The best thing one can say about Maharaj, released on Netflix, based on a true story of a libel suit in 1862 about a Hindu priest’s misuse of his temporal powers to exploit women devotees, is to stress its relevance after 162 years.

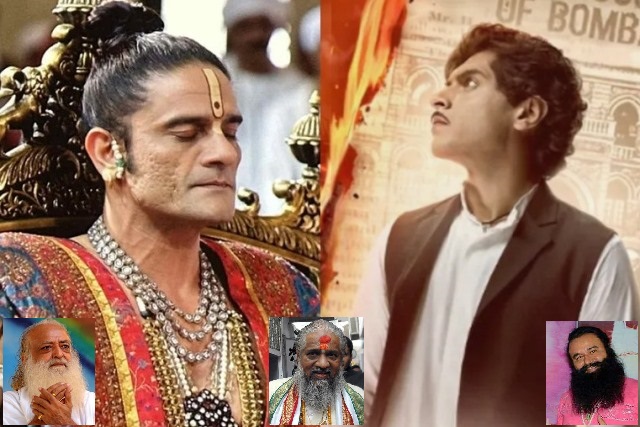

It is a grim reminder of religious and sect gurus mushrooming all across India. Their following thrives even after their conviction for grave crimes, including rape of minor girls, and imprisonment. Of the six listed in the media reports who are either convicted or wanted by law, Asaram Bapu’s plea for suspension of sentence on health grounds was rejected by the Supreme Court on March 1, this year.

Jailed for rape and murder, Gurmeet Ram Rabim of Sirsa, Haryana, gets multiple paroles and furloughs, especially during election time. With lawmakers and ministers coming in their flagged cars to attend and pay obeisance, the collusion with the political class is too obvious to be missed. But it does not stir any protest these days.

Nothing seems to stop people from worshipping humans who act as gods and garner riches and influence and a multitude of dedicated followers. That we are a religious society is a given, but in which other society do such persons thrive? And as an important aside, in which other media, supposedly independent, such people get written/talked about and treated as ‘saints’, ‘seers’, ‘holy men’, ‘godmen’ and more? Criticise them, and be damned – “religious sentiments of the people” are hurt.

Cinema gets away, even if for the sake of mass entertainment, setting examples of good and bad. There was OMG (Oh, My God) in 2012 and some recent films and shows that have portrayed badly behaved spiritual gurus and their brainwashed devotees, including Prakash Jha’s engrossing web series Aashram.

Most of these films are taken to court by supposed devotees or those who enjoy their brief media projection. Political leaders also join in. Besieged with too many controversies, the judiciary respects the Censor Board as the final authority. The Gujarat High Court cleared Maharaj without a cut or caution, while Hamare Barah, a film that alludes to Muslims having too many children and multiple marriages, was allowed to be released with a few cuts.

The Gujarat High Court observed that Maharaj did not target the Vaishnav Pushtimarg sect as alleged by its members who had petitioned against its release claiming that it hurt their religious sentiments. The film has nothing objectionable or derogatory, the court said.

The Maharaj theme developed in the 19th-century tussle between the conservatives who posed as ‘nationalists’ and the British rulers and British education-inspired reformers in many parts of India. It produced the likes of Raja Rammohun Roy. Brahmo Samaj in Bengal embraced a liberal and inclusive theological perspective, drawing inspiration from diverse religious traditions and advocating for religious syncretism. Similar examples abounded in other parts of 19th-century British India. Unsurprisingly, Karsandas Mulji, the journalist-reformer and the film’s protagonist, was mentored by Dadabhai Naoroji.

The film is based on a Gujarati novel by Saurabh Shah, who says that his converting the “Maharaj Libel Suit” into a novel was to stress the issue’s relevance “in the present times in that young women continue to be exploited in the name of religion”, to rekindle the public faith in religion that is shaken when such incidents come to light in the media and the social discourse.

ALSO READ: Devi Bhimji – A Gujarati Who Became Malayalam Media Mogul

Besides public debate, Maharaj has led to scholarly work, including doctoral dissertations in India and abroad. In 2010, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, then the Gujarat Chief Minister, praised Karsandas Mulji’s efforts in promoting women’s rights and social change, highlighting his importance in India’s struggle for independence and social progress.

Besides the exploitation of women perpetuated by the Pushtimarg sect through practices and rituals, the film is about a libel suit. Jadunathji Maharaj, the high priest with his temple located in south Mumbai’s Bhuleshwar, went before the Supreme Court of Bombay, as it was then called. Karsandas claimed that the Pushtimarg was not the “true” Hinduism of the Vedic age, but rather a heretic sect that encouraged devotees to hand over their wives and daughters for the maharajas’ pleasure.

Although secular and working under the Anglo-Saxon jurisprudence, the court took up the case that belonged to the realm of divinity. The bench and the lawyers on both sides were Britons. Several witnesses on both sides, including experts and doctors, were examined. The judiciary was fair and just in commending, and not convicting the journalist-publisher duo. “A public journalist is a public teacher: the true function of the press, that by virtue of which it has rightly grown to be one of the great powers of the modern world — is the function of teaching, elevating and enlightening those who fall within the range of its influence,” said chief judge Joseph Arnould. Jadunath was ordered to pay ₹11,500 to Karsandas Mulji who, incidentally, had spent ₹14,000 in fighting the case. After Maharaj’s debacle, the system of Charan Seva, akin to Devadasi system, that led to female devotees’ exploitation, ended.

Now, the film, its flow and its flaws. Bollywood biggie Aamir Khan’s son Junaid Khan plays Karsandas, a beacon of virtue in a conservative world, advocating widow remarriage and smilingly borrowing chutney from the plate of a Dalit, an ‘untouchable’. His intensely personal motive to rebel against Jadunath and expose his sexual liaisons to the wider public comes from Karsan’s fiance, Kishori becoming one of the priest’s numerous victims. While he is a rebel, she is not. She commits suicide after Karsan breaks off their engagement in disgust. While commending Karsan’s reformist zeal, the court overrides the ‘revenge’ angle.

The bulk of the film is constructed as a battle of attrition between Karsandas (Junaid) and Jadunath, (called JJ by devotees). brilliantly played by Jaideep Ahlawat. A charismatic figure, JJ casts a spell over his flock, preying on the vulnerability and indoctrination of female devotees and exploiting them sexually. Everyone appears to be in the thrall of JJ. Only Karsandas, although a believer and a Vaishnav himself, appears immune, having grown up questioning the superstitious practices of his orthodox sect. He does not question the faith itself or the temple. He is essentially a 19th-century social reformer. Some present-day critics do not find him radical enough but fail to see the continuation of the same practices.

Sadly, despite the Bollywood masala, like raas-garba in a Gujarati setting, the well-meaning Maharaj is a tepid affair. Junaid is unfailingly industrious in that endeavour but is unable to conceal the enormity and extent of the effort that a poor script demands. Perhaps, because he is a debutant, so is the film’s director Sidharth P. Malhotra. Both come across as sincere but have a lot to learn. Junaid, from his father. He doesn’t have Aamir’s baby face. Till the other day, Aamir carried himself as a university lad – with de-ageing make-up and camera techniques.

Maharaj is about one extraordinary man’s fight against a powerful spiritual guru. It is also about an all-out battle between religious manipulation and individual resistance. That makes the effort worthwhile – and as stated at the outset, a good reminder for today.

For more details visit us: https://lokmarg.com/