Last week, Israel accused four freelance Gaza-based journalists who have worked with Western media outlets of having advance knowledge of the Hamas attack on October 7, which triggered the ongoing bloody conflict in Gaza. The journalists, mainly photographers, were accused of collaborating with Reuters, Associated Press, CNN, and the New York Times, all of them media outlets of considerable repute.

The accusation, made by Israeli communications minister Shlomo Karhi, was based on a report by a pro-Israeli media watchdog group, Honest Reporting, which stated that the journalists and, therefore, the organisations they were working for had prior knowledge of the horrific attacks by Hamas. In the past also, Honest Reporting has accused newspapers such as the New York Times and other western publications of an anti-Israel bias in their coverage of the conflict between Israel and Palestine.

The accusations have serious implications. In the October 7 attack, 1,200 Israelis died and more than 240 were taken hostage. It has led to a bloody battle with Israel seeking retribution by launching a full-scale attack against Hamas but the collateral damage from which has killed, displaced or injured thousands of civilians.

On their part, the four media outlets—Reuters, AP, CNN, and the New York Times—have denied any prior knowledge of the attacks. They emphasised that there were no arrangements in advance with the journalists to provide photos. The New York Times described the accusations as “untrue and outrageous,” highlighting the risk such unsupported claims pose to journalists on the ground in Israel and Gaza.

Covering wars such as the one that is ongoing in Gaza or the one that is raging for nearly two years in Ukraine after Russia attacked the country in February 2022 is fraught with risks. Of course, the primary risks that journalists face are obvious: the possibility of getting caught in the attacks, suffering injuries, or even getting killed. But there are other risks. How credible are journalists’ war-time sources?

In the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the picture of what is happening can vary sharply, depending on what the source is. If it is the Russian propaganda machinery, which also includes pro-Kremlin bloggers “embedded” in Russia’s military in the war zone, then you will get the pro-Russia view; if it is sourced from Ukraine, then it is likely going to be an entirely different view.

In Gaza, journalists covering the conflict face significant challenges. First, there are the restrictions. Israel has not allowed foreign journalists to enter Gaza. As a result, Western correspondents (as well as Indian media outlets that sent their representatives there) have reported extensively on the grief of Israeli families, but they miss a vital aspect of the story by not being able to witness the situation firsthand in Gaza. Without experiencing the prayers Palestinians make when they lose loved ones or learning about the life stories of those who have been killed, the coverage of Gaza remains incomplete compared to the coverage of Israel.

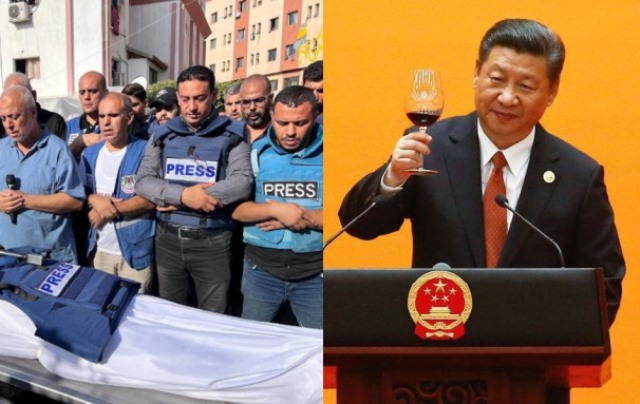

Israel has been steadily suppressing news reporting in the Gaza Strip. Journalists have faced danger, with some killed or wounded, media premises destroyed, and communication disruptions. There is a looming threat of an all-out media blackout in Gaza.

Journalists also face entry bans in Gaza. Since Israel blockaded the area 16 years ago, journalists cannot enter the Palestinian territory without authorisation from Israeli authorities. In addition, there could be further restrictions on Muslim journalists as three Muslim journalists from MSNBC—Mehdi Hasan, Ayman Mohieddine, and Ali Velshi—were suspended. This decision coincided with escalating tensions in the Gaza area.

On the other side too, Hamas, the ruling group in Gaza, has imposed (and later rescinded) some restrictions on journalists covering the conflict. After the recent conflict in Gaza, Hamas issued sweeping new restrictions on journalists in the Palestinian enclave. These rules included not reporting on Gazans killed by misfired Palestinian rockets; and avoiding coverage of the military capabilities of Palestinian terror groups. However, these guidelines were rescinded after discussions with authorities in Gaza. The Foreign Press Association (FPA), which represents international media, expressed that such restrictions would have been a severe limitation on press freedom and safety. Hamas confirmed the reversal and stated that there are currently no restrictions.

For journalists, trying to cover a war objectively and without bias could be an oxymoron. Most journalists are dependent on one or the other side of the warring nations. If reporters and photographers are in Israel covering what is going on in Gaza, you can expect their reports and dispatches to reflect the Israeli view of things; if they are on the other side, then the views could be quite different. Over the past nearly two years, making sense of who is making progress or suffering more losses in Ukraine has become a complex business: you either get the Russian view or the Ukrainian view, none of which might be the “true” picture.

The Cosmic Blueprint of Xi Jinping

There is a photograph that you can find with relative ease on the Internet. It shows China’s supreme leader and President Xi Jinping, flanked by Russian President Vladimir Putin, United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres, and some two dozen top dignitaries from around the world. The photograph is from the third Belt & Road Forum for International Cooperation that was held on October 17 & 18 in Beijing.

It also marked the 10th anniversary of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, a global infrastructure and investment project announced by Xi in 2013. Many see this as part of China’s and Xi’s larger vision of a blueprint for a new world order to challenge the existing international system that it feels is unfairly skewed in favour of the United States and its allies.

Xi’s vision transcends mere governance and is more of a cosmic plan to reshape China’s role, influence, prominence, and, indeed, dominance of the world.

China was once happy to hide its capacities–economic, military, and cultural–and bide its time. It is no longer content to do so. Xi, who is on an unprecedented third term at the helm of his nation, wants to redefine the norms, dismantle existing “western biased” hierarchies and meld together a world where China’s rise is unstoppable. This vision unambiguously pervades every forum, conference, policy formulation, and international strategy that China now espouses.

The Belt & Road Forum was no different. The heads of states who attended it hailed China’s strategy and Xi’s vision. Notably, the United Nations’ Secretary General was a participant at the forefront of the forum.

For the West, Xi’s gambit resembles a tectonic shift. American wars overseas, erratic foreign policy shifts, and deep political polarisation have eroded confidence in US global leadership. Moreover, within the US, opinions, support, and allegiances are sharply polarised and divisive, raising questions there and elsewhere in the world about the relevance and effectiveness of a US-led world order. Is its approach sustainable? Can it navigate the tempests of climate change, geopolitical tensions, and humanitarian crises?

As China’s assertiveness grows, the West faces a choice: adapt or resist. Xi’s alternative model—multilateralism reframed as great-power balancing—tempts some. Yet, lurking beneath are shadows of Beijing’s iron-fisted rule—surveillance, censorship, and repression.

Where does India fit into this? Thus far, India’s approach has been cautious as it tries to balance ancient wisdom and modern ambitions. India seeks economic ties with China while guarding its strategic interests. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) looms large—an infrastructure web that binds nations but also raises sovereignty concerns. India is not a signatory to that initiative.

India’s strategy has been a sort of tightrope walk where it has tried to tango with both the West and with Beijing. It wants to harness economic opportunities from both, yet remains wary of Beijing’s territorial assertiveness and military buildup in the Indo-Pacific.

Xi’s vision does resonate with a large swathe of regions and countries around the world, including predominantly developing nations in Asia, Africa, and South America. His vision exhorts countries to forge creative coalitions—beyond simplistic divisions of democracies versus autocracies. North Korea and Iran share this stage with moderate, modernising nations. The global future, Xi suggests, demands nimble alliances.

In this scenario, India, which has had a rich history of alliances with international partners, has to traverse a shifting landscape. As the most populous nation in the world and with hundreds of millions of young people with high aspirations, India would ideally like to have a louder voice in the emerging new order, and not merely be a spectator. For that to happen, perhaps it is time for India to review its tightrope-walking style of geopolitical strategy and be more decisive.

For more details visit us: https://lokmarg.com/