This summer when India held its gargantuan parliamentary elections, in seven phases and spread over more than 40 days, the cost of holding them were estimated at ₹1.35 lakh crore. For the sake of comparison, India’s real GDP or GDP at constant prices is estimated at Rs 173.82 lakh crore. Another comparison: the spending on the 2020 US presidential election was estimated at Rs 1.2 lakh crore.

In the world’s most populous country with nearly a billion eligible voters, holding elections is a costly affair. Countrywide parliamentary elections like this year’s are hugely expensive but so are state and union territory assembly elections. This year, eight states have either already held elections or will do so in the remaining months.

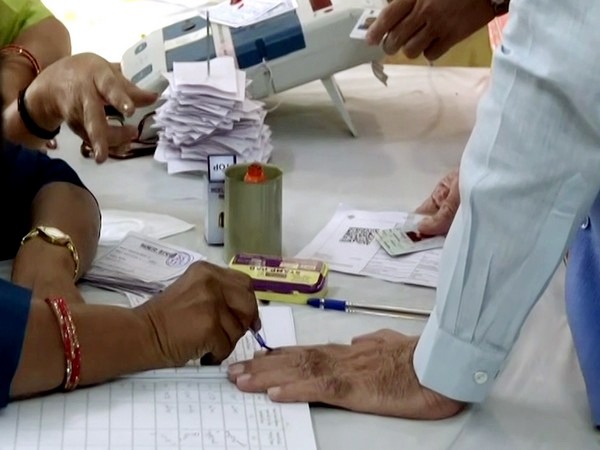

Currently, assembly elections are being held in the union territory of Jammu & Kashmir in three phases. Elections in J&K are being held for the first time since the abrogation of Article 370 on August 5, 2019. The previous assembly elections in the erstwhile state were held in 2014. In a sensitive region such as J&K, the cost of holding elections can be higher because of security concerns.

The spiraling costs of holding multiple elections is one of the reasons why India’s government led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi is serious about its “One Nation One Election” proposal. On September 2, the government issued a notification constituting a high-level committee, headed by the President of India, to examine the issue of simultaneous elections.

Costs are certainly one concern that the government has. The sheer size and scale of an election in India can be staggering. In the 2024 parliamentary elections, approximately 12-15 million polling staff and security personnel were involved; there were more than a million polling stations; hundreds of thousands of civil servants were deployed for election management; and thousands of election observers and micro-observers were needed.

Besides human resources, equipment was required. Around 2 million Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs); a similar number of Voter-Verifiable Paper Audit Trail (VVPAT) machines had to be deployed; and millions of vials of indelible ink were used to mark voters’ fingers after they had cast their ballots.

Then there were costs such as transportation: thousands of vehicles for transporting personnel and equipment; and helicopters and boats for reaching remote areas.

A general election is held on a national level and, understandably, the cost of holding it is enormous. But state elections are also expensive. India’s largest state, Uttar Pradesh, has nearly 200 million people but even a relatively small state such as Mizoram in the north-eastern region has a population of more than a million. With numbers such as that the logistics can be complex and the costs huge.

The proposal of the Modi government is for holding simultaneous elections for both the Lok Sabha (lower house of the Indian Parliament) and all state legislative assemblies.

What would this mean? The proposal suggests synchronising the election cycles so that voting for both national and state legislatures happens at the same time, typically once every five years.

The government argues that conducting simultaneous elections could significantly reduce the overall cost of organising multiple separate elections by eliminating duplication of the resources used. It could also streamline the election process and reduce the burden on administrative and security forces that have to be deployed to ensure that the elections are held fairly, peacefully, and smoothly.

Less frequent elections might allow governments to focus more on governance and policy implementation rather than constantly being in “election mode.” The government and supporters of the concurrent election model think that it could reduce the frequency of the model code of conduct coming into effect and, thereby, slowing down government decision-making and implementation.

Yet, the proposal has stoked criticism, particularly from the Opposition and from regional political parties, which play a significant role in Indian politics in the states.

A model for simultaneous elections could undermine local issues that voters have while voting in state assembly elections. State-level issues might not get the importance they deserve and could get overshadowed by national narratives during elections.

Also, while holding one huge election across the nation, encompassing parliament as well as the states, could reduce duplication of resources and time spent, it could still be a logistical nightmare.

There are 543 Members of Parliament (MPs) that voters elect in the general elections. If all of India’s 28 states and union territories (UTs) are taken together, there are more than 4,000 seats in legislative assemblies across all the states and UTs. Organising simultaneous elections for all these assemblies and parliament can require several phases and a complex plan that can conceivably be a daunting exercise.

The greater concerns relate to issues such as provisions in India’s Constitution, which currently allows state assemblies to be dissolved mid-term (before the five-year term is over) if needed. If elections are to be held simultaneously, this provision of the Constitution would have to be significantly amended.

Less frequent elections may also reduce the opportunities for voters to express their views and opinions on a government’s performance and, hence, as some argue, curb democratic rights.

In India’s federal structure, Indians often vote differently in state elections than they do in the general elections. Opponents of the one election model are apprehensive about a prevailing national mood or sentiment disproportionately affecting the outcomes at both levels and possibly leading to a less diverse representation.

The Opposition’s View

Not surprisingly, India’s Opposition parties have argued that the proposed system could undermine India’s federal structure by aligning state politics too closely with national politics. They fear it may lead to the dominance of national issues over local ones, potentially marginalising state-specific concerns.

There’s also concern that simultaneous elections might benefit larger national parties over regional ones. Smaller parties often rely on state-level issues to gain traction, which could be overshadowed in a combined election.

Some opposition members have expressed concerns that aligning all elections could concentrate too much power, potentially leading to autocratic tendencies.

Yet, the signals are clear that One Nation One Election will become a reality. Last week, when the high-level committee referred to above unanimously recommended the proposal, Prime Minister Modi posted on X: “The Cabinet has accepted the recommendations of the High-Level Committee on Simultaneous Elections. I compliment our former President, Shri Ram Nath Kovind Ji for spearheading this effort and consulting a wide range of stakeholders. This is an important step towards making our democracy even more vibrant and participative.”

As for those not in favour of the proposal, they can probably seek solace in the phonetic abbreviation of the new system: “ONOE”.