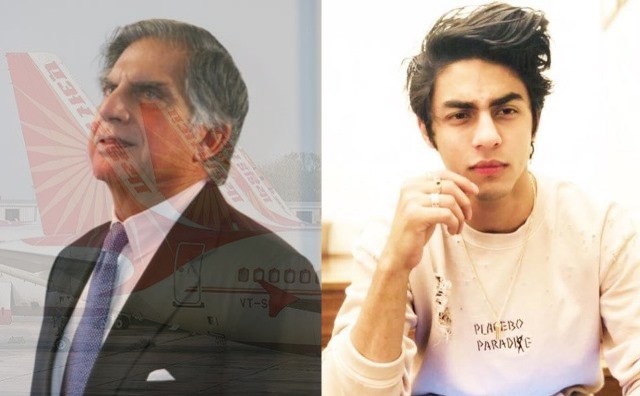

The Tata acquisition of Air India has unleashed high-decibel social media buzz, much of it bullish yelps in favour of the Tatas who were the original owners of the airline before it got nationalised in 1953. The privatisation of Air India has taken 20 years since it was first attempted back in 2000. And the saga of what happened to those attempts and why they were unsuccessful over the past two decades is well-documented. In that context, the Tata acquisition is certainly welcome but could it be too early to rejoice? With the acquisition of the flagship airlines, the Tata’s have also inherited a daunting challenge.

In the best of times, the air travel business can be a dicey proposition. In the wake of the Corona pandemic, things have been devastating for the sector. A recent McKinsey & Co. report on the prospects for the sector post Covid estimates that in 2020, global industry revenue totaled $328 billion, around 40 percent of what it was in 2019. For perspective, it means the sector’s revenue in 2020 is the same as what it was in 2000, that is, two decades ago. What is more, McKinsey estimates that the sector will continue to remain smaller (and may even shrink further) in the years to come. To be sure, the consulting firm projects that air traffic won’t return to 2019 levels before 2024.

Air India has an accumulated loss of Rs 77,953 crore and debt of Rs 61,562 crore. And although the pandemic may have wreaked havoc on the company as it has on every airline in the world, it must be noted that Air India never made profits since 2007 when the state-owned domestic airline, Indian Airlines, was merged with it. That is, no profits at all in the past 14 years.

So, to bring things back to the ground, the Tatas have a task on their hand. The global environment for the aviation business is something that airlines companies have little control over besides being smartly reactive to it. But Air India has a host of other issues that have to be tackled. First, it may be the Tatas’ largest interest in the sector but it is by no means their only aviation business: besides Air India, the Tatas have Air Asia in which they own a nearly 85% equity stake; and Vistara in which they own 51% stake (Singapore Airlines has the rest). It would be interesting to see how the Tatas configure their airlines business in a way that is best for each of these entities. Will they go for a merger? Or operate them independently?

Second, there is the question of management of Air India.The airline has not had a professional CEOin a while and it is a bureaucrat, the civil aviation secretary of the Government of India who has been officiating in that role. The Tatas would have to embark on a search for a suitable person to helm the company.

Third, there are the financial liabilities and operational losses. The Air India acquisition also comes with retirement benefits that the airline pays to nearly 55,000 retired employees. But that is small change compared to the investment needed in modernising the airline’s fleet of aircraft. Air India and its subsidiary has 117 aircraft, while its subsidiary the low-cost Air India Express has 24. Many of these need to be replaced or equipped with new engines and that would entail hefty expenses.

Finally, the airline operates on many routes that are not remunerative. During its years under government ownership, meddling by the ministry has often led to adding routes on political and not economic considerations. Air India’s new owners will need to sort those out as well. For the Tatas, getting back control of what they once owned (very long ago) is only the beginning of a long journey.

No Bail For Aryan Khan

A raid conducted by the Narcotics Control Bureau on October 2, reverberated through newsrooms and social media platforms throughout this week. While eight people were arrested from a party on a luxury cruise ship, Cordelia, on Mumbai’s shores, the one name among them that has hogged all the limelight is Aryan Khan, son of Bollywood superstar Shahrukh, “King Khan” or SRK as he is better known.

Fans are frantic in their protests that he is being targeted by the Narendra Modi government for his closeness to the Thackeray family. They cite the role of a local BJP supporter who gave the tip off and accompanied the NCB sleuths during the raid, to drive home the point that the Centre wants Khan to “fall in line” or else. On the other side of the debate are those who consider Bollywood a drug den, where,they allege, drug abuse is rampant and there is a huge demand for illegal drugs. This group cites the drug links that surfaced after the death of talented young actor Sushant Singh Rajput last year, involving top film stars.

The debate spilled over to political circles this week. NCP and Shiv Sena leaders, including chief minister Uddhav Thackeray have questioned the legal alacrity in drug bust case, conrasting it with the lethargic action in Lakhimpur case where a union minister’s son was involved in running over a vehicle on farmers.

Both sides have ignored the facts. First, the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act has strict provisions to keep those charged under it behind bars. This means the bail under NDPS is difficult to get. In comparison, the bail provision under road accidents comes under culpable homicide. So comparing the Lakhimpur with Mumbai drug bust is unfair (Salman Khan allegedly ran his SUV over Mumbai footpath dwellers in 2002 and was granted easy bail, and later acquitted).

However, coming to the drugs case, the NDPS provisions were supposedly made tough to discipline drug dealers and peddlers, not the user. From university students, young corporates, party circuit regulars to hill trekkers and religious Hindu hermits, use of banned drugs is common. From Kumbh festival to Kanwad Yatra, use of psychotropic substances is more a spectacle than a hush-hush matter. Yet, the NCB team targeted only the users, in this case high-profile, clearly raising doubts. In any case, the Modi government at the Centre is now considered, not without reasons, using central investigating agencies to make their critics or opponents fall in line.

What probably in this vendetta politics, the powers that be do not realise that they are playing with the lives of several youth. The prison atmosphere can be an overwhelming experience for an undertrial. In high-profile cases, this may scar their psyche for life. What good can come out by keeping a band of 20-somethings in judicial custody for experimenting with banned substances for an occasional kick? Lawmakers and law enforcers must keep that in mind