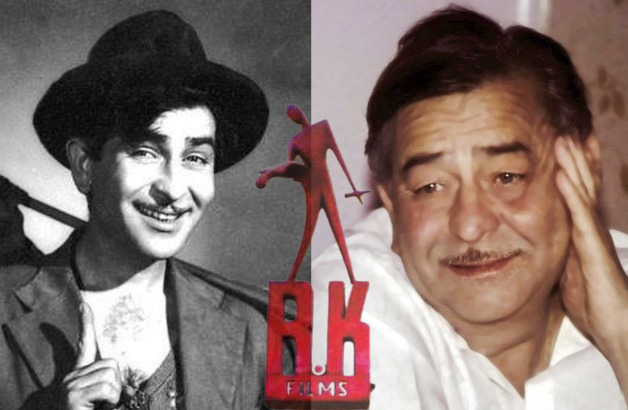

Come December, and last century’s Bollywood nostalgia brims over to this one, connecting with three of its greatest stars. Dilip Kumar (December 11, 1922) and Raj Kapoor, (December 14, 1924) were born near each other’s homes in Peshawar. Dev Anand, born in Shakargarh, passed away on December 3, 2011.

The birth centenaries of Dilip and Dev recently passed, and it is now time to celebrate Kapoor’s. Plus Navketan, Dev’s film production banner, completes 75 years.

The troika’s admirers connect with simpler, if not better, times. Although competing contemporaries, they were also great friends. Generations of cinemagoers they mesmerised love them all but remain divided on who was better, and in which particular film. I recall Raj Kapoor’s pleading with ‘Miss DeSa’ (Lalita Pawar) in Anari (1959) that he is not a thief. Given their distinct acting styles the debate then was: how Dilip or Dev would have delivered the same dialogue.

All three loved music and Dilip sang at private parties. For today’s globalised youth, the two-hour-plus, slow-moving, black & white fare may be boring, but not the Indian Classical-based songs. They were the soul of Bollywood cinema, sometimes surpassing the film and ensuring its success. Music and the ‘Indian-ness’ were the USPs, now lost in the quest to tap the global market.

Compare this with the present-day Indian cinema which is shorter and technologically slick, but an assembly-line product enjoying, unlike in the past, multinational, corporate and bank-driven financing. The majority of them still flop as they used to. The world’s largest producer makes more ‘good’ films, but ‘great’ films?

Hark back to listen to the story “Anand Hi Anand”, about three brothers – Chetan, Dev and Vijay – narrated by their niece, actor-director Sohaila Kapur. She tells you how Chetan’s philosophical ‘filmsight’, Dev’s acting and glamour and Vijay’s prowess as writer-director drove them, together and separately when they disagreed, and pursue new themes and introduce new stars (Kalpana Kartik, Priya Rajvansh, Zeenat Aman, Tina Munim), through hits and flops and financial woes. Few remember today that Chetan’s Neecha Nagar (1946) was the top winner at the first Cannes Film Festival to put Indian cinema on the world’s cinematic map before independence.

Undoubtedly, this month belongs to the centennial of Raj Kapoor, India’s “Greatest Showman”. His family, including current reigning ‘stars’ invited the country’s prime minister to join the celebrations. The PM rightly called Raj the pioneer of “soft diplomacy”, long before that idea took shape, and made the Indian cinema known to the world as both, uniquely Indian and international.

His reference to the change in “Lal Topi Roosi” is politically significant. Surely, it is Hindustani. The Nehru-era colour that immensely influenced Raj’s cinema, has changed. Sadly, the ‘dawn’ that Raj dreamt of in Phir Subah Hogi too, has eluded not only India but much of the world.

As celebrations get underway, word has come from Russia, where Raj was called “Tavarish Brodiya”, of a film festival. Perhaps, China, Central Asia and Central Europe where Awaara retains arthouse interest will follow.

ALSO READ: Awaara – The Tramp And His Times

Time has taken its toll. Raj is quoted as saying in a book by his daughter Ritu: “When I die, bring my body to my studio. I may wake up amid their lights shouting, ‘Action’.” That was not to be. As Bollywood neglected it by shooting indoors and going digital, and engulfed by a fire, R K Studio closed down. Replacing it, the stylish residential complex symbolically retains the studio’s gate and a replica of the iconic emblem – Raj Kapoor holding Nargis with one hand and violin in the other hand – based on a scene from Barsaat (1949). It was RK’s first hit and the first shot in that studio.

So much has already been written about Raj, his films and his filmmaking that repetition becomes inevitable. My only meeting was as a rookie at a film journal. He came unannounced and waited patiently, God knows for how long. I was immersed in work. When I rose, startled and apologetic, he put me at ease with a pat on my shoulder, left a packet for my editor and left.

Before he was conferred the Dadasaheb Phalke award, he was required to clear his tax dues with the government. He sold his films’ telecasting rights to Doordarshan. Too sick to attend, the event had to be postponed four times. He looked drained out that evening. President R. Venkatraman broke protocol, came down from the stage, walked up to him and completed the ceremony. Raj vomited and had to be rushed to the hospital. The man who had made people laugh with Chaplin-like comedy was a sad sight, eyes closed, the garland on him and his jacket soiled.

Youngest of the Troika, he left rather early at 64. Being a producer-director at age 24 with a banner and studio, was audacious. The Anand brothers followed with Navketan a year later.

Like Dev and Dilip, Raj lived in an era when cronyism was not an issue that it is today. Launching relations was a virtue, not a vice. He helped his vast family of Kapoors, Naths and more – probably two scores of them. The fourth generation active today invites the charge of nepotism. But talent is unmistakable. It goes beyond fair skin, great looks and in some cases, blue eyes. The record shows that those lacking this bit have faded out.

In better times, directors under the RK banner included Radhu Karmarkar (Jis Desh Mein Ganga Behti Hai-1960), Prakash Arora (Boot Polish-1954) and Amit Maitra and Sombhu Mitra (Jagte Raho – 1956).

Raj was a Team Man. Nargis, his muse, worked for seven years, till she realised that their relationship would get nowhere. The composer duo Shankar-Jaikishan collaborated for 20 years, till Mera Naam Joker’s failure forced Raj to keep up with the changing time and revamp the team, including the lyricist duo Shailendra-Hasrat Jaipuri.

He helped his PR men, Bunny Ruben and Jugal Kishore Dubey by playing the lead in Ashique (1962). For Shailendra, his poetic ‘soul’, he did Teesri Kasam (1966) which suffered delay and financial crunch. An ageing, rotund, blue-eyed Raj was unlike the poor Bihari the theme required. But he was keen on that role. His performance, with Waheeda Rehman as the perfect foil, however, could not save the film. A commercial disaster, it recovered after winning the National Award to become a cult film.

His films of the 1950s had the distinct leftist touch of KA Abbas when the rich were the villains. In the 1960s and thereafter, he changed course as themes also were varied. But he returned to Abbas for Mera Naam Joker. When this semi-autobiographical multi-starrer flopped, he was devastated. Yet, he gathered himself and at 50, conceived Bobby (1973), about teenage love.

He was accused, with justification, of injecting sexism. He defended it. “We are shocked to see nudity, we need to get mature. I have always respected women but don’t understand why I am accused of exploiting them. Fellini’s nude woman is considered Art but when I show a woman’s beauty on screen, then it is called exploitation,” Ritu quoted her father as saying in the book Raj Kapoor Speaks.

Opinions shall always differ on this, even as Indian cinema, uncensored on OTT, becomes increasingly explicit. And to give Raj his due, the present-day lot need to learn that he was much more than being a Chaplin copycat. And appreciate the “jeena yahan, marna yahan” passion. They are timeless and universal.