How does one survive in a world torn between forces for and against globalization? How does one promote mutual acceptance when even bare tolerance is missing? The only answer is cross-cultural communications.

“Bring it at the centre table”, declares retired Indian Ambassador Paramjit Sahai. Cultural exchange, he says, is all about openness and India with its multiple identities within and of the nearly-thirty million diaspora across the globe exemplifies it the best.

His book on Indian cultural diplomacy is for “celebrating pluralism in a globalized world”. Its strength “lies in the tangible way it works. It opens the doors by changing mindset and creating a positive and friendly atmosphere.”

An official representative in many counties, Sahai insists that cultural diplomacy should, however, be essentially “people-centric” and as far as possible, independent. The government should ‘vacate’ areas like films and Yoga that have “come of age” and can be privately handled. He is right.

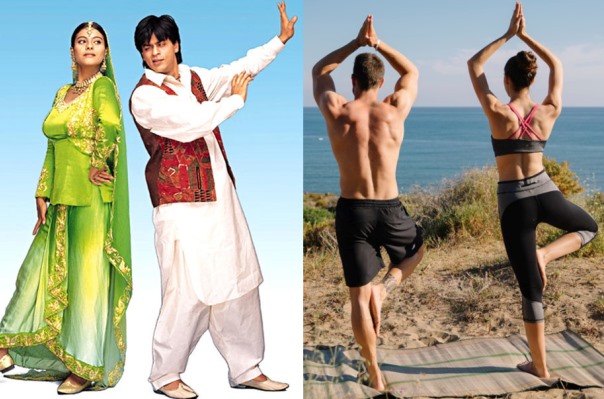

Actually, cinema has for long grown out of Embassy environs into theatres to be savored not only by the diaspora but also local audiences, to become a multi-billion business.

I saw Raj Kapoor’s Awaara (1955), dubbed ‘Chavargo’ in Hungarian language, over four decades back drawing full house in Budapest’s niche theatres. Returning to it in 2016, I found the craze for Bollywood even more, for younger Kapoors, along with the Khans and the Bachchans.

The Japanese some years ago demanded Rajinikanth’s Tamil films underscoring the point that cinema has its own language.

This “soft power” yields hard currency. As much as the difficult to-assess export earnings, Indian cinema exudes a mix of nostalgia and brand loyalty that has sustained for generations and is growing. A big draw among the South Asian diaspora, it has become commercially rewarding, enough for Hollywood production houses to set up shops in India and make it global.

It is amazing but Indian TV serials are popular in distant West Africa. “Everything comes to a halt in our homes at 7.30 PM when they start,” says Richard J A Boateng, a film actor-director from Ghana. So smitten is he by Bollywood that he produced, directed and performed the lead in the first Ghana-India co-production titled Mr. India.

Indian yogis and ‘god men’ have for long thronged the Western world. The Modi Government has extended the Yoga foot-fall on the Thames, on the Danube and with Eiffel Tower forming its backdrop.

Yoga’s global emphasis is on lifestyle, health, restraint, fulfillment and well-being. Some Malaysians debated whether it was okay for Muslims, who are in majority, to perform a “Hindu’ thing that requires chanting ‘Om’. But privately-run yoga centres are thriving.

This “soft power” draws deeply from the past and the present, bolstered by deep cultural ties forged by visitors from and to India. Few other societies can boast of this.

At official level, it is fostered by Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR), the cultural arm of the external affairs ministry. It runs 36 centres across the globe like the one in Budapest, named after Indian-Hungarian painter Amrita Shergill and Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose Centre in Kuala Lumpur.

Cultural diplomacy sometimes rubs off on non-diplomatic spouses. Sahai’s wife Neena has published a delectable book on her experiences, good and not-so-good and how she freely imbibed local art and culture wherever she went.

Another example is Hema Devare. While diplomat Sudhir went about promoting India across Southeast Asia, she explored artworks and textiles in that region, discovering and writing about ancient links with India.

Their scholar-journalist daughter Ashwini has done one better. She grew up changing countries along with parents, describing her quest for self-identity in a book “Lost at 15, Found at 50.”

Ambassador Malay Mishra on retirement is pursuing his doctorate in Hungary, studying Roma or the gypsies, migrants from South Asia, now inhabiting Central Europe.

It is a revelation that Romas or Romanis identify themselves with B R Ambedkar, the Dalit leader who framed India’s Constitution in the last century. Viewed from the human rights prism, Amberkar’s ideas have found echoes among the Romas, 500,000 of whom live in Hungary alone.

In an apparent blowback, the Romas have found connections with Dalits, the socio-economically oppressed Indians, waging their own struggle in the present-day India. Although centuries and hundreds of kilometer apart, they are conscious of their roots even as they struggle to integrate in societies they feel discriminated.

Contemporary India nurtures these ties, albeit in a limited way, helping run schools in parts of Europe and hosting world Roma conferences.

The important thing is that India does not need to be introduced in many parts of the world. But it needs to be cultivated and promoted. One thing the government can do is to follow up the bilateral cultural agreements signed or updated during almost all visits, forgotten at times.

If basic goal is to make friends and influence people, India needs to “catch’em” young, at universities. Here again, the ethos in Indian universities where foreign students come, needs to be radically changed. Colour prejudice against the Blacks from Africa raises the question: is India spreading culture meant only to blondes and whites?

Sahai’s book is set against the backdrop of India’s ethos of ‘Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam’ (The World is a Family) and its pivot is the “Idea of India.” He has a set of questions:

“Can India give the message of spiritualism in a globalized world that is dominated by materialism? Can India lead in sending a message of diversity and pluralism, as lived by it, when the world is passing through a period of divisiveness and hatred?”

“More important than this,” he asks commenting on the present times, “can it retain its own Idea of India, which is coming under strain? While achieving our political goals, we should not lose sight of our ‘Big Picture’ of an India whose strength lies in ‘Unity in Diversity’ and which has been viewed as a benign power.”

Warning against India being seen as a “cultural hegemon”, he lauds the objective of emerging as ‘Vishwaguru’. But says that India should never move away from Sikh faith’s tenth Guru Gobind Singh’s teaching that calls for end to distinction between the teacher and the taught: “Ape Gur, Ape Chela” (He is both a teacher and a student).

The writer can be reached at mahendraved07@gmail.com