China’s and India’s border dispute in Ladakh shockingly spilled over into savage hand-to-hand combat better befitting a Middle Ages scene on 15 June. Yet that bloody confrontation is best viewed within the context of wider Sino-Indian dynamics and in light of aggressive Chinese behaviour in other parts of the world.

Chinese troops wielded steel stakes laced with nails, and clubs wrapped in barbed wire, while rocks were also flung during the hours-long bitter engagement. Many died after falling down steep cliffs and succumbing to freezing water in the river below. It was the deadliest clash on the Sino-Indian border since 1967, more than 50 years ago.

One UK-based expert described it as “an outbreak of lethal violence of unprecedented magnitude since 1967, but it’s been without shots fired.” Antoine Levesques, Research Fellow for South Asia at the UK-based International Institute of Strategic Studies (IISS), spoke to ANI in-depth about the fracas, noting, “The evidence emerging, including on the Indian side, suggests that a degree of preparation by the Chinese played a catalyst role in the tragic events.”

Certainly, in the week from June 9-16, China moved some 200 vehicles into the Galwan area. “Its troops may have prepared the buildup of a coercive position, but with the ongoing contest of narratives between Beijing and New Delhi, it’s either too early or may just be impossible for both public accounts to coincide on the detailed chain of events that led to the bloodshed and questions of causality, let alone responsibility,” Levesques explained.

Yet he sees indications of “a degree of coherence between [China’s] strategic approach to the border and the wider string of tensions on the border … On the other hand, there’s still an element of friction and uncertainty inherent to that particular theatre. Seen from the political capital of New Delhi or Beijing, misunderstandings, miscalculations take place, and there’s a degree, I think, to which the incidents of last Monday show that things can get out of control faster than perhaps both governments expect to be the case.”

Adrian Zenz, a German anthropologist well known for exposing China’s imprisonment of more than a million Uighur Muslims, concurred. He tweeted, “If you look at the litany of excuses and all the downplaying, I am starting to wonder whether that PLA attack on the Indians went further and was bloodier than what Beijing had approved or imagined.”

London-based Levesques continued: “It’s a cautionary tale about how both sides may need more or new provisions within the existing border management regime, to manage miscalculation and friction beyond the latest agreement in 2013 and possible small updates to it since” Furthermore, multiple tensions at different points of the contentious border are bleeding into each other, which may “require new ways of organizing and conceiving of the utility of military-to-military resolution”.

There are numerous speculations about why China has chosen this particular juncture to instigate these tensions at several locations in Ladakh. Levesques believes the tensions are “due to multiple factors on both sides,” although it is difficult to assess China’s. Nonetheless, he pointed out, “The timing is conducive to thinking that China, like other countries, is exploiting opportunities from relative weaknesses of some of its adversaries in the COVID crisis.” For instance, India is now past 90 days into its lockdown.

China appointed Lieutenant General Xu Qiling as the new ground forces commander for the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Western Theater Command, according to a June 5 announcement. Previously he had been the Eastern Theater Command ground commander since December 2018. This would thus seem to represent a kind of horizontal promotion for him, although he is seen as a rising PLA star, and he has now served in all five theater commands.

Could Xu’s transfer to the Western Theater Command be connected to current tensions in Ladakh? Levesques admitted, “It can’t be ruled out.” However, given the PLA’s command hierarchy, he added that “overall it sounds unlikely this factor over-determined China’s actions.”

Henry Boyd, research fellow for Defence and Military Analysis at IISS, told ANI the PLA unit in the Galwan Valley area is the 363rd Border Defense Regiment (unit designator 69316). It is headquartered at Kongka Pass near the Indian post at Gogra/Hot Springs. The unit probably has some 500-600 personnel, but additional forces drawn from parent border defence regiment operational reserves would also have been deployed to the area.

Boyd and colleague Meia Nouwens believe it likely that additional combat forces, in the guise of the PLA’s 6th Mechanized Division, have been deployed as reinforcements. It is headquartered far away on the southern edge of the Taklamakan Desert, but the division represents the Southern Xinjiang Military District’s main operational reserve.

They claimed “companies of main battle tanks and batteries of towed artillery had been deployed at existing Chinese positions north and east of Gogra” by the end of May. Such equipment is consistent with the 6th Mechanized Division’s known assets, as well as with three other divisions in the Xinjiang Military District (4th Motorized Division, 8th Motorized Division and 11th Motorized Division).

Some reports suggest 12 towed howitzers are present in the Hot Springs area, while some Indian media claim Type 88 tanks are also present. However, most satellite imagery viewed by ANI is of insufficient resolution to identify armoured vehicle types.

Perhaps 5,000 additional troops have been diverted to the area in support of regular border regiments. Interestingly, Indian reports suggest that those Chinese troops involved in the brawl on 15 June had replaced the usual border troops. The introduction of fresh troops, who had no affinity or relationship to the Indian side, may have been a deliberate PLA ploy to foster greater aggression.

Yet Levesques reminded ANI of the true purpose. “This is not geared towards a showdown and warfighting. This appears primarily intended for tactical deterrence and coercion below the threshold of actual use.”

Yet the explosion of violence has serious implications for Sino-Indian relations and the border in general. Levesques highlighted three implications. “One is that the border and its management regime, which both countries have built patiently and vowed to abide by, really cannot be air-gapped from the cooperative elements of the relationship between the world’s two largest emerging markets. So if something goes seriously wrong on at the border, it’s very difficult to make sure it doesn’t contaminate the rest of the relationship. It’s not a new lesson, but I think it’s been brought to the fore with a lot of force this time.

Indeed, he speculated that the border management regime is “at risk of being made out of date, because it is rests on the idea that single incidents can be addressed through talks because their cause is a local problem well short of bloodshed, only related to 23 so-called ‘areas of differing perceptions’ on the LAC, which can be over 25 kilometres deep”.

“Second, it’s harder to insulate the border developments and attribution of Chinese behaviour on that border from the wider territorial contests taking place elsewhere in Asia and also involving China.” Indeed, some analysts see similarities to what China is doing in the South China Sea. Levesques said for a long time “it was assumed the border had its own dynamic, grammar and rules of engagement, and those were largely immune to the wider change in Asia. People now arguing this are in a small minority in India, and an even smaller one other than in China.”

The third implication: “Both sides’ political control of border tensions is now lessened because the reading of any incidents there is no longer just set in that narrow, bilateral, theater-specific context. Instead, it is being read in the context of a very wide Indo-Pacific geostrategic chessboard stretching from California to East Africa. This may bring opportunities for diplomatic trade-offs but it is going to make standoffs, including the one we’re currently still witnessing, more difficult to read as geographically discrete events and to solve as such. And it will be more difficult to read intent in any of those on either side, because suddenly it’s tempting to read this solely through a crude Indo-Pacific prism: one in which India is a global geopolitical swing state and on-shore Asian balancer which China would have risked irking into siding structurally with the US and many of its partners. The correct future reading of border events will likely be somewhere in the middle, but likely not exclusively on either end of that spectrum only.”

It is known that 20 Indian soldiers died, but it is difficult to assess the number of deaths on the Chinese side. Beijing steadfastly refuses to delineate casualty numbers, although they definitely did occur. Hu Xijin, the hawkish editor of the Global Times, wrote patronizingly, “Based on what I know, Chinese side also suffered casualties in the Galwan Valley physical clash … Chinese side didn’t release number of PLA casualties in clash with Indian soldiers. My understanding is the Chinese side doesn’t want people of the two countries to compare the casualties number so to avoid stoking public mood. This is goodwill from Beijing.”

In actual fact, it is normal Chinese practice never to release official PLA casualties, at least not until decades later. M. Taylor Fravel, professor of political science and Director of the Security Studies Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, pointed out, “I can think of no armed conflict involving China where it has released casualty figures publicly at the time of the conflict. Usually, they are published years or decades later. Casualties from 1962 war only published in 1994 internal history.”

With Indian media claiming anywhere from 35-43 Chinese casualties, including the commanding officer, Hu posted on social media platform Sino Weibo, “Finally, I want to say to netizens again, please trust our government and the PLA’s ability to deal with border issues. Don’t listen to any rumors about the number of casualties from abroad.”

ANI has not observed any credible figures for PLA casualties on Chinese social media. However, informed government sources in India have confirmed to India a total of 43 PLA casualties (dead or injured) and increased helicopter evacuations witnessed in the Chinese side of the LAC post the bloody clash of June 15. Those in the know would be too fearful to release such sensitive information. Interestingly, Chinese media have deliberately been downplaying news of border tensions. On the day following the clash, the People’s Daily and PLA Daily did not mention it at all, whereas the Global Times Chinese edition relegated it to p.16.

Nonetheless, the border conflict trended quickly on Weibo on 17 June. It was the fifth-top topic that day, with more than 1.34 billion posts using the hashtag “China-India conflict”.

Comments from Chinese officials have been sporadic. Senior Colonel Zhang Shuili, the spokesperson for the PLA’s Western Theater Command, blamed India on 16 June for the melee. Zhao Lijian, Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesman, has given the longest official response yet. China is also wheeling out proxies such as academics, all invariably blaming India.

Asked why China has been so quiet on the topic, Levesques referred to China’s traditional public diplomacy to India which “emphasizes cooperation, face-saving and minimizes disagreement”. He added, “For China, India matters more and more, both as an opportunity and challenge, but China still has often more pressing or important foreign policy priorities to attend to, not least US-China matters.”

Furthermore, he pointed out that saying less publicly means you can pass on messages in a less ambiguous manner through diplomats, experts, private networks and other means.

Who, then, has benefitted from the current tensions so far? Levesques assessed, “I think any tactical military advantages China may have sought are much less significant than any gains it may have made strategically. The reason for that is that patrolling new swathes of territory – there are reports of 60km2 of territory essentially being captured by the Chinese side in the last month or so – is really only critical militarily if there’s ever a much wider conventional conflict, which neither side otherwise wants as nuclear-armed states. Otherwise, such moves are expressions of political-military resolve with domestic political implications, as well as foreign strategic ones.”

Thus, the South Asia specialist believes this is all part of a political contest. “This is chiefly a political-strategic contest; much less a military one. India and China are aware of the national power differential between them in the latter’s favour.”

Regardless, if China continues occupying the territory seized, there are on-the-ground advantages. Nathan Ruser of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute commented, “Strategically, the PLA’s advances into the Galwan River Valley provide a superior vantage point for observing a supply route used by the Indian Army to reach its northernmost base, and the world’s most elevated airfield, Daulat Beg Oldie. From ridgeline positions, PLA forces would be able to monitor all traffic on the recently completed Darbuk-Shyok-Daulat Beg Oldie Road…”

At Pangong Lake, China has inserted troops between Fingers 4 and 8. Ruser observed: “Significant positions have been constructed between Fingers 4 and 5, including around 500 structures, fortified trenches and a new boatshed over 20 kilometres farther forward than previously … The scale and provocative nature of these new Chinese outposts are hard to overstate: 53 different forward positions have been built, including 19 that sit exactly on the ridgeline separating Indian and Chinese patrols.”

The seriousness of 15 June’s fatal encounter cannot be understated, but it all matches typical patterns of Chinese behaviour, which some call salami slicing.

Levesques commented, “The Chinese patrolling on its side of the Line of Actual Control [LAC] has been assertive for many years. The Chinese military has been building its infrastructure to high standards, and we can expect that to continue, with India mirroring this What is perhaps new in this instance is that China may no longer just be pushing its patrolling to its own understanding of where the LAC is, up to its claim line. India has rejected what it sees to be China’s new claim over the entirety of the Galwan Valley. It is the novelty of that claim, since the war, which worries India.”

China and India are rightfully proud that their troops have not fired a single bullet at each other across the LAC in more than four decades. Yet this confrontation is a diplomatic game-changer for their relationship.

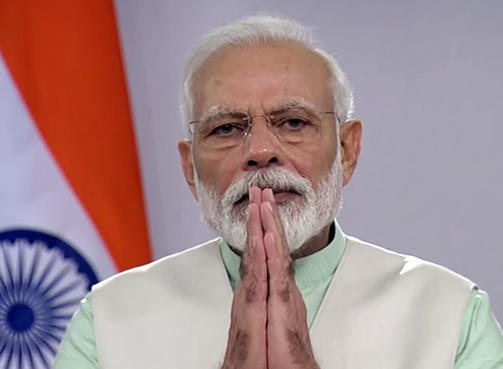

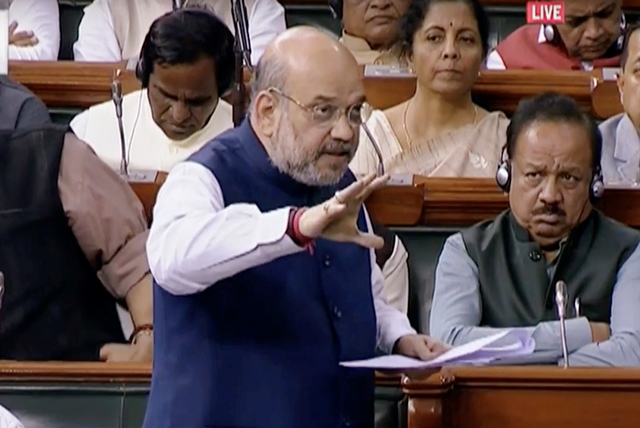

Levesques believes, “It’s hard to see how diplomatic practice as we’ve seen since autumn 2017, at the very least, can continue.” Therefore, a third Xi-Modi informal summit is unforeseeable in the short-to-medium term, and the two special representatives Ajit Doval and Wang Yi will have to play even greater roles.

The IISS expert concluded, “What started in May is not over. It’s going to continue and we shouldn’t see this yet as a closed incident … The 2017 stand-off lasted officially 72 days; that was without any loss of life. The more clement weeks of the year in the Himalayas continue.

“But while both sides emphasize keeping a robust resolute defence stance at and beyond their border, they signal keenness to avoid military escalation on the border, if not elsewhere too. Whole-of-government diplomacy, involving both diplomats and soldiers, is playing an important role in this regard. But diplomacy is not yet able to resolve the current tensions, let alone the wider border dispute.” (ANI)