The Chinese President Xi Jinping launched the BRI with much fanfare and high promises and grandiose plans for the participating countries in 2013. It was considered to be a centrepiece of the Chinese foreign and trade policy.

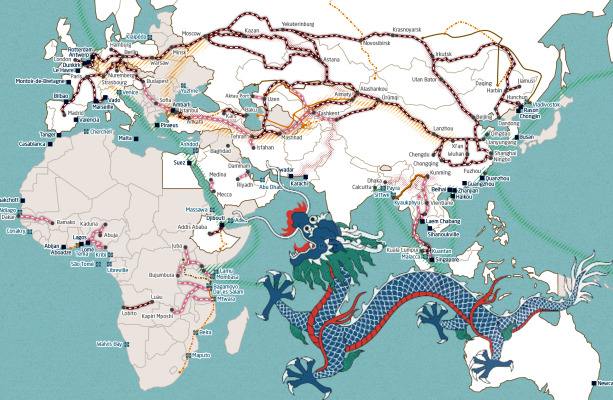

Basically, Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) earlier also referred to, as One Belt One Road or OBOR for short, is a global infrastructure development strategy to invest in nearly 150 countries and international organisations, around the globe.

The BRI formed a central component of Xi’s “Major Country Diplomacy” strategy, which calls for China to assume a greater leadership role for global affairs in accordance with its rising power and status. As of August 2022, 149 countries were listed as having signed up to the BRI.

Xi originally announced the strategy as the “Silk Road Economic Belt” during an official visit to Kazakhstan in September 2013, referring to the proposed overland routes for road and rail transportation through landlocked Central Asia along the famed historical trade routes of the Western Regions; in addition to the “21st Century Maritime Silk Road”, referring to the Indo-Pacific sea routes through Southeast Asia to South Asia, the Middle East and Africa. In fact the BRI was also considered a grandiose plan to challenge the American hegemony over the global trade and diplomacy.

However, the recent events in Sri Lanka, with similar echoes being heard from Bangladesh, Nepal and Pakistan has led some China watchers to conclude that this is an indicator of the hit that the Chinese economy has taken during the Covid pandemic and the BRI appears to be under revaluation with recipient countries wary of the debt trap and its economic feasibility.

Let’s take a closer look at the original intent of the BRI, its expansion and its long and short-term impacts on the aid recipient countries and whether it has been a success or a failure and how the U.S. could have countered it in a much better manner.

In his report in 2020, Rafiq Dossani, Director, RAND Centre for Asia Pacific Policy opined that China’s strongest motive behind the BRI was its long-term economic security. The maritime routes of the BRI would have helped the relatively underdeveloped, landlocked areas of China such as Yunnan and Xinjiang provinces by linking them with ports in the more rapidly growing areas of Asia.

At the same time, the emerging land routes of the BRI were marked as an alternative to the South China Sea, through which most of China’s trade currently passes and which is becoming a zone of contestation between the United States and China.

Dossani further explaining the reasons for the initial welcome of BRI opined that traditionally, many countries prefer to work with the World Bank and other multilateral lenders, which provide borrowers with good practices, while making significant funding available on a meritocratic rather than political basis.

But, he says further that from a developing country’s viewpoint, accessing the world’s spare capital has been difficult because of the risk entailed in many such investments. The Asian Development Bank estimates that Asian countries face an infrastructure investment gap of $459 billion a year.

This logic also explains the sentiments, which in the initial stages of the launch of the BRI seemed to be the main attractive reason for the BRI projects and Chinese funding. But nine years after its launch BRI seems to have lost its sheen, due to the economic meltdown in several countries, which borrowed heavily from China under the garb of infrastructure development, progress and prosperity.

Bangladesh Finance Minster AHM Mustafa Kamal has publicly blamed economically unviable Chinese BRI projects for exacerbating economic crisis in Sri Lanka. He says that developing countries must think twice about taking more loans through BRI as global inflation and slowing growth add to the strains on indebted emerging markets.

In fact Bangladesh has made it clear that it will not accept any further loans but only grants from Beijing. Nepal has also taken the same stand. Pakistan with some US $ 53 billion being spent by Beijing under the aegis of BRI also faces the same fate.

China has also invested some US $ 44 billion in Indonesia, US $ 41 billion in Singapore, US $ 39 billion in Russia, US $ 33 billion in Saudi Arabia and US $ 30 billion in Malaysia.

The cry against Chinese BRI is not limited only to Indian sub-continent as its reverberations can be heard in the stalled US $ 4.7 billion railway project in Kenya, also. Five years since its launch, the project ends abruptly in an empty field, 200 miles from its destination in Uganda.

As conflicts between the United States and China appear to mount, some experts have questioned the intentions of China’s BRI. It has been viewed as a debt trap for impoverished states and a means for China to expand its territorial control, but is it a reality? Is the United States missing an opportunity to participate-in or initiate parallel activities?

BRI has been repeatedly labelled a debt trap and a power grab, and perhaps this seemed like a possible scenario. However, this concept has been debunked by recent research. Deborah Brautigam, director of the China Africa Research Initiative at Johns Hopkins University, found no evidence that Chinese banks over-lend or invest in loss-making projects to obtain a foothold in those countries, in one of her studies on Chinese lending to Africa.

There is further evidence that China is not engaging in debt trap diplomacy. Brautigam has noted that in some countries the IMF has been labelled as being vulnerable. Also Chinese loans were not responsible for pushing indebted countries above IMF debt sustainability limits.

Furthermore, it should be noted that not just impoverished nations, but East Asian and Europe countries have also been smitten by the BRI. Over 18 European Union countries have joined the BRI.

In fact, rather than decrying China, the United States should engage in infrastructure lending to poor countries, and/or make it easier for multilateral banks to lend for such projects, reducing bureaucratic requirements. It should also initiate similar activities in under-developed or developing countries.

To better its image, China should improve transparency around BRI deals. The World Bank and other bodies have also called for increased transparency. This would go a long way in improving U.S. and other countries’ understanding of Chinese intentions about the BRI.