What can one say about a film that took 16 years to make, its genre no longer popular when released, and its main attraction looking jaded, only a sad reminder of her resplendent beauty?

Well, you can say that despite these and numerous other debilities, it remains a classic that has grown with time. Fifty years after its release, Pakeezah (The Pure) continues to be viewed and debated by the discerning in the new century.

India was in a triumphant mood after the 1971 war when Pakeezah was released on February 2, 1972. People had no stomach for its deep melancholia. Romantic and opulent historical and “Muslim socials” of 1950s-60s (with notable exceptions Shatranj Ke Khiladi-1977, Junoon-1979 and Umrao Jaan-1981) were yielding place to contemporary themes. The “angry young man” was knocking at the cinema door.

After many expensive fits and starts, writer-director Kamal Amrohi barely managed to complete filming Meena Kumari, his estranged wife and muse. Both knew she was dying. Despite its rich artistic content and popular songs, Pakeezah flopped commercially. It marked the end of a life-time dream. Until…

Re-released after Meena Kumari died, just eight weeks later, on March 31, it stormed the cinema theatres. Not only were the fortunes revived and the fame restored, Pakeezah and Mena Kumari became synonymous. They overshadow her earlier acting triumphs and for that matter, also Amrohi’s outstanding films, with and without her.

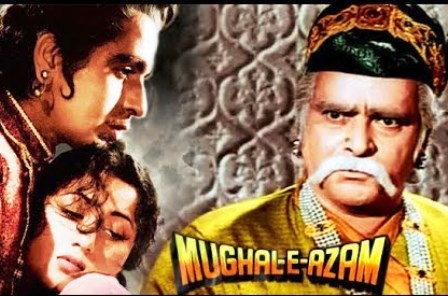

Although it loses out in most departments except in music, Pakeezah often gets compared with Mughal-e-Azam (1960), a magnificent story of another bygone era, arguably one of the greatest films ever made in India.

ALSO READ: Unparalleled Reign Of Mughal e Azam

Many stories, real, apocryphal, even autobiographical, fuelled the making of both the films. Amrohi, appointed as one of the four writers for Mughal-e-Azam, abandoned Pakezaah because both had similar themes drawn from the Anarkali legend. Separated for five years from wife, he considered replacement. But he couldn’t imagine Pakeezah without Meena Kumari, and gave up again. Friends Nargis and Sunil Dutt helped their patch-up.

To lighten his burden, Amrohi engaged Satyen Bose, but couldn’t quit direction. Signing writers Akhtar-ul-Iman and Madhusudan led to disputes. He had to pay a fine to disengage with the latter. So, no Pakeezah without Amrohi as well.

The film’s German cinematographer, Joseph Wirsching, died in 1967. Technology switch was needed from Black & White to Eastmancolor. Composer Ghulam Mohammad died, requiring Naushad to complete the soundtrack, finally ‘arranged’ by Kersi Lord.

Pakeezah is the story of a tawaif, a courtesan. Unable to marry her lover Shahabuddin, she begets a girl-child before dying. Her sister Nawabjaan raises the child, grooms her as a dancer. The love story repeats, this time between Sahibjaan and Salim, a forest officer, also a nephew of Shahabuddin.

Family patriarch, common to both situations, rejects Sahibjaan. He shoots Shahabuddin who, shamed by Nawabjaan, wants to redeem himself. After this blood-letting, Salim has his way. He marries Sahibjaan, his Pakeezah. A poignant ending with justice, a rarity, for a courtesan.

Thanks to frustrating time-loss in production, Ashok Kumar, signed to play Salim, grown old, had to play Shahbuddin. From ‘stars’ of the day — Dharmendra, Raaj Kumar, Rajendra Kumar, Sunil Dutt, and Pradeep Kumar – Amrohi chose Dharmendra as Salim. But well into shooting, he found the wife getting on “too well” with Dharmendra, enough to distract filming. There were rumours galore. The possessive husband-director dropped Dharmendra.

It was finally Raaj Kumar. He sees Sahibjaan sleeping on a moving train. Smitten, he leaves a note between her foot thumb and finger: “Aapke paon dekhe, bahut haseen hain. Inhein zameen par mat utariyega… maile ho jaayenge” (Your feet are really beautiful. Do not step on the ground… lest they be soiled). The dialogue is rated as one of the most romantic/erotic scenes in Indian cinema.

When released, the courtesan culture, the kothas of Lucknow et al, were passé. Not that there was no room for romanticism. But India was ready for another theme, Garam Hawa (Hot Winds-1973), about the plight of a Muslim businessman and his family, in the aftermath of the 1947 Partition. Only a year separated it from Pakeezah.

However, these “hot winds” couldn’t dampen the romance of Pakeezah and its songs. They also blew across the border from an aspiring India to a just-truncated Pakistan. Thankfully, Pakeezah helped a catharsis between the neighbours.

End-1972, I witnessed an India-Pakistan border “flag meeting”. A Pakistan Army officer, with roots in India’s Moradabad, half-seriously urged his Indian counterparts tasked to remove the explosives on the minefield, to “leave one mine only to be cleared by me, with a gramophone record of Pakeezah songs concealed underneath”.

India’s Doordarshan telecast Pakeezah from its Amritsar centre on September 29, 1973. Columnist Ibn-e-Imroze wrote in Daily Imroze: “The day Pakeezah was televised, Lahore cinemas wore a deserted look. Black-marketers sold their tickets even below the face value. Lahorewallahs had resisted (India’s) 1965 and 1971 attacks, but surrendered to this invasion of 1973. People invaded TV shops. Those who could not get one, fixed bamboo antennae on the roofs of their houses (to watch direct telecast), to console their frustrated feelings. Traffic came to a halt, pockets were picked, even doctors said to their patients: ‘If you remain alive till then, I’ll see you tomorrow. Today I am going to see Pakeezah’.”

To anyone with an ear for music, the film’s pull is undeniable. Among those gems, alas, Inhin Logon Ne seems plagiarised. It can be heard on Youtube in Shamshad Begum’s voice, sung for a 1941 film Himmat. The lyric is by Aziz.

Film analyst Gautam Kaul writes: Majrooh Sultanpuri had stolen the lyric from Aziz for Ghulam Mohammed, a contemporary of Pandit Gobind Ram, the original composer from the Lahore School.

Cut to 1972. Kaul notes: “It is the same kotha, the same assembly of men, the same musical score, the same song, the same Kathak style, but it is Technicolour, and a bloated Meena Kumari, with leathered skin due to constant drinking, is attempting to dance. The dancing isn’t a patch on the rendition by the light-footed young actress Manorama in the original.”

Truth be told, Meena Kumari was too sick to dance. She was filmed sitting. Padma Khanna performed all her dance movements, not credited to any choreographer.

None of these prevented the film’s earning five times the sum spent on production. Its soundtracks sold the best across Asia and topped the popularity charts of Radio Ceylon’s Binaca Geetmala, then a decisive benchmark.

Chalte Chalte, “Aaj hum apni duaon ka asar and Thaade rahiyo, for which she designed the costumes, remain the most memorable song-and-dance performances. A storm of protests from the film fraternity damned Filmfare that denied awards to Pakeezah because its leading contenders were dead.

In 2005, the British academic Rachel Dwyer called Mena Kumari’s character a “quintessentially romantic figure: a beautiful but tragic woman, who pours out her grief for the love she is denied in tears, poetry and dance.”

Meena Kumari’s fee for acting in Pakeezah was one sovereign gold coin. Kamal Amrohi gave that to his dying wife. She clutched it till she passed away, never able to see it or the released film. Pakeezah was truly, Meena Kumari’s film.

The writer can be reached at mahendraved07@gmail.com