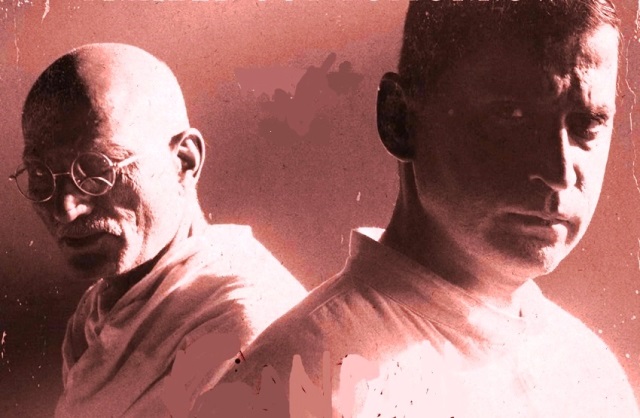

As India celebrates 75 years of its independence from colonial rule, a debate rekindles a clash between the ideals Mahatma Gandhi espoused and those that caused his assassination. The timing seems perfect for the Gandhi-Godse: Ek Yuddh film. It is being released on January 26, just four days short of the day he was killed 75 years ago.

It is based on a double assumption: that Gandhi survives the attempt on his life and engages in a debate with his unsuccessful assassin, Nathuram Godse. The clash of ideas forms the crux of the film, leaving the verdict to the viewers, and the people outside, not just in India but wherever Gandhi is known, understood and appreciated.

The basic idea is not new. It formed the hypothesis of Godse @ Gandhi.com, a play scholar-writer Asghar Wajahat wrote in 2010. It has been performed in different languages in different cities and generated a measure of closed-door debate. The film now seeks to take it to larger audiences.

Still recouping from the bullet wounds, Gandhi meets Godse in jail, outside of the prison cell and without being held in chains. He refuses to depose before Godse which helps to reduce the latter’s jail sentence.

More importantly, both engage in a debate. A clash of ideals, not a jugalbandhi, it shows Gandhi calm and all smiles, while Godse is angry, tense and frustrated, unwilling and unable to agree with everything Gandhi says. One preaches ‘ahimsa’ the other rejects it. One wants to carry all citizens along, but the other pitches only for the Hindus. Godse continues to hold Gandhi responsible for the country’s Partition and vows to undo it. No appeasement of Muslims, be they in Pakistan or those who have stayed on in India.

It is an open-ended debate. The two engage in what resembles the current Hindutva debate, with the deification of Godse, questions on the relevance of non-violence, re-writing of history and the “me too” factor in who won the country’s freedom, and how.

The Gandhi-Godse debate is unique, and also essential in the present times when Gandhi sought to be appropriated first, to be questioned, dismissed and possibly discarded. His most likely replacement would then be the culture that nurtured Godse, and the reliance on violence that Gandhi preached against.

The filmmakers may aim to be neutral and objective. But this writer must inject a disclaimer, for whatever it is worth, and take the Gandhian side.

The debate takes place amidst decades of indifference and lip service paid to Gandhi’s ideals. So, it is a critique of not just his baiters, but also of those who claim to follow him but lost their way post-Independence.

In the film, Gandhi quits the Congress when his followers — Nehru, Patel and Azad – reject his call to disband the party now that it has helped achieve the country’s Independence. (This is an issue that Congress baiters have found handy). He also launches community development projects as per his ideas and leads anti-government protests. They are thwarted by his followers now ruling the country. He is imprisoned in independent India even as people continue to revere him as “the Father of the Nation.”

Gandhi is put in the cell where Godse is serving his prison term. As the two meet, this allows for the resumption of the debate over Akhand Bharat, the Partition of India, on Pakistan and Hindutva. Both re-evaluate their ideas. Gradually, Godse and Gandhi understand each other, even as they disagree.

Gandhi maintains that Godse is not the wrong man. Only his views are wrong. Although Godse is influenced by Gandhi’s thoughts and personality, to what extent, remains unstated. Critics are likely to ask: Is he the new anti-hero?

ALSO READ: Gandhi or Godse – Kindly Choose One

Gandhi’s own frailties come to the fore in a story within the story. Sushma, his young woman devotee, loves Naveen, a college teacher. Gandhi separates the two. He wants Naveen to continue “serving the nation” as a teacher, without distracting Sushma’s mission. He resents Naveen secretly meeting Sushma and asks Sushma to quit his ashram.

Gandhi’s controversial views on celibacy come into play. With this new weapon in his arsenal, Godse attacks Gandhi for being unfair, especially to his women devotees, by insisting that like him, they practice celibacy. Gandhi is made to realize this by his deceased wife Kasturba. She comes into his dream and pleads for the young couple on an issue that she had suffered when alive. Gandhi relents and blesses Naveen and Sushma’s marriage in jail. Is it Kasturba’s persuasion that works or Godse’s trenchant criticism?

How much of all this will be accepted/rejected by Gandhi’s acolytes and how far do today’s Hindutva followers feel vindicated? The film’s interpretation of Godse and his “filmy re-trial” shall remain to be judged by those who will watch the film.

Given the current times, the film could well boost Gandhi-baiting, also Godse’s advocacy. The Congress has already launched an agitation, while the BJP camp defends the film as a work of fiction.

Producer-director Rajkumar Santoshi has told the media that Godse’s viewpoint has not received adequate space in his view. Besides Wajahat’s story, he has incorporated portions of Godse’s statement recorded in the court during his 1948 trial. Godse was eventually convicted and hanged. “My take is, I might dislike the person but I will fight for that person. It has been done in a democratic setup”, Santoshi says. “I request people to watch the film with an open mind and not come to theatres with any preconceived notions. Those coming with an open mind will truly enjoy the film,” he appeals.

Santoshi is leaving the film’s conclusions open to public interpretation. So is Asghar Wajahat, the playwright and the film’s writer. The duo want Gandhi versus Godse debated in a true fashion that Gandhi would have approved, whether or not their current lot of his followers and baiters relish.

Save Santoshi himself and music by A R Rahman, the rest of the ensemble has no marquee, only performers. Deepak Antani and Chinmay Mandlekar, both seasoned performers, play Gandhi and Godse respectively.

Santoshi has made films that entertain, some of them with his preferred actor Sunny Deol. The latter is famous for the “dhai kilo ka hath” fisticuffs, and also for using the gun to secure justice on his own terms in the face of vested interests all around.

Santoshi’s heroes have also protected women, taken on the law, screaming the famous “Tarikh pe Tarikh” on the propensity of the powerful to seek postponement of court hearings if they find the going tough. The phrase, incidentally, was used approvingly by a judge in the courtroom recently.

The Gandhi-versus-Godse is a different cinema terrain for Santoshi, but that cannot be a reason for anyone to prejudge his new work. Good filmmakers are known to switch gears and move from popular entertainment to what they consider “purposeful” filmmaking.

As per Wajahat’s play, Gandhi and Godse agree to disagree on their points of conflict in a true gentlemanly fashion. Their respective jail sentences end, dramatically, on the same day, July 5, 1960.

Bidding farewell, Gandhi says: “I shall continue to do what I have been doing and I am sure you will do the same.” Both part with a Namaste. Their respective courses are open, to be viewed and interpreted. Perhaps, the way it is being done now and shall be done in future as well. There is no last word.

The writer can be reached at mahendraved07@gmail.com

Read more: https://lokmarg.com/