Analysing India’s defence budget for a Mumbai-based newspaper in 1983, this writer projected a significant budget hike and plans for many ships and equipment for the Navy. It caused ripples in defence circles, which worried the Navy. The late Admiral R H Tahiliani, then heading the Western Naval Command, entreated my editor, late R K Karanjia: “We are a silent service. Please help us stay that way.”

The Navy may still prefer to remain ‘silent’ to avoid rivalry with other Services, but has got the best deal this year. The 2025-26 defence budget has risen by 9.5 per cent to ₹6.8 trillion ($75 billion), making it the world’s fourth-largest after the US, China, and Russia. The ‘silent’ part is ₹57,950 crore, which is 41 per cent of the total ₹140,691.24 crore modernisation budget in 2025–26 BE. And lo! It has beaten the Army, allocated ₹27,421 crore (19.5 per cent), and the Air Force, allocated ₹54,570 crore (39 per cent).

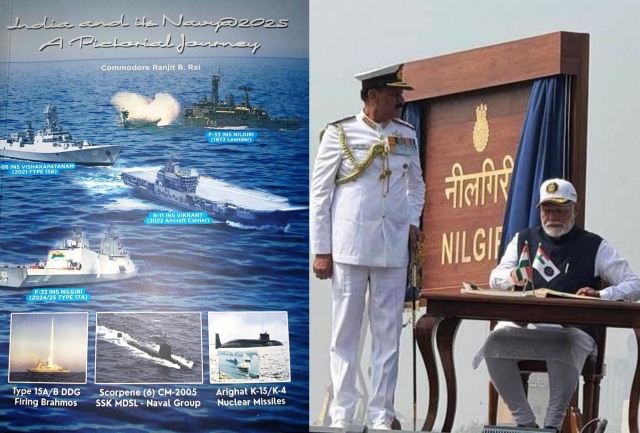

An enthused defence analyst, Commodore Ranjit B Rai (retd.), writing in his latest book, India and Its Navy@2025, which is also “a pictorial journey”, “looks into the crystal ball”, and predicts that “the Indian Navy@2025 and beyond will go into the nation’s best years in service.”

This year began with Prime Minister Narendra Modi on January 15 commissioning the sixth Scorpene class submarine ‘Vagseer’, the first of seven 6,400-ton Type 17A, ‘Nilgiri’ and the last of four 6,700 ton Type 15B ‘Surat’ with AI-assisted systems at the Naval Dockyard in Mumbai. All three warships were built by the public sector Mazagon Docks Limited (MDL) which deserves credit for the scope and speed of construction to deliver the three platforms in time. Nine ships are scheduled to be commissioned in 2025. Rai welcomes the Navy’s order book for the year as ‘aspirational’ and ‘timely’.

Most of the Navy’s sea platforms are now made in India. From a Buyer’s Navy, today it is a builder’s Navy and a collaborator of weapons and systems. Navy’s Design Directorate has increasingly designed its warships including an aircraft carrier INS Vikrant and has entered the export market. Last century’s slogan of “self-reliance,” now translates to ‘atmanirbharta’.

However, it is impossible to go it alone in a complex, competitive world that poses increasing security risks. The IN ships have the Indigenous 750 km range ‘Brahmos’ ship and land attack and the 60 km ‘Barak’ anti-aircraft missiles, supported by the latest guidance radars, like the Multi-Function (M/F) Star from Israel and the Lanza air radar supplied by TATA Advanced Systems within the framework of a technology transfer with the Spanish firm Indira.

The Navy’s two medium-sized aircraft carriers INS Vikramaditya and INS Vikrant fly the MIG-29K fighter planes and operate the latest Sea Hawk MH60R and the older Kamov 28 helicopters. Orders for 26 Rafale M have been placed. They can be force multipliers in the region with decisive Indian Air Force fighters with re-fuelling capability and sea-going surveillance and transport and fighter assets in a sea-air strategy.

The naval inventory has 132 ships and 18 submarines, including two SSBNs, INS Arihant and Arighat, with long-range underwater launched nuclear missiles for deterrence, including 240 aerial assets. In 2024, the Navy’s 68,000-strong men and women clocked 6.500 ship and 700 submarine days and 50,000 flying hours. It seized $4.5 billion worth of contraband, rescued over 1,000 persons, and confronted the Houthis of Yemen in action in the Red Sea, besides continuing operations against piracy in the Horn of Africa.

This is a small part of the enormous task of defending a 7,500 km coastline, marking maritime presence, and showing the Flag in a vast region stretching from the Gulf of Hormuz to the Malacca Straits and taking part in national and foreign exercises. Located amid the Indian Ocean Region, as a part of the strategic Indo-Pacific, Rai notes, India has had to catch up historically after centuries of looking north in a continental mindset to defend the land frontiers.

ALSO READ: Know Your Sea, Cadet

A former Director of Intelligence and Director of Operations, he highlights the many growing security challenges as the IOR becomes the arena of the US-China rivalry. In the immediate neighbourhood, besides China wooing the South Asian nations with its deep pockets, Belt and Road Initiatives and ready weaponry, the abrupt changes in Bangladesh last year and the return of the Pakistani factor make India’s eastern flank and the Bay of Bengal vulnerable yet again.

The IN attacked and destroyed the Karachi harbour’s oil tanks at Kemari and Pakistani naval assets during the 1971 war. Repeating it would be challenging today, with the Chinese presence and assets and interests in the region, at Gwadar, and in the IOR. Still, Rai says, the Navy’s exercises for various contingencies and war plans are always made to situate various scenarios.

India has always resented Chinese warships surveying and snooping in India’s EEZ and calling at Sri Lanka ports. Although playing the China card, Sri Lanka was a friendly neighbour until India got involved in its domestic conflict in the 1980s. Successive governments thereafter have oscillated between policies that are either soft to India or pro-China. The present president, Anura Kumara Dissanayake, although an erstwhile Marxist activist, has assured India that Lanka would not allow its territory to be used against India.

Rai is upbeat. He says India today is a de facto nuclear power with nuclear bombs and missiles and has two nuclear-powered submarines (SSBNs). “India’s animal instincts have been released and begun to show after years of nomadism when “IOR and Indo-Pacific are regions of contestation with China’s phenomenal rise to challenge the US interests.” He stresses that the present government’s fillip to the defence sector must be sustained.

No Navy can operate alone in a conflict zone. Among many things, Rai emphasises that the IN retains its ‘forte’, the knowledge of the English language, to converse with navies worldwide. Besides, most IN commands, documentation, multi-national exercises and interoperability procedures are in English. As the only military service that operates beyond the borders, it wants to retain this advantage over others. This is essential with warfare going digital and artificial intelligence driving science and technology. Advocating close Navy-Air Force synergy as part of an Air-Sea Maritime Doctrine, he says it is needed to harness India’s maritime sea power in the IOR, which may be extended to West Asia and Southeast Asia in the future.

The IN’s leadership hosts a world-class collaborative maritime information fusion centre for the Indian Ocean Region (IFC-IOR) near Delhi with 12 International Liaison officers and a clear mission to enhance Maritime Domain Awareness (DMA) and coordinate activities through information sharing, cooperation, and proficiency development. Its beginnings and growth have been synonymous with the IN’s and partner nations’ growth in recent years and have been widely used in humanitarian situations and COVID-19 to manage the movement of ships.

Overall, Rai pushes for a national maritime strategy that will address the entire range of issues in the waters around India. This strategy is needed because China lacks sea space and is looking to influence the IOR, while India has sea space. “With technology, the Chinese have converted rocks into islands and fortified them with missiles and airfields, disregarding the legitimate claims of the Philippines, Vietnam, Brunei and Singapore by blatantly quoting historical charts for claims to the South China Seas and shredding United Nations Laws of the Seas UNCLOS (1982) to the winds.” India is considered a swing state in the US-China rivalry in the Asia-Pacific Region and must make the best of its location and maritime strength.