How to promote ‘good’ cinema in a country that is the largest producer of films – over 2,000, annually – where viewing them remains the opium, next only to religion, of the masses?

Not very different from the rest of the world, the dilemma of India’s film society movement is having to struggle to stay relevant in radically changed times.

The Indian audiences are spoilt for choice with films being made in a dozen mother tongues if not more. By flocking to the cinema theatres to see anything they get, they seek to redefine what ‘good’ cinema is. Since film viewing is voluntary but compulsive, the approach is what-is-good-is-what-I-like and rejects what is not liked. The masses, as anywhere else, have remained untouched by the quest for good cinema of a few.

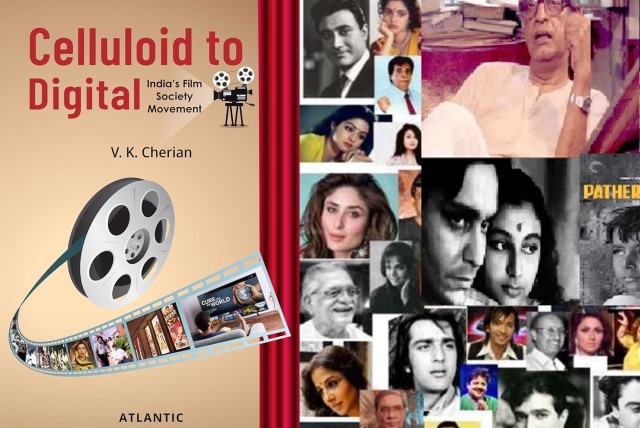

Besides being social, the change is also technological. A just-released book is aptly titled Celluloid to Digital. It seeks to explore the role of India’s film society movement in this century. It recommends change since the digital revolution has breached barriers. With OTT – over the top – platforms proliferating, film watching is no longer confined to cinema theatres. Nor is the cinema specific to a nation or a region. The book advocates a radical change in the outlook and the format to ensure that cinema appreciation remains alive and film societies do not become mere talking shops.

Penned by journalist and film enthusiast V K Cherian, the book, actually his third take on the subject, explores the movement of cine clubs/societies/associations/forums that began in Europe in the 1920s and spurred watching and discussion of niche cinema in India in the 1940s. It blossomed in the four decades after Independence.

Significantly, the movement coincided with what is called the Indian cinema’s “golden era” and with governments headed by Jawaharlal Nehru, Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi, all of whom patronised cinema as an art form and afforded it social respectability that it did not earlier have. The state influenced cinema’s growth by setting up the National Awards, the Film and Television Institute of India, the National Film Development Corporation (NFDC) and the National Film Archives of India (NFAI). Two inquiry bodies explored the workings of the cinema industry.

The movement ushered in a “cultural renaissance”. Among the pioneers were Satyajit Ray, Chidadanand Dasgupta, Ritwik Ghatak in Kolkata, Vijaya Mulye (akka) and Arun Roy Chowdhury in Patna and many marquee names in Delhi, Bombay, Bangalore, Trivandrum and other cities. It gave India some of its best films and filmmakers.

At Nehru’s instance, Marie Seton, “the chain-smoking, saree-clad British socialist” arrived in India. Cherian records that she was “truly the evangelist and the pioneer of India’s Film Society movement and contributed to the rise of the ‘new’ or ‘parallel’ cinema in the 1950s to the 1970s.

A worthy follow-up of the social change that India’s freedom movement ushered in, it gave among others Satyajit Ray and his Pather Panchali, Bimal Roy’s neo-realist cinema, Ritwik Ghatak who recorded the trauma of Bengal’s partition, Mrinal Sen’s comment on poverty and youth unrest and many in the South who interpreted social change. The ‘parallel’ cinema brought in the likes of Mani Kaul and Kumar Shahani. Actors included Naseeruddin Shah and Shabana Azmi who eventually switched to the commercial (desi) cinema. Shah later deprecated the “new wave” that abetted with time.

Significantly, the film society movement drew inspiration from the West even as India, unlike much of the world, resisted the Hollywood avalanche. Indian films – not ‘desi’ commercial potboilers but those who claimed a superior film language, marked their presence in many international film festivals.

In its heyday, the movement had a substantial following of film enthusiasts that grew to approximately 100,000 members by 1980. While it primarily attracted individuals who regarded themselves as devoted film enthusiasts, it gained momentum through discussions reminiscent of those that animated left-leaning cultural movements originating in late colonial India, especially the Indian People’s Theatre Movement (IPTA).

Four decades on, prominent filmmakers and film society members including Adoor Gopalakrishnan and Shyam Benegal, who have propagated the film society culture for decades, concede that it has remained confined to the urban educated and professionals who enjoy good cinema but have been unable to penetrate the larger society.

Perhaps, they did not try hard. Or, perhaps, too much was expected from an elitist movement that ran ‘parallel’ to the taste of the masses for whom cinema is little else but a source of entertainment. The other two purposes in a well-done film, imparting education and information, emphasised in the years after the Independence, have taken the back seat. This also explains the near-total emphasis on feature-length films as against a documentary.

ALSO READ: Bollywood Studios Fading Out

There has been some welcome streamlining by the government. But by and large, the state, while greedy about earning revenue from the cinema industry, is fast withdrawing from patronage and promotion that it earlier extended through funds and nurturing of institutions.

With or without state patronage and control, the cinema today impacts and is in turn impacted by an India that is fast urbanising and indeed, globalising. For one, rural India has more or less disappeared from the film narrative. The actors appear and act for a global audience. The niche Indian ethos is missing.

Today, the movement must live with many global cinema companies operating in the Indian market, financing and producing films. There is corporate financing, commercial viability, and better production values with the use of the latest in technology.

But two things any lover of good cinema will concede: India still produces more chaff than grain. And, it is difficult to make ‘great’ cinema like the opulent “Mughal-e-Azam” or ‘Devdas’, or a contemporary “Kaagaz Ke Phool” or ‘Guide’.

Part of the movement, Cherian says the only way for the film societies to survive is to become part of the media studies institutions at the university and college levels. They could capture the young by floating film clubs. As per the University Grants Commission (UGC), some 200 university-level institutions are already offering such facilities. Some of it is already happening in Kolkata and the South. This is practical since India is among the few major nations where media is growing and so are the media studies institutions. The Film Society movement is under dire stress even in Europe. India is better placed than France from where it imbibed the cinema and England from where the idea of the film society travelled in the 1920s.

Cherian wistfully writes: “India awaits a Pather Panchali,” taking a shot at another round of “cultural renaissance.” But he also wants the movement to confront the harsh reality: Does its ‘good’ cinema sell in this era of commercial blockbusters? “Bollywood’ and its southern allies-cum-competitors make billions at home, but also have a fast-growing global market. In a sense, the better of commercial cinema has raided the larder – the Western world from where ‘good’ cinema enthused and influenced many of India’s post-independence pioneers. It’s a small, complex world today.

For more details visit us: https://lokmarg.com/