A senior Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) official who is also a member of the Lok Sabha from West Bengal remains allergic to all the accolades, including the Nobel in economics, that have come in the way of Professor Amartya Sen for his path breaking work on economics and philosophy and his championing the cause of society’s weaker sections. But this worthy Dilip Ghosh who like many other politicians in the country will not lay any claim to academics but shows his rawness whenever he talks is always looking for an opportunity to run down the global icon in the crudest fashion possible. All his charges against Sen including Sen’s running away from the country, his “theories never helped the country or West Bengal,” a “land grabber” at Santiniketan and his “multiple marriages” go well beyond human decency.

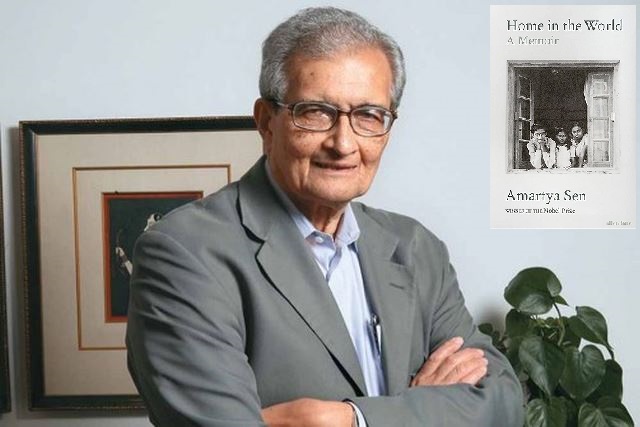

The worlds of Sen and Ghosh will never meet and the latter must not ever have read anything on economics or philosophy or the more recently published memoir Home in the World by Sen. Then why should Ghosh be behaving this unseemly way? Or for that matter why is the vice chancellor of Visva-Bharati, a central university remains unrelenting in first raking up the baseless issue of Sen remaining in unauthorised occupation of 0.13 acres over the 1.25 acres that the university originally gave on lease to his late father Professor Ashutosh Sen and then harassing him in every possible way, including an eviction notice and moves to recover “unauthorisedly occupied land?”

The answer to why all this harassment is happening instead of finding an amicable solution to the land issue, if there really is one, is not difficult to find. Sen has been critical of the policies pursued by the BJP government since it came to power in 2014. Many others too have been critical of the BJP administration to the extent of saying that there has been abridgement of democracy in many ways.

But anything coming from Sen is widely read and discussed both within and outside the country. Much to the concern of New Delhi, the major world newspapers from New York Times to Financial Times to Le Monde will seek interviews with Sen to know what he thinks of the goings on in India. And that is the reason why the powers that be in New Delhi are so sensitive about views expressed by Sen, who is Thomas W. Lamont University Professor and Professor of Economics and Philosophy at Harvard.

Earlier this year, in an interview with Karan Thapar for The Wire, Sen opened up on major national concerns like never before. Here is an encapsulation of what he said. He described the Modi government as one of the “most appalling in the world.” The government’s treatment of the Muslims and the fact that it has no Muslim representation in either house of Parliament are “unacceptably barbaric” to the Professor. The way Muslims are treated is not only unjust and wrong… but it makes India’s culture limited.” India has always been a multi-ethnic country, but the Modi government’s “communitarian and majoritarian policies amount to reduction of India.”

The multiple pluralistic nature of the country is seriously compromised if only the Hindus are counted as Indians. All such things that Sen says leave the government in fits of anger and fury, which is using people like the vice chancellor and Ghosh and also the outfits of BJP such as its IT cell to behave with him nastily. BJP alone might have won 303 seats in 2019 parliamentary election and 353 seats with its allies in NDA. But since the party’s vote share was 37.36%, Sen would categorically maintain that it doesn’t have the support of majority of Indians.

ALSO READ: Amartya Sen – A Life Without Walls

Modi demonetised high-value notes in November 2016 thinking that this would mark the end of unofficial transactions and therefore, generation of black money. To Sen, however, “demonetisation was a despotic action that has struck at the root of the economy based on trust. It undermines notes, it undermines bank accounts, it undermines the entire economy of trust. That is the sense in which it is despotic.” His rebuttal of many other policies of the Modi government, specially the moves that hurt the minorities is long. No wonder there is no love lost between Sen and Modi.

Democracy demands tolerance of what critics may have to say. Going further such opinions if read with consideration they deserve gives a chance to the government for course correction. Unfortunately what we are seeing instead is ministers and BJP party officials harassing the likes of Sen in every possible way. Seeing the agonising times Sen is having over a piece of land Prabhat Patnaik, Professor Emeritus of Jawaharlal Nehru University, is constrained to recall the response of President Charles de Gaulle when he was asked why no action was taken against the famous existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre for his seemingly act of treason asking soldiers of the French Foreign Legion fighting against Algerian war of Independence to abandon the campaign. de Gaulle in his characteristic haut en couleur fashion said “one does not arrest Voltaire.”

It is not that Voltaire or Sartre will get off scot free for commitment of any crime. But at the same time democracy demands that such people should have the freedom to air views even if these cause great amount of discomfort to the powers that be.

Compared to that benevolent approach of de Gaulle to critics of the kind of Sartre, what is seen in India is painful. Patnaik is giving expression to the hurt sentiment of liberal Indians as he writes: “Amartya Sen is an iconic intellectual of this country, and he deserves the nation’s respect not only for his outstanding intellectual work but also for his steadfast commitment to the values upon which modern India is founded, values that have never been officially repudiated by any regime, no matter how much the right-wing may dislike them. And yet, he is being hounded in the most unseemly manner by Visva-Bharati, an institution in whose establishment and growth his family had played a significant role.” One doesn’t have to go beyond reading the chapter ‘The Company of Grandparents’ in Sen memoir to know how determined was Rabindranath Tagore to get Amartya’s grandfather Kshiti Mohan Sen with outstanding classical scholarship, liberal ideas and deep involvement in the wellbeing of society’s poorest people to join him at Santiniketan to “to help Tagore with his work on village reform and rural reconstruction, in addition to contributing to education.”

But salaries at Tagore’s Santiniketan then “were very low” and Kshiti Mohan had a large family to support and therefore, he was reluctant to join the poet for a long time. In great need of an “ally,” which he discovered in Kshiti Moha, Tagore, however, was never “ready to abandon hope.” Sen writes: “Ultimately, Tagore did persuade Kshiti Mohan to come to Santiniketan, where he spent more than fifty contended and productive years – being both influenced by Tagore’s vision and influencing the poet’s own ideas. They also became close friends.” Sen on his part, at the insistence of his mother Amita in particular, spent “ten engaging years at Tagore’s school in Santiniketan.”

Unarguably, Sen remains the most distinguished alumnus of the school and returns to the place where the family has a house called Pratichi (in the possession of the family since 1943) more than once a year from wherever he may be. In a recent tweet the Nobel Prize Committee says: “Amartya Sen’s bicycle played a key role in his research on the differences in baby boys and girls. After his assistant got bit by the children when weighing them, Sen decided to bicycle through the countryside of West Bengal, weighing the children himself.” What is not to be forgotten is the dignity that Sen lends to Santiniketan. Unfortunately, Visva-Bharati of which the Chancellor is the prime minister has its own agenda.

Read More: lokmarg.com