The tiny Caribbean country, Cuba, is a speck compared to India. Its population of 11 million people is less than half of most Indian metropolises. Cuba struggles to remain afloat, its economy is restricted by US sanctions and revenues from tourism, a major source of income for the nation, has all but dried up since the Covid pandemic began in early 2020. But what is a curious surprise is how Cuba has managed to keep afloat in the wake of Covid. More than 90% of Cubans have been vaccinated with at least one dose of the vaccine; and 83% have been double-dosed. And this while many much larger and more powerful nations with stronger economies have struggled. The other remarkable fact is that Cuba has developed its own vaccines to administer to its citizens.

How did Cuba do it? In early 2020 when the pandemic’s first wave began gathering momentum, Cuba realised that it would need to act fast. Lack of resources and the sanctions imposed on it made it difficult for the nation to import vaccines at huge costs. So it got its own scientists to double up and develop vaccines. Those efforts bore fruit. Early this year, Cuba became the smallest country in the world to develop and manufacture its own vaccines.

Last year, the spread of Covid in Cuba was alarming with the small country reporting hundreds of deaths a week. But this year the story is different. Covid infections have plummeted and deaths are down to two or three a week. But the Cuban “miracle” is the result of something that the erstwhile head of the nation, the late Fidel Castro, had done decades ago. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Cuba invested heavily in biotech and healthcare, not only in creating pharmaceutical research facilities and hospitals but also in training doctors and other healthcare personnel. The result is a robust infrastructure that is paying back now.

Investing in healthcare is vital for developing countries but often it gets neglected. During the second wave of the pandemic, India’s lack of hospital infrastructure was in sharp focus as patients struggled to get hospital beds and oxygen.

As per the World Health Organisation’s data relating to Domestic General Government Health Expenditure (GGHE-D) as a percentage of GDP in the year 2018, India’s share of GGHE-D in GDP is 0.96%. That figure might have gone up marginally but it is still far lower than in many comparable countries. The lack of public health facilities takes a huge toll on India’s population and even in ordinary times patients have to depend on private medical facilities that are often expensive and poorly regulated.

In extraordinary times such as now, the problem is further exacerbated. Recent reports suggest during the third wave of the Covid pandemic, which is yet to reach the peak in India, there could be an acute shortage of healthcare staff. The nightmarish memories of seriously sick people gasping for oxygen or trying desperately to get hospital beds barely a year ago are still vivid. And the lessons from those experiences have to be learnt. For instance, the majority of Indians are not fully vaccinated (only 44% are, according to official estimates). The need of the hour is for India to accord top priority to healthcare infrastructure–be it through investment in hospitals, training of more healthcare professionals and research. If tiny nations such as Cuba can do it, why can’t India?

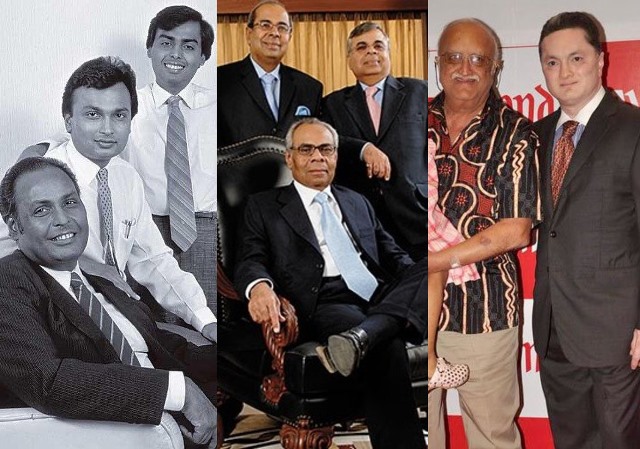

Is Reliance Readying For Succession?

Twenty years ago, after Dhirubhai Ambani died, a very public and acrimonious battle broke out between his two sons, Mukesh and Anil. It is widely acknowledged that the former emerged a victor from that spat. Today, Mukesh Ambani has grown his inherited Reliance empire into a US$217 billion empire, spanning oil refining and petrochemicals, telecom and retail, and he is one of the world’s richest businessmen.

Recently, he announced that the group was working on a succession plan. That should come as good news in corporate India. Mukesh who is 64 is still very much an active head of his diversified group but a succession plan at this juncture would be a prudent thing to embark upon. Part of the reason for the fight that he and his estranged brother had was because their father, Dhirubhai, had not clearly earmarked a succession plan. Mukesh has three children, twins Akash and Isha, 30, and Anant, 26.

‘Mukesh’s statement on succession has, predictably, led to speculation about how succession will be managed in the group. Will its businesses be split up and shared as inheritance for his children? Or will there be some other way of ensuring that the process happens smoothly. One theory doing the rounds is that perhaps the plan would be not to split the businesses, given that each of them have a different set of risks and future potential. For instance, in the long run, refining and petroleum could become a sunset industry given the move away from fossil fuels. On the other hand, Reliance’s telecom business is seen to have a brighter future both in India and globally.

Many believe that the next move by Reliance could be to set up a family trust and bring the flagship company Reliance Industries under it. The trust’s board could have as members, Mukesh himself, his wife Nita, and his three children. That could ensure that the businesses remained under family control and minimise intra-family discord. The coming months would probably reveal what really will be the succession plan at Reliance but corporate India will be eagerly waiting to see how it unfolds.