Nearly a century and a half ago, a renowned English tea expert J. Berry White wrote tea “has the reputation of furnishing a beverage that cheers but does not inebriate.” White at the same time described “tea mania as an addiction.” This addiction was not confined to the ones for whom tea drinking became a religion. Enthusiasm to grow tea for many decades since then became so infectious that Robert Fortune, whose reputation is based on expanding tea cultivation here using seeds smuggled from China lamented that “in India every man seems to think himself qualified to undertake the management of tea cultivation without having any knowledge of the subject.”

Fast forward to the present times. Is not the unchecked wilting of tea industry in Darjeeling, very small in size seen in the context of India making 1,365 million kg in 2022 but commanding an unrivalled reputation for quality, over the past many decades also largely due to poor estate management? What Fortune feared would befall tea industry in general so long in the past if gardens come to be managed by unschooled owners is proving right for gardens in the hills of Darjeeling. Tea being the principal source of revenue and livelihood for Darjeeling, the unchecked setback in its fortunes has been wreaking havoc on the local economy as it is also a cause of social unrest.

In more than one way, the past year would go down in the annals of the famed Darjeeling tea industry abroad as annus horribilis. Production of tea in the hills slid a worryingly around 9 per cent to about 6.3 million kg in 2023. The exact production fall will be known when December plucking and manufacture figures are available. In any case, the cold December when flushing of tea leaves don’t happen is a marginal month in terms of plucking. Quality of the hill origin beverage that begins to turn indifferent at the end of the second flush with the onset of monsoon turns even flatter during the year-end. December neither contributes of any significance to revenue nor to profits with harvesting limited to around 60,000 kg and quality not in line with the hill produce in preceding months. That tea does not find favour in the export market and is almost all sold locally.

The unique beverage of Darjeeling origin and of the first two flushes continues to enchant royalties from the United Kingdom to Japan and connoisseurs with deep pocket across the globe. Select ranges of first flush Darjeeling tea will fetch eye-popping prices from European and Japanese buyers in spite of their economies not having the best of times. But as is the long-time global experience, very high value products from Hermes bag to Bugatti and Rolls Royce cars to Patek Philippe and Berguet watches will do well through all economic seasons. People with astronomical income is spared tightening the belt when the general economy faces headwind. Some lines of Darjeeling first flush harvested in small quantities making them rare and highly coveted would fetch prices of around $300 a kg. The first flush beginning in February and finishing in April with new two leaves and a bud will leave a light, floral, fresh, brisk and astringent flavour in the brew. A divine experience for the few who can afford.

Incidentally, Darjeeling tea was the first among all commodities in India to have been accorded GI (Geographical Indication) status. Securing this recognition following multi-steps scrutiny became essential as large volumes of teas of other origins with some attributes of Darjeeling tea but not in any way comparable in quality with what is produced in the hills of north Bengal were sold in the market here and abroad as Darjeeling tea to the dismay of its makers. Such fakery not only did damage to the brand value of Darjeeling tea but also told on producer margins.

The Tea Board, the administering authority of GI, says the regulations apply to “87 tea gardens” whose harvested leaves have been “processed and manufactured in a factory located in the defined geographic area” and when such tea subject to review by tea tasters is found to have the “distinctive and naturally occurring organoleptic characteristics of taste, aroma and mouth feel, typical of tea cultivated, grown and produced in the region of Darjeeling, India.” The requirement that only 100 per cent Darjeeling tea is entitled to carry the Darjeeling logo has to a large extent succeeded in stamping out teas of other origins being masqueraded and sold as Darjeeling tea.

ALSO READ: Storm Brewing In Darjeeling Teacup

Even then in the domestic market, practically unrestricted arrival of tea from Nepal across the border continues to play spoilsport for Darjeeling tea, especially by way of depressing prices. While large imports from Nepal continue to cause distress to tea producers in Darjeeling, a very few gardens in the hills are in the black, unable to recover production cost, not to speak of earning profits, from auction and private sales. No wonder, as many as ten gardens in Darjeeling remained closed through 2023, knocking off around 1 million kg of production.

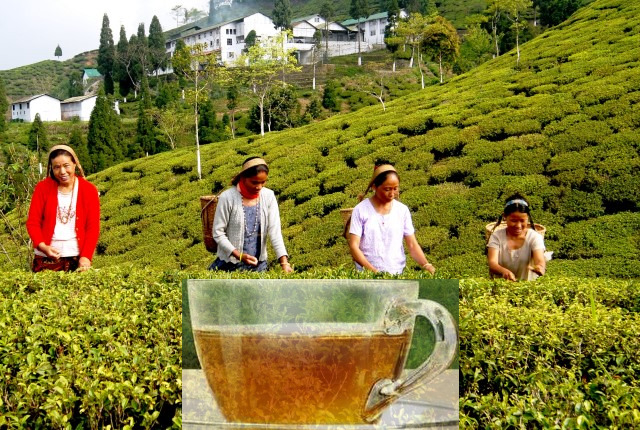

But the industry ills go well beyond that. Leave out a little over a dozen estates, the owners of other operational gardens are desperate to exit the business, only if they would find buyers. The figure of ₹200 a kg loss borne by Darjeeling gardens may be an overstatement by Indian Tea Association. The depth of the crisis is, however, not to be denied. For mitigation, the industry is seeking subvention from the state government on two counts – promotion of exports and transport subsidy. Even while West Bengal government’s financial health remains a subject of concern, it cannot but lend a patient hearing to Darjeeling planters, providing livelihood to nearly one lakh people with women engaged in plucking benefiting in a major way.

The unique climatic condition, cool bridge from the Himalayas wafting through the gardens in the hills, which are brushed by thick clouds, soft mountain rains and intensive sunshine help in making that adorable beverage. The rich organic reddish soil is also a deciding factor in making Darjeeling tea the ‘champagne among all teas.’ A planter of nearly five decade standing says the magical properties of Darjeeling brew has got much to do with estates being at high elevation of 600 to 2,000 metre above the sea level. The higher an estate is located in the hills, the better is the quality of its tea.

Whatever the mystique surrounding the tea grown in the southern slopes of the Himalayas covering an area of 17,500 hectares, the crisis surrounding the industry is worsening. Darjeeling tea continues to experience a downhill journey from the time when production would be over 10 million kg, with the withering of a good number of gardens and some experiencing ownership change. When committed planters of the kind of Rudra Chatterjee of Luxmi Tea or Ashok Lohia of Chamong Group will step into a weak estate, the working inevitably improves over time. Goodricke Group is also doing a good job in increasingly difficult circumstances. But all that is not enough to redeem plantation in Darjeeling hills wherefrom tea in 2023 auctions at Rs319.74 a kg sank to its lowest since 2015 when it was a distressingly low Rs285.71 a kg.

Not even a quarter of Darjeeling tea output is sold through auctions, allowing scientific price discovery. Whatever that is, fall in auction prices combined with geo-political crisis involving two raging conflicts involving Russia-Ukraine and Palestinians-Israelis ensured up to 20 per cent erosion in private sale prices over 2022. Calcutta Tea Traders Association secretary J Kalyana Sundaram would attribute the setback in auction and private sale prices to export demand squeeze and the continuing impact of imports of Nepal origin tea on domestic sale of Darjeeling tea. Annual exports of Darjeeling, made up of a very large portion of the first flush and a fairly good amount of second flush, are around 3 million kg.

Much to the concern of planters in Darjeeling, imports from Nepal had a humongous share of 17.36 million kg in total arrivals of 29.84 million kg here from all destinations in 2022. The industry has recommended to the central government some corrective steps to curb imports from Nepal. The more important of these are: fixing of a minimum import price for tea originating in the Himalayan neighbour and subject all imports to quality testing to ensure that foreign origin teas, Nepal and otherwise conform to standards of the Food Safety & Standard Authority of India (FSSAI). Whatever the industry may want, it will do well to remember that New Delhi will not be inclined to initiate any steps that may cause misunderstanding in Kathmandu.