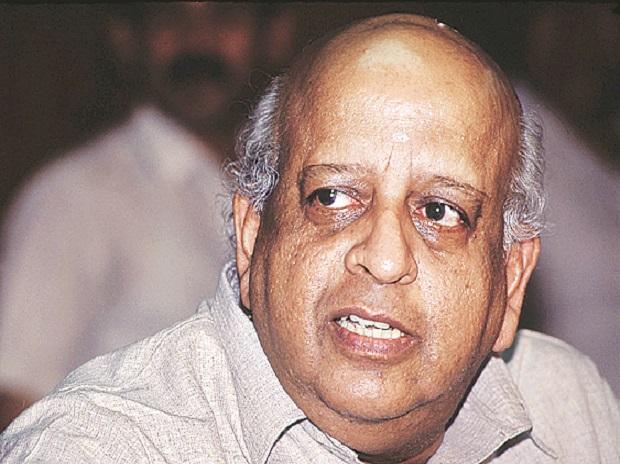

As cabinet secretary to VP Singh, Seshan had to deal with

the kidnapping in Kashmir of the daughter of home minister Mufti Mohammed

Sayeed. Moosa Raza, an IAS officer of the Gujarat cadre, who was then the chief

secretary of Jammu and Kashmir, recalled that Seshan “used strong and

forceful language when dealing with his subordinates, but was meek and obedient

with his bosses”, and that Seshan meekly gave in to Vishvanath Pratap

Singh:

“In those days

before the advent of mobile phones, we communicated only through landlines,

which could be easily tapped at the telephone exchange.

It was suspected that many of those who worked at the

exchange were sympathisers of the militants.

(Then Cabinet secretary T N) Seshan insisted that I

speak with him only in Tamil, as it was unlikely that the exchange in Kashmir

would have any Tamil-speaking staff sympathetic to the militants. (Moosa Raza

was a Tamilian, a Navayat Muslim from Tamil Nadu).

Our efforts were

to keep the negotiations going through the intermediaries and, in the interim,

locate the safe house and get her released through commando action.

Both the state police chief and the intelligence

officials were opposed to the idea of using military force; they said it would

pose a grave risk to the life of the hostage.

The police and paramilitary forces stepped up their patrolling,

and photos of Rubaiya Sayeed were widely circulated.

Public opinion was mobilised to put pressure on the

militants and the JKLF.

Statements were issued by opinion makers and political

personalities, deploring the kidnapping of an innocent girl as an un-Islamic

and unethical act.

The CM (Dr Farooq Abdullah) was rather unhappy at

the pressure being brought on the state government by the Centre to release the

militants in exchange for the home minister’s daughter.

He was apprehensive that this would set a trend and lead

to more kidnappings in the future.

I was told that not only the home minister but also his

colleagues were troubled by the prolonged negotiations and wanted the matter to

be resolved as quickly as possible.

In the first couple of days after the kidnapping, there

was widespread condemnation of it in the press.

But as the days passed, there was a noticeable shift

towards the primary objective of getting the girl released.

There was sympathy for her plight, and the pressure to

release the militants and free her mounted.

I received a call from the Cabinet secretary at 1.30 am

on 13 December.

In a rather stiff and formal tone, he said, ‘This is the

Cabinet secretary to the GoI, T N Seshan, speaking to the chief secretary of

the state of Jammu and Kashmir, Mr Moosa Raza. I am speaking from the chamber

of the prime minister of India.’

‘The GoI desires the state government to note that it is

their undiluted responsibility to ensure the safe release of the hostage

without any injury to her, and we expect that all action you take will be

consistent with this requirement.’

Having made this pontifical statement from the throne as

it were, he abruptly disconnected.

The operative words were ‘at all cost’.

In other words, ‘release the militants’.

This also ruled out commando action, even if the police

and the IB were to locate her whereabouts.

‘Without injury to her’ could only imply that.

Some of my advisors believed there was an implicit threat

in the statement: If we could not get the girl released immediately, the state

government would be held squarely responsible for the failure and may even be

dismissed.

But it was still not clear to me whether the GoI had

agreed to an immediate release of the imprisoned militants and desired us to

accept the militants’s terms, or not.

After waiting for half an hour, I rang up the Cabinet

secretary in the hope that he would have returned from the PM’s office by then

and would clarify the sudden volte face.

I spoke to him in Tamil and asked to know the reason for

the change in stance when I had almost concluded the negotiations without any

loss of face to the government.

I also asked him about the implications of his message to

me from the PM’s chamber.

Seshan was aware that he was a lame duck Cabinet

secretary and his days in the Rashtrapati Bhavan annexe were numbered.

He could not stand up to a PM with an imperial streak in

him.

The Raja of Manda (Vishwanath Pratap Singh) had his way.

That last conversation with Seshan told me all I needed

to know about him: Here was a man given to using strong and forceful language

when dealing with his subordinates, but meek and obedient when it came to his

bosses.

The news was received by the CM and me with grave

concern, as it negated all the efforts at negotiations made until then.

I felt that since the girl could be brought back without

an exchange, it would be in the national interest to wait.

But my arguments did not find any favour in Delhi.

The CM was so perturbed by this unwarranted intervention

that he contemplated submitting his resignation immediately.

I informed the governor of the latest developments and

the CM’s state of mind.

Both (then governor) General (V K) Krishna Rao and I were hard put to dissuade him from such a

precipitate action in the midst of a crisis.

We were to release the five militants to the three

mediators, withdraw the police from certain localities and wait for three hours

for Rubaiya to be handed over to us.

This proposal, fraught with unpredictable complications,

was not acceptable to us.

I pointed out that once we had released the militants, we

had no guarantee that the JKLF would honour its side of the bargain,

particularly when there was a gap of three hours.

Anything could happen during those crucial hours.

Even if we trusted them to keep their side of the

bargain, we had no way of knowing whether some other militant group opposed to

the JKLF ideology (and there were many waiting on the sidelines for an

opportunity) would take advantage of the situation and hijack the girl while

she was on her way to Sonawar.

Dr Abdullah, who had all along been opposed to the

release of the militants, was even more upset at this turn of events.

It was under extreme pressure from the Centre that he had

even agreed to release the militants.

But having to wait for three hours before knowing whether

the government had been taken for a ride was not the kind of situation that

either he or I were prepared to face.

He was ready to tender his resignation there and then.

I think he spoke to the governor, who once again perhaps

restrained him from doing so.

At 2.30 am, I met the CM and apprised him of the Cabinet

secretary’s approval and my subsequent conversation with him.

He was dismayed.

‘They will destroy Kashmir,’ he said.

I could hear the agony in his voice.

But reluctantly, he told us to go ahead and finalise the

arrangements.

The next three hours were excruciating.

Even though I had obtained the necessary approvals, I was

aware that these were all verbal.

If anything went wrong, and for some reason the girl did

not turn up, my head would be on the chopping block.

There was every chance that everyone would wash their

hands of the responsibility, and I would be accused of having released the

militants off my own bat.

At 7.15 pm, a car pulled up at the house, and Rubaiya

appeared.

She seemed to be in good health, though shaken by her

ordeal.

Neither I nor the police ever got the opportunity of

debriefing her.

Rubaiya remained inaccessible to state and central

intelligence.

She could have given us valuable information, but I never

even learnt where she had been held captive.

Seshan called to congratulate me on the successful

conclusion of the episode.

He was effusive in his praise and asked me to convey the

government’s appreciation to my colleagues.

A couple of years later, I met Seshan, who was then chief

election commissioner, at the VIP lounge in Delhi airport.

As we walked towards the security clearance gate, I asked

him, ‘I have always wondered about the sudden change in your approach when you

dictated that ultimatum to me on the morning of 13 December.

What was the reason for that?’

‘The game was much bigger,’ he said, with a sardonic

smile.

‘The target was much higher.’

‘And what was that?’ I asked.

His reply is a story for another day.

The law and commerce minister in the Chandra Shekhar

government, Subramanian Swamy, appointed TN Seshan as the Chief Election

Commissioner in 1990. The two knew each other well from their Harvard days;

Seshan had been a Mason Fellow at Harvard, and he took several courses taught

by Swamy. Seshan, who prided himself on his culinary skills, would cook meals

for Swamy and his family. Prime Minister Chandra Shekhar had his misgivings,

but went along.

Now that he had the protection of a statutory position

and could not be harmed by politicians or civil servants any more, Seshan was a

man transformed. Thundering that he could be “removed only by an Act of

God”, Seshan went hammer and tongs after corrupt politicians, and cleaned

up the electoral system.

The same man who sucked up to dubious politicians like

his minister Bhajan Lal, now thundered: “I eat politicians for

breakfast”.

The same man who offered blandishments to journalists at

the tax-payers expense, and who hosted lavish alcohol-filled parties for

reporters, in order to influence their coverage of the Bofors scandal, now

dubbed all journalists as corrupt.

When prime minister PV Narasimha Rao subtly tried to

influence him, TN Seshan banged down the phone on the prime minister, shouting

at him: “I am the Chief Election Commissioner of the Indian nation, not of

the government of India or of the prime minister”.

He was dubbed Al Seshan, and Lalu Prasad coined the

phrase: “Seshan versus the Nation”. TN Seshan accused cabinet

ministers Sitaram Kesari and Kalpanath Rai of influencing voters, and told

prime minister PV Narasimha Rao to drop them from his cabinet.

There was a widespread backlash among politicians who

accused Seshan of exceeding his authority. There were numerous feuds between

Narasimha Rao and Seshan, and the prime minister and other politicians wanted

to rein in Al Seshan.

Several politicians wanted to move a resolution in

parliament to impeach Seshan. The wily but suave prime minister PV Narasimha

Rao realized the damage that an impeachment motion would do to the nation, so

he quietly quashed these impeachment efforts in parliament.

PV Narasimha Rao discovered that there was nothing in the

law which prevented him from appointing additional election commissioners. So

prime minister PV Narasimha Rao appointed MS Gill and GVG Krishnamurthy as

additional election commissioners too. A furious Seshan called MS Gill and GVG

Krishnamurthy donkeys, and blocked their entering the building of the Election

Commission.

Seshan posed for magazine covers flexing his biceps, and

approached the Supreme Court to have them removed from office. But a five judge

Constitution bench of the Supreme Court dealt a stinging defeat to Seshan,

ruling that MS Gill and GVG Krishnamurthy had powers and voting rights equal to

Seshan.

Surprisingly, the one politician whom Seshan did not

accuse of misdemeanor was J Jayalalithaa, even though she harshly criticized

him in public. In fact, her AIADMK cadres roughed up Seshan, and trashed his

room. When Seshan did not retaliate even after being roughed up by

Jayalalithaa’s followers, he was asked by a journalist: “Is this because

you are Tamil Nadu Seshan – your initials TN say so?” Seshan tried to have

this journalist arrested, but was put in his place by this journalist’s lawyers.

When reporters phoned him at his home, he would answer in

the grand manner of an English butler: “Mr Seshan is not available”.

When they pointed out that he himself was on the line, he would elaborate:

“I am not saying that Mr Seshan is not at home, which would be a lie. I am

saying that Mr Seshan is not available to give you any information”.

Hot on the heels of a story, the self-proclaimed

second-most important person in the country, Dileep Padgaonkar, phoned Seshan

late at night to get his version. Seshan banged the phone down on Padgaonkar.

The rest of the night, Seshan kept on phoning Padgaonkar, and cut off the line

as soon as Padgaonkar answered.

Seshan and his wife Jayalakshmi (they had no children)

lead a spartan, abstemious life. He spent most of his civil service salary on

donations to charitable causes, paying the school fees of hundreds of poor

children, and on buying books. He had a vast personal library of thousands of

books on a diverse range of subjects, especially on economics and political

science.

His wife Jayalakshmi was gracious and hospitable – her

father was a university vice chancellor, and she was a scholar and connoisseur

of classical music – and I wonder how much more obnoxious TN Seshan would have

been if not for her tempering influence.

He was highly intelligent, and amazingly well read on a

wide range of topics – and he made sure everyone knew how well read and

scholarly he was.

He was a stickler for punctuality and cleanliness. He

would throw people out of his office if they were even a minute late. He

frequently bragged – The toilets in my ministry are so clean that you can have

your lunch in them.

He was a know it all, giving his advice on every topic

under the sun to all and sundry. He would keep sermonizing to young women

reporters covering his ministries about why they should get married.

He was extremely status conscious, and always asked

everyone about their sub-caste, and their professional seniority, so that he

could either kowtow to them or snub them.

He was a publicity hound and always sought to be in the

headlines. He claimed that he was more popular than Amitabh Bachchan. He

thought he would give ‘quotable quotes’ to the media, but he ended up sounding

juvenile.

As soon as he became Chief Election Commissioner in 1990,

he thundered: “I don’t get a salary of 9000 rupees a month and a status of

a supreme court judge for nothing”, inviting sniggers since a salary of

9000 rupees was common in the middle rungs of the corporate sector.

While delivering a memorial lecture for my maternal

uncle, he made juvenile and puerile statements: “There are no statesmen

any more; only the Statesman newspaper. There are no titans any more, only the

Titan wrist watches”.

He bragged that he was a fantastic cook. He was a great

connoisseur and patron of Carnatic classical music, about which he was deeply

knowledgeable, as was his wife. He often said: “We Palakkad Iyers are

known for four C traits – great Carnatic musicians, top notch Civil servants,

excellent Cooks, and big Crooks”.

He was a deeply religious follower of the Kanchipuram

Shankaracharya. When the Shankaracharya passed away, Seshan demanded Dhirubhai

Ambani’s personal aircraft so that he could immediately fly to Kanchipuram. A

huge furore broke out. Seshan called a press conference, and wrote out a cheque

in favour of Dhirubhai Ambani.

There were also whispers about TN Seshan having received

valuable gifts from Sathya Sai Baba, of whom he was a devotee.

Seshan prided himself on his astrological and palmistry

skills, but his own predictions for himself did not come true at all.

He announced widely that his horoscope forecast that he

would either become the president of India or the Secretary General of the

United Nations.

In fact, Seshan had even threatened prime minister PV

Narasimha Rao – “My next job is going to be either president of the nation or

secretary general of the United Nations, and so you had better not try to harm

me”.

But Seshan received a massive drubbing when he ran for

president against KR Narayanan in 1997, getting the votes of only a few

legislators from the Shiv Sena.

Seshan invited ridicule when he accused KR Narayanan of

fraud, asserting: “In some places he has mentioned his name as KR

Narayanan whereas at other times he has mentioned his name as Narayanan

KR”.

TN Seshan spread a rumour that he would be appointed a

governor. When the press questioned him, he replied: “My wife would not

appreciate being called a governess”.

He made pathetic attempts to enter politics, abjectly

begging for support from the very politicians whom he had vilified when he was

election commissioner. Every political leader snubbed him. He was soundly

defeated when he stood for parliament against Lal Krishna Advani.

After all his attempts to enter politics failed

miserably, Seshan and his wife Jayalakshmi retired to an old age home in

Chennai. They had no children, and few friends.

He donated most of his civil service pension to numerous

charitable causes, paying for the food and education of hundreds of poor

children. In fact, when Jayalakshmi and Seshan were getting married, the

astrologers predicted that they would have no children. Seshan had then taken a

sacred vow that he and his wife would bring up all needy children as their own.

The nation owes TN Seshan a debt of gratitude for

cleaning up the corrupt electoral system. He also did some good work when he

was secretary in the ministry of environment and forests.

But the fawning accolades in the media do not mention how

he destroyed the careers of many diligent civil servants in order to please his

political masters, nor his role in trying to cover up the Bofors scandal.

Shri Surendra Singh, an IAS officer of the 1959 batch,

who became Cabinet Secretary five years after TN Seshan, recollected:

”

TN Seshan ruined or tried to ruin the career of a number of outstanding

officers who did not give in to his unreasonable demands.

One of my

brushes with him happened when he was Secretary – Environment and Forests, and

I was Principal Secretary, Industries, in the state of Uttar Pradesh.

The Environment

and Forests ministry had issued an illegal order relating to the Doon Valley.

When they did not agree to retract it, the Uttar Pradesh state government filed

a petition in the Supreme Court.

TN Seshan sent

for me and threatened to ruin my career if the petition was not withdrawn.

We stuck

to our guns and won our case in the Supreme Court.

Luckily for me,

TN Seshan was not in a position to do me harm. I am aware of several such

instances. “

TN Seshan was very honest in money matters ( in fact he

donated most of his salary and pension to bringing up hundreds of poor children

), but he was not a man of conviction. During his long career in the IAS, he

stretched rules, procedures and conventions to their limit in order to please

his political masters – but without actually breaking the letter of a single

rule.

A very senior contemporary of his in the civil services

summed him up accurately: “TN Seshan kissed a lot of arses, but he

buggered a lot of arseholes too”.