It’s been nearly a fortnight since India’s election results came out but the feeling of happiness still remains in the air. That feeling, akin to euphoria, surprisingly is not as pronounced among the supporters of those who won in the elections as it is among those who actually lost.

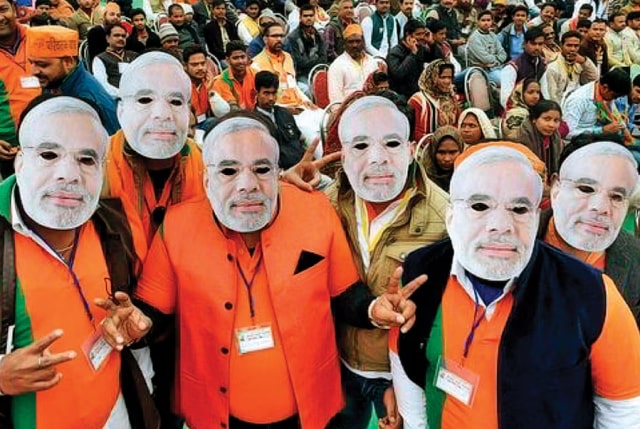

Narendra Modi created history by becoming the Prime Minister again for the third successive term, a feat that we are repeatedly reminded matches India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s three consecutive terms till he died in 1964. Yet on June 4 when the results came out, the Opposition seemed more upbeat than the National Democratic Alliance (NDA), led by Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which, with 293 of the 543 Lok sabha seats, got to form the government. Modi and his party had proclaimed during campaigning that the BJP would win 370 seats and the alliance would cross 400. As it happened, the BJP got only 240 and its alliance brought in another 53. The Opposition and its supporters celebrated a moral victory, pointing out that voters had lost faith in Modi and his party.

Those celebrations and the euphoria may be misplaced. Yes, the Indian National Development Inclusive Alliance (INDIA), a motley electoral front comprising more than 30 mostly regional parties and led by the Congress, won 232 seats; and yes, the BJP did not manage a majority on its own as it had in 2014 (when it won 282) and 2019 (303), but the fact is that in 2024, the BJP and its allies have a more than comfortable majority of 293 seats.

The fact also is that the Congress, which leads the INDIA front and whose leader Rahul Gandhi was perceived as Modi’s challenger in the recent elections, managed a tally of only 99 seats in the polls. It is a big improvement over 2019 when it won a paltry 52 seats and 2014 (44) but 99 is still a small fraction of 543–and certainly not a big reason to celebrate.

Much of the hope, optimism, and euphoria that has spread among Opposition parties and their supporters is because Modi 3.0, as the Prime Minister’s third term has been labeled, is one where the BJP’s allies play a key role in providing the NDA with a majority. Modi’s political detractors point out that some of his key allies, such as Nitish Kumar, who heads Bihar’s Janata Dal (United), N. Chandrababu Naidu, who heads Andhra Pradesh’s Telugu Desam Party (TDP), and Chirag Paswan, who heads Bihar’s Lok Janshakti Party (Ram Vilas), without whose wins in the elections the NDA wouldn’t have had a majority, can be a check on Modi’s government and his style of governance.

Some in the Opposition probably also hope that players such as the JD(U)’s Kumar and the TDP’s Naidu, who have had a chequered past in coalitions, could even pull the plug on Modi and lead to a collapse of the NDA’s numbers in Lok Sabha, causing the government to fall. After all, Kumar has changed his political allegiances several times and, confoundingly, it was he who convened the Opposition’s INDIA alliance last year before ditching it to join the NDA.

ALSO READ: Modi 3.0 Must Focus on Jobs, Rising Inequity

So, will Kumar and/or Naidu pull the plug on the NDA? Many believe both the leaders and their parties could have fundamental differences with the BJP on issues such as the latter’s Hindu nationalist stance, and could, therefore, oppose any Modi 3.0 actions, which could, for instance, be perceived to be anti-Muslim or affect affirmative action for certain underprivileged castes.

Will they really? Probably not. Both Naidu, 74, and Kumar, 73, are in the twilight of their political careers. Like Modi, they share a common hope: of building a legacy. The difference is that while Modi is building a national legacy, Naidu and Kumar are focused on their respective states. At this stage in their careers, the national stage doesn’t beckon anymore.

Instead, both the regional leaders want special category status for their states. A special category would mean that the states get proportionally more central funds for projects as well as other development incentives. Whether they will get that or not remains to be seen but it would not be a surprise if Modi offers them sops so that they remain NDA loyalists and not come in the way of his governance.

Many had thought that in a more precarious coalition government, Modi would have to offer some key ministerial berths to BJP’s allies but that has not happened. The key ministries in his Cabinet are still with heavyweights from his party. So ministries such as home, finance, defence, foreign affairs, and so on have been largely allotted to his trusted party colleagues who ran them in the previous terms.

What the Opposition Must Do

The election results have been analysed to death by now. The thing to remember is that even though the INDIA alliance did well, the major victories for it (and, therefore, the setbacks for the NDA) came because of the performance of the regional parties and not because of how the Congress fared. In Uttar Pradesh, for example, where the BJP suffered a defeat that directly affected its total tally, the Congress had an alliance with the Samajwadi Party but it was the latter that won the most seats by strategically widening it traditional base of Muslims and Yadavs to garner the support of voters from other castes. In Maharashtra, another state where the BJP fared badly, it was the factionalised regional parties and their internecine rivalries that caused the setbacks. In West Bengal, it was to the regional Trinamool Congress that the BJP lost and not to the Congress.

The Congress-led INDIA’s strategy in the elections was mostly reactive. The INDIA parties, including the Congress, did have manifestos, but does anyone recall what they promised? What did they say about ensuring jobs, checking inflation, or tackling inequality? Much of the Opposition’s campaign rhetoric focused either on local issues–not surprising, given that most of the constituents of INDIA were regional–or targeted against Modi and what he was saying during his campaigning.

The BJP’s public campaign, which was single-handedly led by Modi, was focused on his promises about making India the third largest economy in the world; about making India a developed country by 2047; and of playing an even more important role in the emerging global order. Plus, because of his incumbency, Modi could list all of his government’s achievements: infrastructure, social welfare, digitalisation, and so on. Issues such as youth unemployment, inflation, and growing inequality were skirted and even though he gave scores of interviews to the media, “friendly” interviewers glossed over them.

Unemployment and inequality are the two biggest issues that Indians, especially the young, worry about the most. Most of India is young (65% or 910 million are below the age of 35) and youth unemployment is a burning issue, which if not tackled can have serious consequences. So is the issue of growing inequality. A study by the World Inequality Lab in March this year declared that “The Billionaire Raj headed by India’s modern bourgeoisie is now more unequal than the British Raj headed by the colonialist forces.” The study found that during the inter-war colonial period from the 1930s until India’s independence in 1947, the top 1% held around 20 to 21% of the country’s national income. Today, the 1% holds 22.6% of the country’s income.

For the Opposition, restricting the BJP and NDA’s tally in the elections is actually a small beginning of what it could really do: mobilise India’s youth.

INDIA, as mentioned earlier, is an electoral alliance of mainly regional parties. In order to continue to be relevant, these parties should start grassroot movements to organise the youth in each of the regions that they politically dominate. That could, conceivably, become a powerful aggregation of a mass of young Indian voters whose support could be the fundamental base on which INDIA could forge a strategy of being a relevant Opposition in Parliament for now and to fight elections in the future: both at the state level as well as nationally.

Unfortunately, INDIA has shown little signs of such resolve. It is exulting in the wake of its recent electoral gains as if that has been a massive achievement. It has, no doubt, been an achievement: dozens of Opposition parties coming together is a demonstration of how even in a loud, noisy and crowded arena such as India’s, democracy can work. By no means, though, is it a massive achievement. Modi 3.0 will not implode on its own. The BJP’s reduced tally should actually be read by the Opposition as a rallying call to organise itself. Unless it does so, it is INDIA that could face the risk of implosion; not the NDA.