Half a century’s hindsight affords an advantage, though unfair, to view an event with warts and all. The film ‘Bobby’ (1973), opens itself to a critical view, without impacting its popularity, the near-cult status it enjoys and the nostalgia of generations.

So, one begins with a little regret and stating without being judgmental, going only by published records and not gossip and rumours that the film world generates. It may or may not have been the first, but its success set the trend for many things that have become the norm today.

It came when socially and even politically relevant Hindi films, Garm Hawa for one, were being made and would experience release and experience issues, besides production costs. With massive publicity, Bobby’s puppy love story came dressed up as “sublime love.”

Politically, India was in rich-versus-poor ferment. Bobby projected no class struggle. It had two well-off families fighting for their respective pride. But socially, it bridged the religious divide by showing a romance between a Hindu boy and a Roman Catholic girl. Both these phenomena have witnessed massive churning and change in the last 50 years.

But as cinema, after what Bobby did to “Romeo and Juliet”, not officially claimed but touted, the country had to wait decades to witness Vishal Bharadwaj’s Indian adaptations of three tragedies by William Shakespeare: Maqbool (2003) from Macbeth, Omkara (2006) from Othello, and Haider (2014) from Hamlet. No reflection on the filmgoers of those times and these. To each generation its own.

As film writer Bhawana Somaaya records: “When the Sixties ended, Hindi films became increasingly entertainment-oriented and so full of mindless masala, that the Seventies saw a whole movement coming up in rebellion—what is now remembered as the Parallel or Art Cinema movement. This was the time when cinema was clearly divided into Art and Commerce and Middle-of-the-the-Road, and each had its followers.”

Bobby’s success set the trend for debut launches, especially of children of established stars. This is a never-ending debate. Although not the first, Raj Kapoor’s success with Rishi Kapoor was followed by Sunil Dutt (Sanjay), Dharmendra (the Deol brothers) and many more. The Kapoor family itself has four generations. The accusation is that they block ‘outsiders’. But let it be said that only the better ones of both types – and lucky ones, given the uncertainties of filmmaking, film marketing and the audience’s reception – have survived. Given India’s traditional father/mother often transfers legacy to son/daughter, neither the star launches nor the debate for and against them is likely to end.

Certainly not the first or the last, Bobby encouraged the purchasing of film awards. Here, one is going by Rishi Kapoor’s memoir, aptly titled “Khullam khulla”. He confessed to having ‘bought’ an award and was ‘ashamed’ about it. That left Amitabh Bachchan sulking because he was hoping to get it for ‘Zanjeer,’ Rishi said.

“I am sure he felt the award was rightfully his for Zanjeer, which was released the same year. I am ashamed to say it, but I actually ‘bought’ that award. I was so naïve. There was this PRO, Taraknath Gandhi, who said to me, ‘Sir, tees hazaar de do, toh aap ko main award dila doonga.’ I am not the manipulative sort but I admit that I gave him the money without thinking,” Rishi Kapoor writes in his memoir.

ALSO READ: Pakeezah – The Courtesan’s Classic

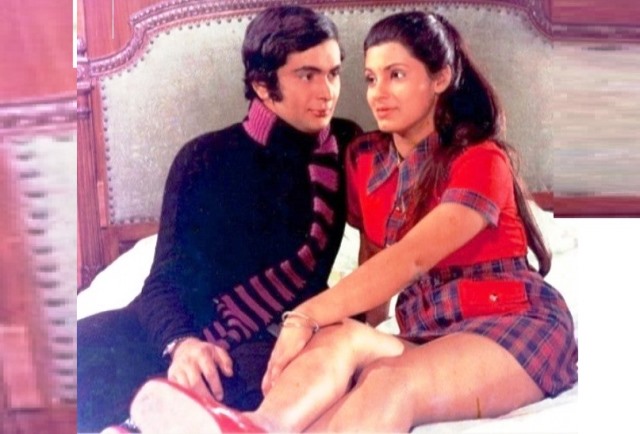

Rishi writes of how his ‘serious’ friendship with a girl ended when Stardust magazine wrote of his ‘romance’ with Bobby’s co-star Dimple Kapadia, although she was married to Rajesh Khanna and was even pregnant before Bobby was released.

Since then, the film paparazzi, like those in politics, business and all other spheres of public activity, have successfully emulated the global trend of digging for information, right or otherwise, at times in connivance with those looking for publicity or to settle scores. The social media has pushed that many times over.

Bobby came when India was socially conservative. People who then experienced their adolescence pangs and pleasures have, at its 50th anniversary (September 28), confessed to enjoying the Rishi-Dimple romance on the screen, keeping it a secret from their scandalised elders. This is universal and timeless – again, to each generation its own. The trend has only been bucked by the fast-spreading culture spawned by not only films but much that is available, at home without going to a cinema theatre, on the OTT (over-the-top) platforms. Significantly, this has bloomed despite the political conservatism currently sweeping India.

Bobby came when Urdu/Hindustani dialogue and lyrics were still the norm in cinema that later evolved as ‘Bollywood’. Not the pioneer again, it set the trend for urbanised Hindi, even the one laced with Konkani spoken by Prem Nath who played a Bombay fisherman. It pushed away the flowery language in which the hero serenaded the heroine.

Bobby’s songs, all of them chart-busters, had a variety ranging from Konkani folk (“Ghey ghey re saheba”), to Punjabi-philosophical folk (“Beshak mandir masjid todo”) to the north Indian (“Jhooth Boley Kauwa Katey”). Incidentally, Raj Kapoor ended his 25-year musical collaboration with Shankar-Jaikishan, switching to another duo, Laxmikant Pyarelal. But while he broke away from Mukesh to have Shailendra Singh sing for Rishi, he had to mend professional fences with Lata Mangeshkar to sing for Dimple.

If the name ‘Bobby’ itself gained wider currency in India, unwittingly, the film was also the forerunner of the present era of brands and branding. A motorbike produced by a family firm related to the Kapoors hugely succeeded when marketed as ‘Bobby’ bike riding on which Raj and Bobby escape their angry parents from Bombay to Goa. Everything from soap to hair clips also sold better with the Bobby tag.

Bobby’s success brought the RK Studios back to life. It launched Rishi’s romantic-hero career and a second one on retirement bringing out the best in him. And Dimple, although marriage and family kept her away from cinema, staged a comeback that is still thriving.

Rishi confirms that Raj Kapoor, already in huge debt after Mera Naam Joker had flopped, needed a life-saver. He did not have the money for Rajesh Khanna, Sharmila Tagore and Mumtaz who were keen to work with him. This proved a blessing. He found an actor from within the family. What the film would have been with the reigning stars of that era, even if successful, would have been run-of-the-mill. We would not have been introduced to teenage love. That makes the film a landmark, no less, in Indian Cinema.

The writer can be contacted at mahendraved07@gmail.com