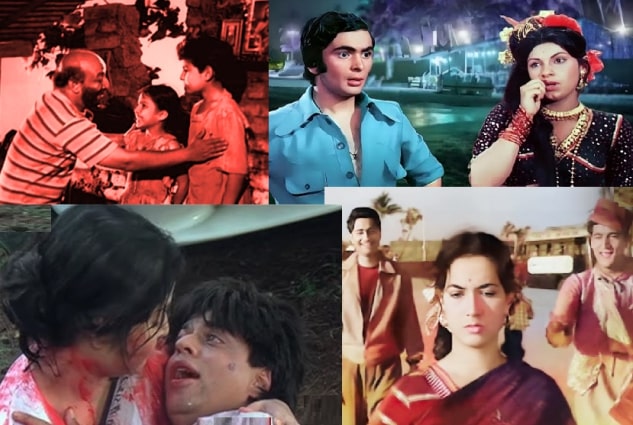

A common point between Raj Kapoor’s Boot Polish (1954), Guru Dutt’s CID (1956) starring Dev Anand, Shah Rukh Khan’s Baazigar (1993), Irfan-starrer Lunch Box (2013) and Bambai Meri Jaan (2023, Amazon Prime Series), besides being made across seven decades, is that they were shot outdoors on a group of picturesque islands on the Arabian Sea.

Madh Island, beyond the sea-facing view, offers not just scenic beauty but also the authentic culture of the Koli fisherfolk who are the original residents of Bombay, now Mumbai, which was itself built linking seven larger islands.

The Konkani-Marathi culture of colourful fisherfolk, with their sturdy, bejewelled women sporting full-sleeve blouses and nine-yard (nav-vari) saris, has so far resisted change, but their homes, essentially bamboo shacks, are yielding to swank bungalows, many of them becoming film studios.

Some 49 of them are thriving, within Mumbai’s civic limits, but far away from the madding crowds and traffic jams of the congested megapolis.

Last century’s records say that Madh and its surroundings began as outdoor shooting sites as far back as the 1940s. Away from the confines of the studios, outdoor shoots began there, along with Ghodbunder Road, Aarey and a few locations that offered open space uncluttered by crowds of film-crazy onlookers. For Bollywood, the important thing was that they were within the city or its outskirts, and nearby, saving travel time and cost.

Madh became hugely popular after Raj Kapoor’s Bobby (1973), which launched Rishi Kapoor and Dimple Kapadia. In a song sequence, Rishi visits a fishermen’s village at Dana Pani beach to woo Dimple, and the two dance to the supposedly Konkani tune (the taal and chorus refrain mimic traditional Koli folk music), singing the famous ‘Ghe ghe re ghe re, ghe re sahiba’ song. With that fame, Madh lost its serene solitude, so far attuned only to the sea waves.

Yet, for an island virtually off Mumbai, Madh was, and remains, difficult to access. The shortest route is through a polluted creek from Versova jetty, which requires a three-minute ferry ride. The other route is a 20 km detour via land that houses Navy and Air Force establishments, through a single road that, now heavily traversed, needs constant repair.

Bollywood has thronged the island because it provides an alternative to the studios in the city, many of which have closed down in recent years. The Film City complex is considered expensive and is strictly regulated by government-imposed rules and procedures. Many filmmakers say that only the big production houses can afford it.

Without a formal name, the cluster of studios at Madh offers space and facilities for rent ranging from ₹15,000 to ₹200,000 per day. Many of them are bungalows or complexes. Imaginatively designed, they have been a lucrative investment for ‘stars’, retired and current.

ALSO READ: Why Khan Market Is Losing Business?

Pass through these surroundings in the evenings, and you notice rows of limousines, buses that ferry a huge supporting workforce from the city and diesel-fuelled power generators with unending cables – all on a narrow street. Arc-lights inside and the bustle outside indicate that ‘action’ is on for a film, TV serial, ad clip or what eventually hits the OTTs – over-the-top entertainment.

Although apprehensive about the change this influx has brought, the locals of Madh are non-interfering. They are a mix of Hindu, Muslim and Christian, co-existing for a long time. The “ghe ghe re sahiba” culture dominates.

Compared to Mumbai, the real estate, so far, is relatively cheap. While Bollywood’s biggies reside at Juhu, Khar or Bandra, the up-and-coming ones have made their homes on both sides of the creek. With work virtually next door, they cut on travelling time.

You may run into Pankaj Tripathi or Sharat Saxena or once-wildly popular Rahul Roy. Or actor-director Tinnu Anand rushing down the jetty to join other passengers – students, workers, office-goers, fisherfolk – on the motor-driven launch. Within minutes, they reach the ‘mainland’ to negotiate the crowded city.

Actor Shakti Kapoor has a home named after his now-famous daughter, ‘Shraddha Nivas’, at a location called Patilwadi. Actor and TV personality Archana Puran Singh and her actor husband, Parmeet Sethi, have a property that features a large, beautiful garden and is made up of two bungalows. Indeed, the opening of their new home became an ‘event’ in typical Bollywood fashion, with choreographer-director Farah Khan visiting it, cameras in tow, to admire the home’s ambience, especially the interiors.

Pankaj Tripathi has a sea-facing home designed with a rustic, traditional Indian village ambience. It is named ‘Roop Katha’. The island also has the late Irrfan Khan’s former residence.

There can be bad news, but then, it is news. A portion of Mithun Chakravarty’s home was demolished recently. Some years back, an aspiring starlet had a public spat with director Madhur Bhandarkar. Or, during the Covid-19 pandemic, when everything was supposedly shut down, the police discovered alleged porn film shooting.

Several of these studios have faced scrutiny regarding their legality. In September 2022, the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) initiated an inquiry into these studios, focusing on their compliance with zoning regulations concerning the No-Development Zone (NDZ) and Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ). Following this investigation, in March 2023, the BMC commenced the demolition of five studios that were found to be operating without proper permissions.

Madh is, nevertheless, the Mini Bollywood. Its less-cluttered beaches at Aksa, Dana Pani and Erangal have wide space along the seashore, where structures allow for make-shift innovation. It has diverse locations, from beach resorts to rural landscapes, perfect for a variety of film genres. A Portuguese-era fort provides a backdrop for much action. The quaint houses in narrow lanes allow for ‘filmy’ action.

The aspiring youngsters from the island and around find work, hoping to get ‘creative’ someday. Many entertainment-related offices, like casting agencies, have come up. The weather is typically “Bombay-like”. The coastal climate, especially during monsoons, can sometimes disrupt schedules.

Amitabh Bachchan began his career shooting some scenes for KA Abbas’ Saat Hindustani (1969). Years later, he shot Mard (1985). Akshay Kumar shot Phir Hera Pheri (2006) and Lakshmi Bomb (2017). Ajay Devgn’s Singham Returns (2014) was shot here, and so were Crime Patrol, Savdhan India, CID, among other TV shows.

The island offers relative safety, besides crime, from wild animals. Traditionally known for beaches such as Aksa, Dana Paani, Bhati, Silver Beach, it also has an old 16th-century Portuguese Church – St. Bonaventure.

The Madh environment offers a heady mix of film, finance and fishing, a major reason why Bollywood has not moved, and is unlikely to move, to any other place in the country.