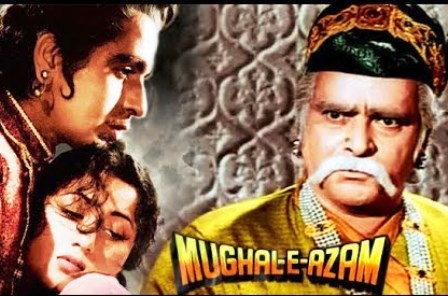

Mughal-e-Azam, released six decades ago on August 5, 1960, remains a landmark for the Indian cinema. It can also be a mark to measure much that happened then and is happening now.

Twelfth years into the independence, despite problems galore, a poverty-stricken India had proved the Winston Churchills wrong by staying united and ticking. The world was taking note of its global affairs (Korea, Non-Aligned Movement, UN peacekeeping and more) and achievements in art and culture (Ravi Shankar, Raj Kapoor, Satyajit Ray and more). Even critics like Nirad Chowdhury and V S Naipaul couldn’t ignore India. Jawaharlal Nehru was leading a secular democracy, howsoever flawed.

Six decades hence, the world’s largest democracy and movie-making nation (majority bad ones) does have a global reach. It is economically stronger with a bigger place in a more complex, competitive, world. But its image as a pluralist, inclusive nation that the world has known and come to expect has taken a beating. It is becoming the anti-thesis of what Mughal-e-Azam was and is all about.

The story of Jalaluddin Mohammed Akbar (1556-1605 AD) the third Mughal Emperor, his Hindu Queen Jodhabai and their only son Salim, later to become Emperor Jehangir, was and is celebrated for depicting mutual respect and tolerance among the Muslim rulers and their Hindu subjects. History calls Akbar ‘Great’ because rather than fight them, he had consciously struck alliances with the Rajput rulers. The film makes no claims to historical accuracy, though. But the anniversary comes when its ethos is being challenged and history itself is sought to be re-written.

ALSO READ: Devdas, The Show Isn’t Over Yet

Rachel Dwyer, author of the book “Filming the Gods: Religion and Indian Cinema”, says Mughal-e-Azam highlights religious tolerance between Hindus and Muslims. Her examples include scenes depicting the presence of Queen Jodhabai, a woman and a Hindu, in Akbar’s court. Anarkali, the courtesan Salim loves and to get whom he rebels against the father, sings a Hindu devotional song.

Celebrating Janmashtami, Akbar is shown pulling a string to rock a swing with Krishna’s idol. Film critic Mukul Kesavan writes that he was unable to recall a single other film about Hindu-Muslim love in which the woman is a Hindu.

One sequence needs citing. Durjan Singh, Salim’s Hindu military aide, is seriously wounded while rescuing Anarkali from prison. On his death, the Hindu priests and doctors let Anarkali pay last respects to her saviour. She spreads on him her dupatta, the ultimate symbol of modesty for a traditional Muslim woman.

The film’s other theme is justice. A vanquished Salim is arraigned before the court and offered a pardon provided he abandons Anarkali. He defies and is sent to gallows. Akbar keeps word given to Anarkali’s mother, the maid who had brought him the news of Salim’s birth. He circumvents his own order to bury Anarkali alive, lets her escape into exile and suffers the odium.

The film was released amidst great fanfare and expectations. A 12 year-old, I remember seeing the milling crowds before a huge cut-out of Akbar and Salim in full battle gear outside the newly-built Maratha Mandir theatre in Mumbai.

Ranked as India’s ‘greatest’ by film historians, the film held the record of being, both, the most expensive and also the biggest grosser at the box office for 15 years. India has not seen anything so grand and opulent, before and since. Indeed, everything about it was excessive, surpassing all film-making norms.

It would arguably hold the record of taking the longest to complete if counted from being conceived by a young Karim Asif in 1944 to being shelved during the Partition turmoil, a complete change of the star cast and even a financier, and taking almost nine years to complete.

Shapoorji Pallonji, a newbie to film financing, agreed to produce and finance solely because of his interest in Akbar. He, too, had doubts when the budget of each department of the film exceeded. He never financed another film.

Dilip Kumar, perhaps the only survivor of the mega project, when he could talk (in his late 90s, he cannot any more), said in a 2010 interview that the long period became of no consequence to those involved as each person was deeply committed.

He played a largely subdued Salim to theatrical Prithviraj Kapoor (Akbar) and Durga Khote (Jodhabai). Dilip had reservations about acting in a period film, but was assured a free hand. “Asif trusted me enough to leave the delineation of Salim completely to me,” Dilip said in his 2010 that interview. By contrast, Madhubala who was keen on the role, pipped Suraiya to it.

The soundtrack was inspired by Indian classical and folk music and composed by Naushad. Of 20 songs, some had to be left out. Included was a rendering by the legendary Bade Ghulam Ali Khan. He reportedly charged ₹25,000 when Mohammed Rafi and Lata Mangeshkar took ₹300 per song.

ALSO READ: Forever Fragrance Of Kaagaz Ke Phool

The theme based on a 1922 play by Imtiaz Ali Taj attracted many, from a ‘silent’ one to a ‘talkie’ by Ardeshir Irani. When Asif’s project was seen as abandoned, one of his writers, also a director, Kamal Amrohi, planned to make a film on the same subject. Asif convinced him to shelve it. The same play prompted Nandlal Jaswantlal’s Anarkali, starring Bina Rai and Pradeep Kumar. With memorable songs, it became the highest grossing Bollywood film of 1953.

Made in black-and-white, Mughal-e-Azam had a seven minute song-and-dance sequence, “pyar kiya toh darna kya”, shot in colour. The set conceived as sheesh mahal (glass palace) was fitted with numerous small mirrors made of Belgian glass. It took two years to build and cost more than ₹1.5 million (valued at about US$314,000 in 1960), more than the cost of an entire film in colour those days.

The mirrors’ excessive glare made filming difficult. Wikipedia records that foreign consultants, including British director David Lean, advised Asif to drop the idea. But Asif spent days to have wax applied to each mirror to reduce the glare.

Lachhu Maharaj was on board for choreography and Gopi Krishna performed. Among the myriad problems was one of a seriously ailing Madhubala not being able to deliver on intricate Kathak moves when it came to girki (spinning one’s body). A male dancer, Laxmi Narayan, performed that portion. He wore a mask matching her face made by Mumbai craftsman B R Khedekar.

Besides Amrohi, three of the best film writers of the day, Amanullah Aman, Wajahat Mirza and Ehsan Rizvi were on board. None knows how they collaborated. Their “mastery over Urdu’s poetic idiom and expression is present in every line, giving the film, with its rich plots and intricate characters, the overtones of a Shakespearean drama,” Times of India wrote on the film’s 50th anniversary.

The battle scenes used 2,000 camels, 400 horses, and 8,000 troops, mainly from the Indian Army’s Jaipur Cavalry, 56th Regiment. Bollywood could not better those scenes for several years despite technological advances.

Many fell sick filming it in Rajasthan’s desert. Armour and weapons were borrowed from the Jaipur royalty. But even the burly Prithviraj found them too heavy. Aluminum replicas were got made.

Each sequence was filmed three times as the film was being produced in Hindi/Urdu with plans for Tamil, and English versions. Dubbed in Tamil and released in 1961 entitled Akbar, it flopped commercially. Asif abandoned the English version for which he had engaged Romesh Thapar and British actors.

Years later in 2004, Mughal-e-Azam became the first black-and-white Hindi film to be digitally coloured, and the first in any language to be given a theatrical re-release. The colour version was also a commercial success.

Speculation abounds on its cost. It has ranged from cost ₹10.5 million (about US$2.25 million at the time) to ₹15 million (about $3 million). That made Mughal-e-Azam the most expensive Indian film of the period.

There is more to and about the film than the space here can accommodate. As a piece of cinema-art, it is impossible to recreate those conditions. Investors, national and global, are too conservative and calculating to afford and risk such a venture.

There is no Asif, the talented and passionate, but highly erratic man, to rally the best writers, composers, cinematographers and actors. Are audiences ready?

Mughal-e-Azam came in an era when Hollywood too was making films that were grand spectacles. It doesn’t any more. The way Asif made it, warts and all, could itself be the subject for a mega film. But then, India long ago stopped making a film like Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959) that, by sheer coincidence, was on the life of a film-maker.

The writer can be reached at mahendraved07@gmail.com