A book written over a century back about Amritsar’s Jallianwala Bagh and two other massacres in British-ruled Punjab has lessons for the people and the rulers alike, of what has become of the Subcontinent today.

These lessons later; about the book first.

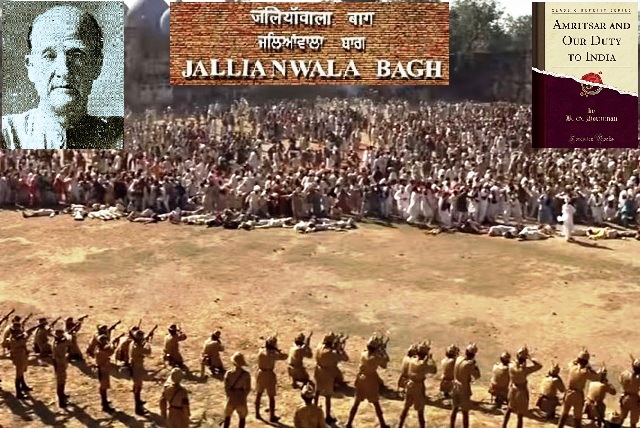

Amritsar and Our Duty to India was the first expose in book form published within months of the events. It was accidentally discovered on the Internet and traced to the archives of an American university by Dr Mrinal Chatterjee, a writer and regional director at the Indian Institute of Mass Communication (IIMC) Dhenkanal, Odisha.

The Cornell University bought it with “the income of the Sage Endowment, the Gift of Henry W. Sage.” The university says that “there is no known copyright restriction in the United States on reproduction of its text.”

The name of the book’s author may ring the bell among the old timers in India and Britain. Benjamin Guy Horniman, a Briton who became known as a “friend of India”, was editor of The Bombay Chronicle. The book carried photographs of the actual happenings at Jallianwala Bagh that he had managed to smuggle out.

Publishing reports and comments in his newspapers and in the British Labour Party’s mouthpiece the Daily Herald, Horniman successfully defied General Michael O’Dwyer who, as lieutenant governor, had imposed press censorship in the Punjab province.

Horniman called out General Reginald Dyer in whose presence hundreds of unarmed civilians, including women and children, were fired upon, calling it ‘Dyerarchy.’ The word gained currency in both India and Britain.

An angry British Indian government deported him to England. He was not allowed to return. Till in 1926, when he simply boarded a ship and landed in Madras.

Horniman’s objective was to inform world, in particular implore the British people, to question the justification given by Gen Reginald Dyer who had emerged a hero to many lawmakers. The British Parliament debated at length, but finally tilted in Dyer’s favour. The House of Lords, especially, ‘exonerated’ him.

A century on, the book makes fascinating reading. Horniman calls the Amritsar massacre an ‘indelible blot on British rule in India’.

“It is impossible to believe that the people of England could ever be persuaded that a British General was justified in, or could be excused for, marching up to a great crowd of unarmed and wholly defenceless people and, without a word of warning or order to disperse, shooting them down until his ammunition was exhausted and then leaving them without medical aid.” he wrote.

Quoting General Dyer’s defence, Horniman exposes the British hypocrisy: “He felt his orders had not been obeyed. Martial law — which did not then exist — had been flouted, and he considered it his duty to disperse the crowd by rapid fire.”

Horniman reminded the British people of their responsibility and duty. “The ‘Dyerarchy’ did not end with the Jallianwala massacre, the disgrace was brought to further depths” by what followed during the six weeks of administration of the martial law under Gen Dyer in Lahore and Kasur, but did not generate as much controversy and debate as Amritsar.

Public floggings and ‘crawling order’ were the rule of the day to be followed by arrests, bombing and firing at Gujranwala. “Floggings took place in public, and photographic records of these disgusting incidents are in existence, showing that the victims were stripped naked to the knees, tied to telegraph poles or triangles,” Horniman records.

Horniman’s power of the pen did not bend the British. But it fuelled India’s freedom movement under Mahatma Gandhi who issued a statement condemning British Raj’s treatment of the editor. “Mr Horniman is a very brave and generous Englishman”, said Gandhi. “He has given us the mantra of liberty, he has fearlessly exposed wrong wherever he has seen it and has thus been an ornament to the race to which he belongs, and rendered it a great service. Every Indian knows his services to India.”

Horniman notes that in Punjab, the oppression reached such a pitch that nowhere else than in Punjab, “the Defence of India Act, with its host of liberty-destroying regulations” was applied with such great intensity.

He rejected the government-constituted Hunter Committee’s one-sided report and called for a fresh probe. “After the revelations of the Hunter Committee, Great Britain cannot, if she is to maintain her honour before the world, remain quiescent… she will have to see whether the intention to terrorise the people of the Punjab was deliberate and prearranged.”

“British honour and good faith are gravely imperilled in India to-day. If the general character of our officials, civil and military, who are entrusted with dangerous powers in such countries as India, were such that outbreaks of terrorism of the kind we have seen in the Punjab are liable to occur at any time, we should be compelled to frankly abandon our claim to be a justice and humanity-loving people. However ugly the facts we must investigate and face them,” wrote Horniman.

The British treating India, the ‘Cinderella of the Empire’, would incite problems in other colonies, he warned. He fought, not just for the Punjab, but also for the farmers and workers in Bombay, political activists in Bengal and supported Madras-based Dr Annie Beasant’s Home Rule League.

He performed multiple tasks – of a journalist/ commentator, a participant and as an advocate of Gandhi’s Satyagraha, who explained to the Britons what it meant. He had a persuasive pen, filled with ink that smelt freedom, but not vitriol.

That he was a Briton, not part of the British imperialist system placed him in a class apart, a thorn in the rulers’ eye. It is difficult to find a parallel in independent India with his level of commitment to the cause, and readiness to suffer the consequences, including court cases and detention. For that matter, also commitment of the profit-making private media to genuine press freedom.

Horniman denounced the Defence of India Act and the Press Act used as tools by the British. Many of these laws have been retained in countries that were once part of British-ruled India. They have been updated and amended and presumably, made more stringent.

Of them, the sedition law taken notice of by the Supreme Court, is currently being debated in India. Read what Horniman had to say of the law then, and decide whether its essence has changed, no matter its current contexts and formulations.

He writes: “India is blessed with a law of sedition, which is as comprehensive and severe as one would have thought ingenuity could make it…. A seditious document is defined in the code as one which instigates, or is likely to instigate, the use of criminal force against the King, the Government, or a public servant or servants.

“Many historical works, reports of trials, or mere curiosities of literature might be brought within so vague a description and the innocent possessor of such, being unable to achieve the impossible and prove that he had no intention that they should be published or circulated, be penalised under the proposed section. They might even come into his possession as waste paper, and be used to wrap up tea or sugar with the most alarming results in the shape of a suggestion that he had discovered a peculiarly subtle and cunning way of spreading sedition,” he writes.

Horniman is one of the seven “rebels against the Raj” in historian Ramachandra Guha’s book. After essaying his life and work, Guha says of the present times: “When newspapers and television channels so routinely take the side of the state, when the government of the day resorts to internments without trial, the spreading of lies, and the promotion of sectarian bigotry, Indian journalists with a spine and a conscience can take inspiration from an editor who, as Gandhi himself put it, so “fearlessly exposed wrong wherever he has seen it”.

The writer can be reached at mahendraved07@gmail.com