‘Har Dil Jo Pyar Karega woh gaana gayega,’ Raj Kapoor sang, linking love with music, in Sangam (1964). That year, his contemporary, Guru Dutt, died, like many characters he portrayed, a tortured soul, at just 39. Yet, the last film he produced, Baharein Phir Bhi Ayengi, released three years after his death, heralded many a hopeful spring.

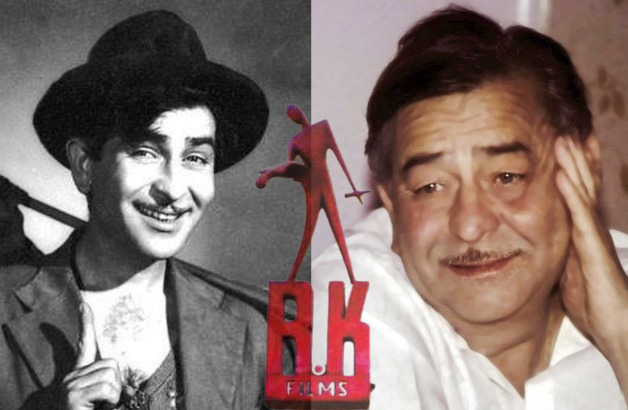

Both, Raj and Guru, were born within a span of a few months. Observing their birth centenaries, it needs noting that nothing, and nobody, has recreated the musical aura that two of Hindi cinema’s most eminent filmmakers created. Their deep understanding of music and its place in cinema has ensured that their films remain watchable and their songs hummable. So, this is more about their music.

Their musical prowess was part of the cinematic cavalcade of giants who contributed to what is fondly called the “golden age”. That newly independent India under Jawaharlal Nehru, despite its many failures, was aspiring and inclusive. Cinema, not just in Hindi/Urdu, reached out to the world with its contemporary stories, even as it told the mythological and social ones.

Today, even if you find the proceedings slow, you wait for the next song, and the next. Recall the little song books costing a single anna (then currency), too shabby for a bookstall and sold only at a paan-cigarette shop? They carried up to a dozen ditties in a single movie.

That music overawed the theme. Its notes carried even a poorly written or enacted film. Every word and note carried meaning. Age-old Hindustani Classical or the Carnatic, went with the Western Rock ’n Roll and a vast array of folk songs from across the country, even mixed with the flavour from other lands.

Often derided as ‘plagiarised’ by the discerning, that musical fusion was unique to India, yet copied by others. They were edited out to reduce the length of the entries sent to international film festivals. But their demand at home never ebbed.

The fare had dollops of ‘dil’ and ‘pyar’, easily the most used words. Although no longer lip-synced by actors, they remain so even as contemporary India grapples with new challenges and sensibilities.

Raj and Guru, both romantics in real and reel lives, embellished their respective products differently. When not chasing or pining for his lady love, Raj sang of hope and nation-building, even mocking the Almighty. Guru’s urban angst against an exploitative and hypocritical society was stark, yet poetic. He criticised the many things that Raj’s songs tended to sugar-coat with socialist ideals, always hoping for a bright future. Vibrantly composed, Raj’s songs playfully helped depart from the terse, sarcasm-laden, in-your-face dialogues written by Khwaja Ahmed Abbas.

ALSO READ: Mohd Rafi – The Baiju Bawra of Bollywood

Unlike Abbas and their other teammates, neither Raj nor Guru was an activist of the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) or the Progressive Writers’ Association (PWA). These two leftist cultural bodies heavily influenced the art, literature and cinema of that “golden age”. Born of political street protests, they influenced storytelling through music.

The poor-versus-the-privileged theme was common. Raj’s “pop-socialism” helped lend a modern touch (“Mutthi mein hai taqdeer hamari, humne kismat ko bas mein kiya hai” (Boot Polish-1954). It helped erase the stereotype about India being the country of sadhus and snake-charmers.

Raj developed a global audience that hummed and danced to “Awaara hoon”. Nostalgia lingers in some societies even today. Compared to that instant bubbly, Guru’s music, like his films, depressed the viewers even while it entertained. It took time, like matured wine, for some of his films to be considered classics. If Raj was popular and very public, Guru’s songs sent the sensitive hearts brooding, privately, perhaps, more intensely.

Of the rich-poor theme, Raj’s song-and-dance with slum-dwellers participating lampooned the rich (Shree 420). Visualise him playing the dafli, spinning it over his head like Lord Krishna’s Sudarshan Chakra, and before the crescendo, bringing it down to remind us of life’s challenges.

By contrast, Guru gate-crashed the party of the rich or a college mushaira (Pyaasa-1957), asking, in Sahir Ludhianvi’s terse words, “Yeh duniya agar mil bhi jaye toh kya hai?”, and before being thrown out, “Tumhari hai tum hi sambhalo yeh duniya”. Never again has protest fused with poetry so beautifully.

Guru’s rich music was a product of the poor, for the poor. There was a song for champiwala (Johnny Walker), and a street hooker (Waheeda Rahman). Kaifi Azmi lived in a commune to pursue politics and poetry. Sahir commanded more prestige than money.

Raj called Shailendra, a welder-turned-polyglot poet, “Kavi Raaj”, who said the most profound things in the simplest words possible. His struggling singer addressed as Mukesh Chand, was “meri rooh” — his soul.

Guru’s poetic protests, penned by Sahir, were set to music by S D Burman, a prince who had quit his royal riches. Together, they heralded without any musical support (Yeh mehlon yeh takhton – Pyaasa), by Mohammed Rafi.

The best example, perhaps, was Kaagaz ke Phool (1959), Guru’s autobiographical opus. The chemistry between him, his singer-wife Geeta Dutt, S D Burman and Kaifi created immortal songs. Kaifi would lament that he rewrote some songs because Guru could not communicate what he wanted. That churning produced some of the best poetry sung in Indian cinema. For the first time, perhaps, it accorded the behind-the-scenes lyricist his rightful place in a glamour-sodden industry.

The overall impact of Kaagaz Ke Phool was overwhelming but depressing. Songs created an aching melancholia. The audience came to be entertained, left the cinema hall depressed, the women in tears. Technologically well ahead of its time, the film flopped, but became a classic of world cinema only later.

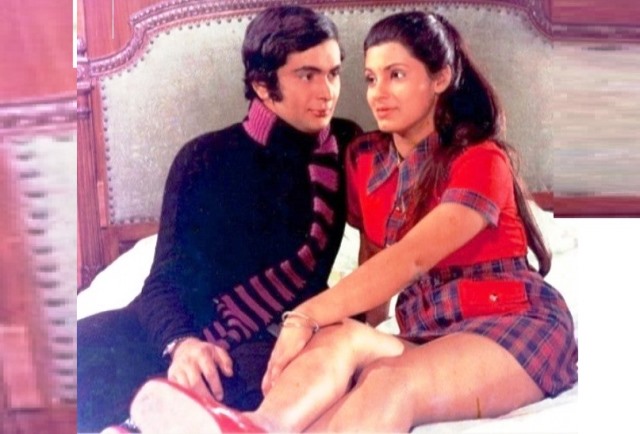

Guru’s classics blurred the lines between personal life and cinema. Though by no means comparable, Raj made the same mistake as Guru a decade later, by making Mera Naam Joker (1970). It bombed despite lovely performances and great music. He recovered only with Bobby (1973), but with music by Laxmikant Pyarelal. His two-decades-plus collaboration with Shankar Jaikishan had ended.

While Raj remained contemporary, Guru explored the decadent Bengal in author-backed Sahib, Bibi Aur Ghulam (1962), helped by Hemant Kumar’s immortal music. Songs of Ravi in Chaudhvin Ka Chand remain best savoured, say, in solitude and an unlit room.

Before he made ‘serious’ films, Guru was a pioneer of the Bombay Noir. Dark and gritty romantic thrillers; they explored crime and corruption in Bombay. Their hallmark was hummable songs, many composed by O P Nayyar. Since it is not possible to continue here about the musical contribution of Raj Kapoor and Guru Dutt, one must end with either Guru’s lament “Waqt ne kiya kya haseen sitam”, or Raj-like philosophy of life: “Jeena isi ka naam hai.”