To understand fully what the mandi farmers market system is we need to look back at the history of India’s agriculture and follow it through to today while acknowledging the reforms it has faced over the last century.

The promise of regulated marketing has been enshrined in a range of legislation and in different states Agricultural Produce Marketing Regulation (APMR) Act. This act was passed by state governments after independence in the 1950s and 60s. Agricultural Produce Market Committee, otherwise known as APMCs, is a marketing board established by state governments in India to ensure farmers are safeguarded from exploitation by large retailers, as well as ensuring the farm to retail price spread does not reach excessively high levels. APMCs are committees regulated by states through their adoption of an Agriculture Produce Marketing Regulation (APMR) Act.

Now, this is where the mandi farmers market system comes in. Unit 2020, the first sale of agriculture produce could occur only at the market yards (mandis) of APMCs. However, after 2020 with the passing of the Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, which allowed farmers to sell outside APMC mandis as well as across different states of India, in turn, removing a safeguarded from exploitation by large retailers.

History

The concept of India’s Agricultural Produce Marketing Regulation dates back to the British Raj, the role of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent, it was in 1886 when India established its first regulated market, Karanja. In 1887, under the Hyderabad Residency Order, they passed their first legislation, the Berar Cotton and Grain Market Act, which empowered British residents to declare any place in the assigned district a market for sale and purchase of agricultural produce and constitute a committee to supervise the regulated markets. This Act became the model for enactment in other parts of the country. The first farm produces to attract the attention of the government was raw cotton. This was due to the concern of British rulers to make available the supplies of pure cotton at reasonable prices to the textile mills of Manchester (UK).

The concept of a mandi farmers market system was first introduced in 1928, where the Royal Commission on Agriculture wanted regulated markets. One of the measures taken to improve the situation was to regulate the trade practices and to establish market yards in the countryside- similar to the mandi system we know today. One of the first implementations of the government-regulated agricultural markets—now known as APMC- is due to Sir Chhotu Ram, a farmer leader and the then Development Minister in the provisional government of Punjab. The Punjab Agricultural Produce Markets Act, which sets up APMC in Punjab was initiated by him in 1939. In pursuance, the Government of India prepared a Model Bill in 1938 and circulated it to all states; however, it was not until India’s independence in 1947 that any progress was really made.

In the 1960s, when India was a newly independent country, many Indian citizens were starving due to food shortages. Adding on to the already existing hunger—droughts made the situation even worse. To fix this problem, the government started the Green Revolution, in which it tried to modernise Indian agriculture. The Government took the help of advisors from the United States and introduced several reforms in agriculture. In fact, during the Green revolution, India had a food surplus.

The Indian Government decided to go back to the 1928 report and developed a nationwide food marketing system to ensure fair prices, which differs from state to state. Essentially, farmers take their produce to wholesale markets called APMC Mandis to sell their produce to traders through open auctions with transparent pricing.

During the 1960s and 1970s, most of the states in India enacted and enforced APMR Acts, which meant, all primary wholesale assembling markets were brought under the ambit of these Acts. Well laid out market yards and sub-yards were constructed, and for each market area, an APMC was constituted to frame the rules and enforce them. Thus, organised agricultural marketing came into existence through regulated markets- otherwise referred to as mandis.

APMC Mandi Farmers Market System: Inefficiencies and Reforms

APMC system is not perfect and has come with its own problems. Up until 1991, the APMC markets were in their prime and it was referred to as the “golden period”. Over time there was a steady loss of growth in the market facilities. By 2006, it had declined to less than one-quarter of the growth in crop output, of which past 2006, there was no further growth. This increased the problems of Indian farmers as market facilities did not keep up with the increase in output, while regulation did not allow farmers to sell outside the APMC market.

Subsequently, farmers were left with no choice but to seek the help of middlemen. Due to poor market infrastructure, more produce is sold outside markets than in APMC mandis. The net result was a system of interlocked transactions that rob farmers of their choice to decide to whom and where to sell, subjecting them to exploitation by middlemen. Over time, the function and concept of APMC markets have been transformed from infrastructure services to a source of revenue generation for the middlemen.

Things got worse, as the market committee has excessive powers to give out licenses to traders. The licensed commission agents started forming cartels, in which they collectively decided the prices at which they would or would not buy the produce from the farmers. This, therefore, meant that the farmers were left with minimal options—leading to the creation of what supporters of the farm bill today call “mandi mafia.”

However, In the year 2003, the government brought some reforms allowing for better liberalization in the Model APMC Act. The Indian Economic service described the reform as:

“The Model APMC Act, 2003 provided for the freedom of farmers to sell their produce. The farmers could sell their produce directly to the contract sponsors or in the market set up by private individuals, consumers or producers. The Model Act also increases the competitiveness of the market of agricultural produce by allowing common registration of market intermediaries.”

Modi and the Mandi System Today

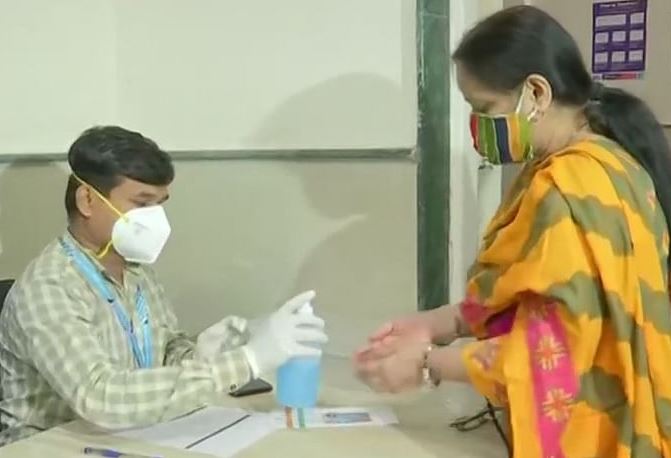

According to data by NSSO, around 6% of farmers get MSP (can be even more), who mostly sell their produce in state-government regulated mandis, and 94% of farmers sell outside mandis. Therefore, already the majority is selling outside the markets. Moreover, in the new act, there will be no tax outside APMC pushing more farmers to leave the mandis and opt for the trade markets, eventually leading to the collapse of the Mandi system, especially due to the effects of COVID-19.

However, the biggest threat to the farmers is that markets outside APMC do not provide a safeguard/ a Minimum Support (MSP)—they work on the principles of supply and demand—therefore if the prices fall too low, the farmers are losing money. The lack of safeguards/ support for farmers will highly likely allow the rich traders to exploit economically vulnerable farmers.

Furthermore, the tax in the APMC Mandis is collected by the state government, if this system collapses, the states won’t be receiving any taxes from the sale of agricultural produce. Moreover, agriculture currently is on the state list, however, the new act gives the centre the power to regulate agriculture across India, making the federal structure of the country in question.