Experiments in

democracy interrupted by long periods of military-led rule have shaped Pakistan’s

life. The difference in this winter of discontent is that for the first time, the

military is being challenged. Ousted premier Nawaz Sharif, addressing protest

rallies through video links from his London home, has named serving Army Chief,

General Javed Bajwa and other top brass.

Voices of some opposition

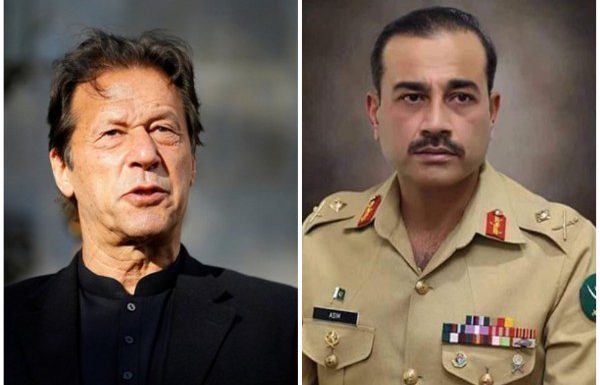

leaders are relatively muted. But when they call incumbent Prime Minister Imran

Khan a ‘puppet’, there is no hiding who the ‘puppeteer’ is. It is tough going

for an institution used to playing the umpire among its proxies, selecting and discarding

them by turns. Questioning it are yesterday’s political adversaries with deep

ideological differences turned allies today. Worse, they include yesterday’s

proxies – called laadla (favourite).

With five ‘jalsas’ (protest rallies) through

October-November and three more lined up for December, the 11-party Pakistan

Democratic Movement (PDM) is gathering momentum. Its Lahore rally slated for December 13 is Nawaz’s

direct challenge to Imran. The battle in the most populous and powerful Punjab could

bring both Khan and the army under greater pressure.

The cacophony is

caustic. When protestors chant “Go, Niazi, Go” their target is as much Imran

who rarely uses this surname, but also refers

to late A A K Niazi, who led the Pakistani forces in erstwhile East Pakistan to

surrender to the Indian Army in 1971. Unsurprisingly,

Khan and his ministers accuse their opponents of taking cue from India.

Analysts say the Army has lost

some of its image as the nation’s ‘saviour’.

But it has had a record of bouncing back and regaining control. It had

done so after losing the erstwhile east-wing and again, after a mass movement

brought Pervez Musharraf down.

Maulana

Fazlur Rahman is the PDM’s surprise Convenor. Like most Islamists, he has remained

on the right side of the military. Then,

the two mainstream parties, PPP and PML(Nawaz), are forever competing.

At the

other end of the PDM’s spectrum are ‘nationalist’ leaders and parties of Khyber

Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan, targeted as ‘secessionists’ by the military,

irrespective of who holds the office in Islamabad.

These diverse forces have combined thanks to Imran’s handling

of the economy that is in dire stress, his failure to hold the prices of

essential commodities and the rising Coronavirus pandemic. Above all, he has been targeting just the

entire opposition with a messianic zeal in the name of corruption. This has

made various agencies and judiciary partisan and parliament redundant.

Support from sections of the judiciary and an

under-pressure-media has helped him. But like most people in power, Khan has

forgotten that all this support is but transitional and the army’s support,

transactional – till he delivers or shows the potential to deliver. He has

shown neither so far.

The Peshawar and

Multan rallies took place despite the government’s warnings of terrorist attack.

Imran also sought to put the fear of Covid-19, like the fear of God, but crowds

broke police barricades and milled at the venue. The Islamabad High Court this

week refused to ban protest rallies saying it had set the standard operational

procedures (SOPs) and now it was for the executive to decide.

A glance at

the military’s role in the country’s life that begun with General (later field

marshal) Ayub Khan, shows that rule by the generals — Yahya Khan, Ziaul Haq

and Pervez Musharraf –has meant that with bureaucracy in toe, the politician

was demonized — with some justification

— in the eyes of the public. They played favourites among the politicians, but

at each end, were forced to return the country to elections and civilian rule.

All these

generals headed the army and ruled directly or through pliable prime ministers.

That script is old, but situation is new. Not formally in charge, the army has

an alleged ‘proxy’ in Imran. During the rule by earlier ‘proxies’ of which

Nawaz was certainly one, the military was not exposed to attacks like the ones

at the four rallies. It is unrelenting

so far and the military has found no answer.

Nawaz

accuses the generals of ousting him and engineering the 2018 election through

which they ‘selected’ Khan. With his entire family targeted for graft and

himself declared an ‘absconder’, he has little to lose. Islamabad is lobbying

hard with London to secure Nawaz’s deportation. But the ‘sheriff’ is unlikely

to relent.

Nawaz’s apparent

aim is to cut off the top few generals from the

lower tiers of the army establishment and thus drive a wedge between the

military’s leadership and rank and file.

There is

dissatisfaction among the top brass at Bajwa’s extension as the Chief that Khan

worked out, upsetting the seniority line up. A media expose of graft involving

retired general Asim Bajwa is

attributed to an insider’s leak. He had to resign recently as Khan’s key Advisor,

a ministerial post.

The PDM has

declared a change of government by January next. This is political rhetoric.

But then, Pakistan has witnessed many changes triggered by mass movements.

Post-Multan

rally, coming weeks should see more detentions of the opposition leaders and

curbs on media. Alarm

bells are ringing over this showdown that neither could decisively win. The

Imran government is definitely stirred and on the back-foot, but is not shaken,

yet. Professional groups like lawyers and media who had helped bring down

Musharraf are keeping distance. The man on the street, used to shenanigans by

politicians of all hues, is aware that at some stage, the military could

intervene to ‘discipline’ everyone.

Fissures have

surfaced within the PDM and within member-parties. Some want to play down the

army’s role. While Nawaz and daughter Maryam are blasting the military, his

jailed brother Shahbaaz has called for a “national dialogue.”

The situation

could change with Punjab becoming as the main battleground. Imran could

sacrifice his protégé, Punjab Chief Minister Usman Buzdar, whom he has lambasted

for failing to block the Multan rally.

If Buzdar is

incompetent, critics say Imran is more so. But the fact is a government in

Pakistan has never gone because it was incompetent – it went because army said

enough-is-enough.

Analyst Zahid

Hussain notes that the opposition’s anti-establishment drive has sparked a new

political discourse across Pakistan. People are asking whether a new social

contract is required to rebuild flagging public trust in the state’s

institutions.

On the army-civil

relationship, Ayesha Siddiqa, a political scientist and author of the book

Military Inc tweeted right at the outset, on October 27: “Each party has an

interlocutor with the military but for a meaningful change, PDM parties will

have to start a dialogue with the army that can ensure a meaningful negotiation

of power for the long run.

But short of that,

things need to be done, by the political class, not the military. As Siddiqa

says: “A social contract will have to be much wider. It will have to extend to

smaller provinces but also religious and ethnic minorities. Pakistan has little

chance to become secular but a healing hand will have to be extended to

minorities or else it will remain exploitable.”

For the

foreseeable future, any notion that the army will simply return to the barracks

is naïve. At best, or worst — depending upon the reader’s preference — the ‘laadla’ may be changed.

The

writer may be reached at mahendraved07@gmail.om