Shabana Azmi has many ‘firsts’, like winning five National Film Awards, three consecutively, and six Filmfare Awards. She may be overtaken someday, but being the ‘last’ may never be challenged.

She is the last to grow up in a commune, where she woke up to the chatter of poetry, play, and music that alternated between theatre, cinema, and Marxism-Leninism. That era in India’s political and cultural life ended long ago.

Imagine, called Munni at home, she was given a formal name only when she entered school. Having grown up thus, she went on to study at a Convent school and Jesuit college, into arthouse cinema and then to the boisterous and commercial Bollywood. The daughter of poet-writer Kaifi Azmi and theatre person Shauqat has imbibed the parents’ qualities and passion in abundance.

Her equally illustrious husband Javed Akhtar, son of poet-writer Jan-Nisar Akhtar, also had a commune childhood. But he embraced Bollywood directly, without flirting with the ‘parallel’ cinema. The extended Azmi-Akhtar clan, with many creative people, can be called the new “first family”.

Of them all, Shabana is arguably the most versatile. She has carved a niche in regional cinema, especially Bengali, and has also gone global, in Hollywood and Britain. She is more like Shashi Kapoor of the original “first family”, the Kapoors. Both have promoted and practised ‘purposeful’ cinema. Only, Shabana’s effort, in and outside of cinema, has a political pitch, of the ‘progressive’. Her cue from her parents was that art should push towards change.

Although filmmaking is a team job, critics at home and abroad have noted that several of her films were cited as a form of progressivism and social reformism which offer a realistic portrayal of Indian society, its customs and traditions.

Emerging from Mumbai’s elite Saint Xavier’s College she had access, if not to Bollywood, then to children of Bollywood families among her fellow students. However, she chose to learn the art at the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) and imbibed some Stanislavsky.

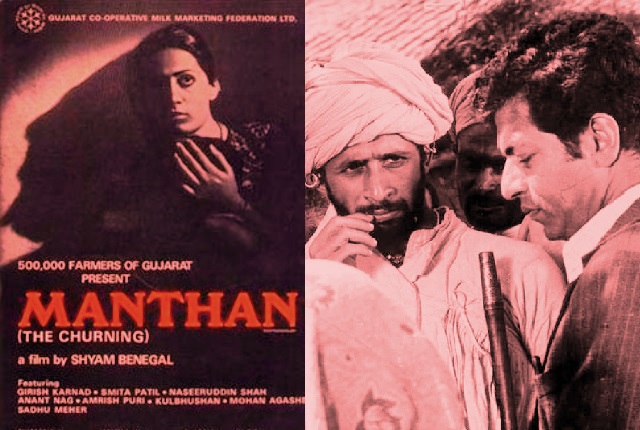

In her first release, Shyam Benegal’s Ankur (1975), the role of a married servant slipping into an affair with a student was risky and was rejected by established actors. Of playing an ‘adulteress’, she said in a recent interview: “I loved the grey shades in Lakshmi’s character. All along, I knew something exciting was going on.”

“Once Ankur was released, it was like a whirlwind. It was selected for the Berlin International Film Festival, in 1974. It gave me my first National Award for Best Actress. Ankur’s commercial success paved the way for other arthouse films. Had I not started my career with Ankur, my career would have been on an entirely different trajectory.”

Call it the lure of Bollywood, and why not? Despite this critical and commercial success in cinema shorn of formula, Shabana also partnered with Amar’s character in Manmohan Desai’s Amar, Akbar Anthony, a typical Bollywood affair. She did not get typecast.

Not ‘beautiful’ in the way Bollywood seeks its heroines, Shabana has a distinct desi charm and poise that convince the viewers. She counsels the newcomers today not try to look glamorous. The face matters.

Besides Benegal and Mannohan Desai, she reached out to Bengal’s Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen and Goutam Ghose who were then accused of “selling India’s poverty” at foreign film festivals. Over the years, straddling Bollywood and Bengal, she did roles immortalized in many Sharatchandra novels, playing the sensitive Bengali with aplomb.

Ray took a while taking her in Shatranj Ke Khiladi (1977) after having spotted her in Ankur: “Shabana Azmi does not immediately fit into her rustic surroundings, but her poise and her personality are never in doubt, and in two high-pitched scenes she pulls out all her stops and firmly establishes herself as one of our finest dramatic actresses.”

Shabana emulated her mother who would dress and act at home to practice her role in a play. A Bombay girl, she has worked hard to depict real-life characters, be it in slums or the countryside, studying and even joining their milieu to achieve a degree of authenticity. In Mandi (1983), to portray the madam of a whorehouse, she put on weight and chewed betel. Real-life portrayals continued in many films. She was Jamini resigned to her destiny in Mrinal Sen’s Khandhar (1984) and a typical urban Indian wife who fought back marital betrayal in Arth (1982) and a mother and homemaker in Masoom (1983).

ALSO READ: Sharmia Tagore – The Graceful Rebel

In Godmother (1999) that brought her the record-setting fifth National Award, however, her accent as a gangster from Gujarat lacked authenticity. Compare her with Supriya Pathak in an identical role in Goliyon Ki Raas Leela Ram Leela (2013) and you see the difference.

The personal gets emotionally enmeshed with the professional. This writer’s favourite is her role as the mother of Neerja (2016), having witnessed events that followed the 1986 terror attack on a PAN-AM flight and the turmoil in the family of senior colleague Harish Bhanot.

Air hostess Neerja Bhanot, killed by the terrorists won everyone’s admiration and sympathy. But an anguished mother Rama Bhanot’s oration at her daughter’s condolence meeting, as she struggled to spread calm, brought tears. “It was very difficult to play her, particularly the last scene where Rama addresses an audience,” Shabana, who won the Best Supporting Actress Award, said.

The arthouse or parallel cinema is now part of our heritage. Having transitioned after playing many powerful women roles, she explains why not many left a lasting impact. The problem lies elsewhere, in the way cinema is made and watched. “If you want change in cinema, it has to come from mainstream cinema. Otherwise, you are preaching to those already converted.”

Selecting roles can be risky. Deepa Mehta’s Fire (1996) depicts Shabana as a lonely woman in love with her sister-in-law. The on-screen depiction of lesbianism (perhaps the first in Indian cinema) drew severe protests and threats from many social groups as well as by the Indian authorities. Portraying the exploited can be exploitative. “Initially, I had my reservations,” she admits. Then she consulted her husband, Javed, who counselled: “If you believe that the film is not exploitative and you would enjoy doing it, then do it.”

Individually and together, the couple have taken up public causes. As lawmakers, they have been more vocal than most from the tinsel town. Javed rallied the Mumbai citizenry after the 2008 terror attacks.

Along with theatre and poetry reading, Shabana has participated in public campaigns against communalism, victims of natural disasters, Kashmiri Pandits, and AIDS victims. She lost in a Lok Sabha election and has campaigned for Left-leaning candidates.

In the present times, social media and not socialism, commerce and not communalism, reign supreme. Septuagenarian Shabana was recently in the news for her peck, in a film, on the cheek of an octogenarian Dharmendra!

For more details visit us: https://lokmarg.com/