Sanket ‘Katha’ Ray, a documentary film-maker and educator, says OTT platforms are slowly replacing the television programming format

With the democratisation of the medium, young filmmakers have broken the shackles of traditional filmmaking and are exploring stories beyond the studio-controlled environment. They are challenging the Bollywood formula and are bringing in stories which highlight the human condition in modern societies.

Take for example, Nasir (2020), a Tamil-language film directed by Arun Kartick. It is a portrait of a gentle person who negotiates with the communal tension of his surroundings with his poetry. His dreams, the hope for a better future, and his love for his wife, reflect the aspiration of every common man struggling with the complexity of the present-day society.

Another interesting film which captures the human condition is Asha Jaoar Majhe (2014) meaning Labour of Love, directed by Vikram Aditya Sengupta. The film is set against the backdrop of a spiraling recession that hit India a few years back. Faced with the uncertainty of losing their jobs, the film’s two central characters are under constant pressure to sustain their livelihood. However, even in the face of adversity, they seem to possess a serene power. Their demeanor displays a strange, comforting calmness.

One must also reflect on the contribution made by young filmmakers who have chosen documentary films to make their voices stand out. Among them is Payal Kapadia, whose film A Night of Knowing Nothing (2021), is expressed in the form of video-letters during an on-going student protest in a premiere film school.

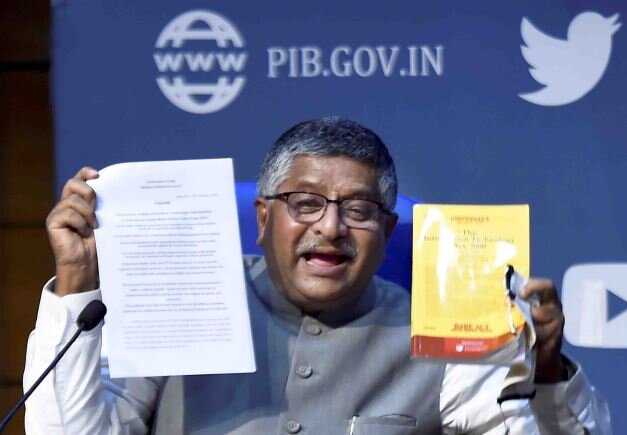

ALSO READ: Apex Court Favours Regulation of OTT Content

These are a few examples, among many, which are shaping a new film movement in India. They are not necessarily entertaining as defined by commercial cinema, but they do portray and chronicle the human condition in today’s time.

OTT platforms are slowly replacing the television programming format. With easy access to the internet, youngsters are getting exposed to newer content every day. OTTs have provided a platform to young filmmakers to exhibit their works, bypassing the tedious and expensive module of theater-screening and television-broadcast. Their work is able to reach the audiences with ease, and a discourse of their work is shared in social media with an immediate effect. Hence, OTTs are proving to be a success among new filmmakers.

However, it is a long way to go as our audiences are still hung over with the typical masala movies. These new wave films are also challenging the film industry, which seems to be shifting its focus from ‘masala’ to meaningful films and web-series, to cater to the ever-growing audiences.

Post-Covid, the film industry, especially Bollywood, adopted the formula of ‘religion’, ‘nationalism’ and ‘us vs them’ to boost the sale of tickets. Apart from Pathan and Jawaan, none of the films really worked well at the box-office. With the onset of OTT and other platforms, the audience has been presented with choices of their liking. They have arrived at an understanding of films which are worth their time and money.

The medium of DVD has been systematically abolished and the films are easily available on the OTT platforms within a month of their release. This phenomenon has led to the decline of theater-viewing. Bollywood stars like Shahrukh and Salman Khan still draw the crowd. Rest of the ‘stars’ are trying to survive via OTTs.

As cliched as it may sound, whether it is a documentary, or a fictional drama, I prefer watching films which inspire me to become a better human being. As a practicing cinematographer and filmmaker, I would like to reach out to the people through various platforms. This includes film clubs and film societies too, which have a tradition of stimulating and insightful post-screening discussions. Not everyone can afford to book cinema halls for exhibiting their films. Hence, Youtube, Vimeo and other OTT platforms play a pivotal role in reaching out to the masses.

(The narrator graduated from the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), Pune, specialising in Cinematography and teaches filmmaking at Dr BR Ambedkar School of Specialised Excellence (SoSE), Delhi. His film This Is My Home (cinematographer and editor) has been showcased at the 17th Mumbai International Film Festival 2022, South Asian Short Film Festival (Kolkata, 2022), 14th International Documentary and Short Film Festival of Kerala (2022), and was nominated for Sony’s World of Film Contest (2021). His other notable works include Village of Warriors (2021) and MidnightMirage (2021).)

As told to Amit Sengupta

For more details visit https://lokmarg.com/