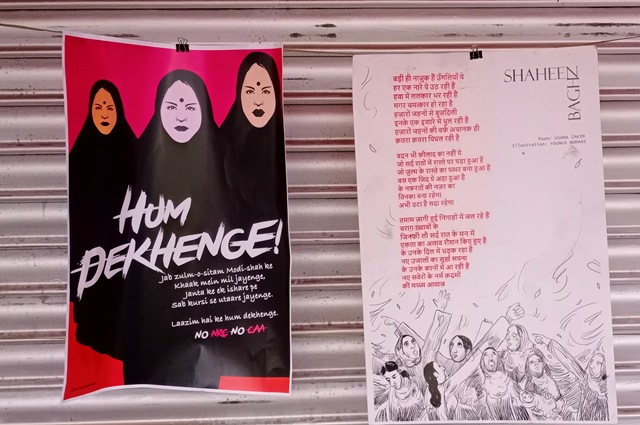

Among them was “Hum

Dekhenge”, the iconic poem of Faiz Ahmed ‘Faiz’. It is doubtful if

this Marathi girl would understand Faiz’s Persianized-Urdu, its words and certainly,

their import. But to judge her and thousands protesting for their ignorance

would be downright unfair.

Restricted to the Urdu-speaking literate classes, Faiz has

returned to India, in a manner of speaking, long after he left for Pakistan and

died in 1986. And long after impact of the ideology he espoused has steeply

declined. But Faiz, like others, is about sentiment, not substance.

This reminds of Subhas Chandra Bose’s “Kadam Kadam Badhaye Ja” of the1940s

and “We shall Overcome” Indianized

as “Hum Honge Kaamyaab” of

the 1970s. Those were different eras in the last century.

Faiz inspired. My interview with him during his last India

visit was actually a non-interview. In the 25 minutes or so that we set across,

he was on telephone for over 22. Barely one question was answered. When the

next visitor came, he waved me off, endearingly: “Oh, yaar kuchhbhi likh dena.” It became a cook-up job.

A “protest poem” against an intolerant military order running

in the name of religion, “Hum Dekhenge” has remained the most popular

poem in Pakistan’s underground society, and for some very good reasons. But do

those reasons apply to the present-day India?

Frequently in exile for protesting oppressive regimes, Faiz

had written it in 1979 against military dictator Ziaul Haq. It was promptly

banned. All copies were destroyed, till on Faiz’s death in 1986, Iqbal Bano,

dressed in a black saree that Zia had outlawed, sang it in a small

auditorium in Lahore. It brought the house down with excitement. The police

seized all recording of this poem save one that was smuggled out of Pakistan

and it is now available on Youtube. It is indeed inspiring.

But

can it be adopted in India? The language is alien to most Indians today.

Then, Faiz is identified with Communism. Although he belonged to both India and

Pakistan, Faiz’s nationality and ideology are anathema to India’s current

ruling classes and large sections of populace they have successfully seduced.

There

is bound to be hostility to Faiz’s invocation of Islamic symbols and imageries.

He was an atheist and his deliberate use of them only infuriated the

conservatives. And conservatives, aggressive and intolerant, are ruling all

across the world today.

These

classes are worried about spread of culture they do not approve of. Saare Jahan Se Achha of Muhammad Iqbal

is arguably third-most popular Indian song, both as a lyric and a martial tune,

after Jana Gana Mana, the national

anthem and Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s “Vande Maataram”. Indian conservatives, Hindu and Muslim, have

had problems with all three through the long years of the freedom movement and

thereafter.

Hum Dekhenge

comes in more complex times that are less ideological and more

‘pragmatic’. They are more difficult

judging from the way words “Inquilab’

and “Azadi” that were part and parcel

of India’s freedom movement have, ironically, come to mean ‘secession’ and are thus,

“anti-India”.

The

extent to which the current ethos has over-whelmed ideas that have been

inclusive and pluralist is evident from the Indian Institute of Technology,

Kanpur, one of the country’s best institution of higher technological learning,

forming a committee to judge if “Hum Dekhenge”, sung at a campus rally,

has “anti-Indian” content. Elsewhere, the song has been declared

“anti-Hindu.”

Writers-poets

Gulzar and Javed Akhtar have stressed that a song written against Pakistan’s

military junta couldn’t have ‘Indian’ or ‘Hindu’ context. Javed termed the controversy “absurd and

funny”.

The

verse that gave offence was: Jab

arz-e-khuda ke ka’abe se, sab buut uthwaae jaayenge / Hum ahl-e-safa

mardood-e-haram, masnad pe bithaaye jaayenge / Sab taaj uchhale jaayenge, sab

takht giraaye jaayenge/ Bas naam rahega Allah ka… (From the abode of God,

when the idols of falsehood will be removed/ When we, the faithful, who have

been barred from sacred places, will be seated on a high pedestal/ When crowns

will be tossed, when thrones will be brought down, only Allah’s name will remain.)

The

objection was to the word “buut” (idol) which was taken as a reference to idols

of deities that Hindus worship and to Allah and was therefore, a communal

insult. India, it would seem, is not offended by Faiz’s “communalism”, but by his

pluralist message in 2020.

Pakistani

writer Khaled Ahmed laments India’s “decline into religion” when

saner Pakistanis are looking up to an India that they have known and admired

for its all-in socio-political ethos.

This

reminds of Pakistani poetess, late Fehmida Riaz, who chided Indians with her

poem “tum bilkul hum jaise nikle, ab

tak kahan they bhai?” (You turned out to be like us, brother. Where

were you all this while?) Will this

indignation go unrealized, un-responded in India?

This

Pakistani ‘sedition’ is not aimed only at India. A video of students chanting Sarfaroshi ki tamanna at the recent Faiz

International Festival in Lahore is on the Internet. The lines were written by

Ram Prasad Bismil, who fought and died along with Shaheed Bhagat Singh. This is new India. And perhaps, a new Pakistan (not to be

confused with Imran Khan’s Naya Pakistan promise).

Let this be said, whatever be the outcome of the protests over the present government’s two controversial moves — adding to the accumulated angst on many other issues — this combined muse of the old and the new, even if it falls silent for now, shall revive another day.

The writer can be

reached at mahendraved07@gmail.com