Whatever success is claimed by the Delhi Summit of G20 countries under the presidency of India, the absence of Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin from the conclave of leaders even while they were represented by their prime minister and foreign minister, respectively, robbed the meeting of some glitz.

Putin has been extremely circumspect with foreign travel since the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued a warrant for his arrest on alleged war crimes in March. Though India like the US is not part of ICC, Putin must have believed that his presence in Delhi would invite smirks from many attendees. Then he has preoccupation with the challenges that the Ukrainian war has thrown up and internal dissensions. Xi had quite a few considerations to avoid being in the summit, for he knew that with the support of the West, the summit would herald an ambitious infrastructure project touching many countries amounting to a challenge of China’s own Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

While many saw Xi’s absence as a snub to the G20 summit, Prime Minister Li Qiang who joined the party instead played, to every other participating country’s relief, a role that didn’t leave a room for dissonance. In the meantime, Xi is continuing with subtle that finally would amount to something profound changes in diplomacy aimed at seeking leadership of the global South. At the recent BRICS meet in South Africa’s Johannesburg, Xi had reasons to celebrate that Saudi Arabia and Iran in whose reconciliation Beijing had an important role were inducted as two of the six new members.

At the same time, it is to be said to the credit of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi that he is making an outreach to the Islamic world and this has come for praise from none other than Congress Working Committee member Shashi Tharoor. It was largely at the instance of Modi that the African Union representing 55 countries was inducted as a new member of G20.

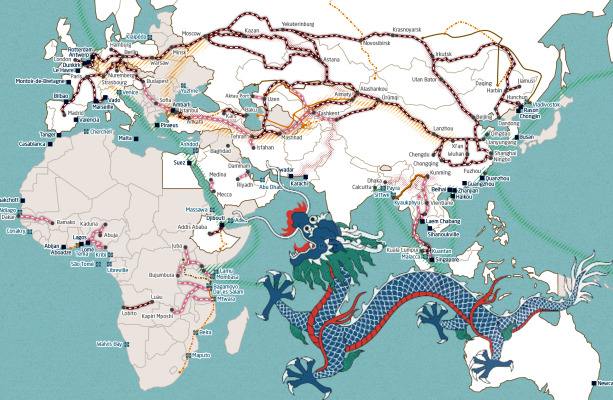

India has good relations with all the new BRICS inductees. But for Beijing BRI is an important handle to have the global South on its side in the influence war with the West, the US in particular. Launched ten years ago, BRI that revived vision of Chinese attempts to revive the Silk Road is seen as Xi’s signature foreign policy initiative. Since its launch, China’s cumulative BRI engagement amounts to over $1 trillion, with nearly $596 billion in construction and $420 billion in non-financial investments.

Even while many flaws have been identified in project selection and execution and governance resulting in many project and aid receiving developing countries now tittering on the brink of default, BRI finance and investments are once again picking up. A report by think tank Green Finance and Development Center says in the first half of the current year, over 103 BRI deals worth $43.3 billion were done compared with approvals claiming investment of $35 billion in six months to June 2022.

This is proof that though Xi is aware of the factors telling on many BRI projects such as bending of rules by Chinese banks while financing projects in unstable countries marked by human rights violations, rigged elections and fratricidal warfare, he will not allow atrophying of the programme. At the same time, he wants the projects to pay for themselves. Times have changed since the unveiling of BRI. The country’s economic performance continues to disappoint, the economy having grown at an annualised rate of 3.2 per cent in the second quarter. China grew by only 3 per cent in 2022.

ALSO READ: China And West – A Poisoned Relationship

According to a survey of 37 economists by Nikkei, the Chinese GDP growth counting average opinion will be 4.7 percent this year, but with many putting it still lower at 4.0 per cent. Beijing is greatly concerned that the country’s exports took a year on year dive of 8.8 per cent in August, the fourth month in a row of decline. Property developers continue to be haunted by payment defaults to banks and the economy is facing deflationary risk unlike the Western countries and India where inflation continues to remain a major concern.

As China remains in search of economic recovery, citizens keep on wondering why Beijing should remain the world’s largest creditor to developing countries supporting their infrastructure development instead of announcing a big bang fiscal stimulus package to fix its own faltering economy. But for China there is no backtracking on BRI, for it will now be engaged in a contest with India inspired India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEE-EC) project accepted at New Delhi G20 summit. Earlier, sensing that they are missing out on the goodwill of low and middle income countries where China’s presence is increasingly felt, advanced economies represented in G-7 have too proposed an investment of $600 billion in infrastructure development of poorer regions. But nothing concrete has happened as yet.

Facing such challenges, Xi wants cleaning up BRI related accounts without, however, going for a haircut. Earlier dodgy lending practices are shunned and funds siphoning by politician-bureaucrat nexus at aid receiving countries are largely plugged. Beijing has given a clear message that henceforward projects will be chosen based on their viability and a fair return. The Economist says Chinese President wants investors to focus on “small but beautiful” projects with promise of good returns, effective governance and oversight not to allow fund misuse. While funding of infrastructure that poor and developing nations need more than anything else, Beijing now is also talking of a digital silk road through the global south enabling it to participate in world digitalisation.

Arguably, IMEE-EC is the single most important breakthrough at the G20 summit, which if funded properly will prove to be a significant booster of trade encompassing India, the Middle East and Europe. Multi-modal connectivity of the three continents is a much discussed idea. The challenge is in getting all the countries on board and arranging funds. What, however, is to be accepted that in scope and the number of countries to be covered, IMEE-EC will not stand in comparison with BRI.

Xi must be patting himself on the back that over 150 countries touching all geographies and home to nearly 75 per cent of the world population and accounting for half the global GDP are part of BRI initiative. Come October, China will be hosting the third BRI forum in its capital city where it is expecting attendance of more than 90 countries. Interestingly, President Putin will make his first trip abroad since the issue of arrest warrant by ICC to attend the Beijing meeting.

Ahead of the BRI meeting, Xi is hosting Zambian President Hakainde Hichilema and Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro. BRI is no charity. China is carefully choosing the countries rich in minerals and crude oil and gas but short of resources to build infrastructure. Thereby it is earning goodwill. Some years preceding the launch of BRI, China became a key lender to Venezuela in 2007 providing funds for infrastructure and oil projects. In the next phase of development of its oil industry, Maduro will need more foreign funding. He has described his visit to China as historic since this is happening after years of frosty relations with the BRI promoter. In the meantime, the US is seeking engagement with Venezuelan officials after lifting of sanctions. But this will be conditional on Maduro making a promise of fair elections to be held next year.

While this being so, Beijing is not in the habit of raising issues of human rights violation and absence of democracy in its engagement with aid receiving countries. Incidentally, President Biden while in Delhi for the G20 summit made it a point to raise the “importance of respecting human rights” with the Indian prime minister. Biden told reporters in Hanoi: “As I always do, I raised the importance of respecting human rights and the vital role the civil society and a free Press have in building a strong and prosperous country with Biden.” If this is the kind of US engagement with the world’s largest democracy, then it does not leave to one’s imagination what Washington will be demanding of Venezuela for lifting sanctions. No wonder Beijing has an edge in dealing with regimes, which are not bound by democratic norms.

China is the world’s largest importer of oil and despite US sanctions, Beijing is importing crude – mostly heavy sour Merey and Boscan – from Venezuela. The South American country with proved reserves of 304 billion barrels are ahead of Saudi Arabia’s 298 billion barrels. Naturally China will be keen to have normal relations with Venezuela likely resulting it investing in development of oilfields and related infrastructure. Repairing relationship with China will help Maduro in his bid for third presidential terms as he is to derive political and economic benefits from rivalries between the world’s two largest economies. It will be recalled that Beijing was a major lender to Venezuela in 2007 when the country under the leadership of Hugo Chavez was engaged in developing its oil industry and infrastructure.