The “Bass Bomb” that exploded

last week may not damage the Americans, even Indian Americans, as they prepare

to vote in the United States’ presidential elections, come November 3, when incumbent

Donald Trump has staked his all for a second term.

The ‘bomb’ is in the shape of

confirmation of what is known about how the American leadership of 1971 –

President Richard Nixon and National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger – enforced

their ‘tilt’ against India and favouring Pakistan, fully aware that the latter

was ‘cleansing’ East Pakistan of ‘rebels’ who had voted overwhelmingly against

the west-wing.

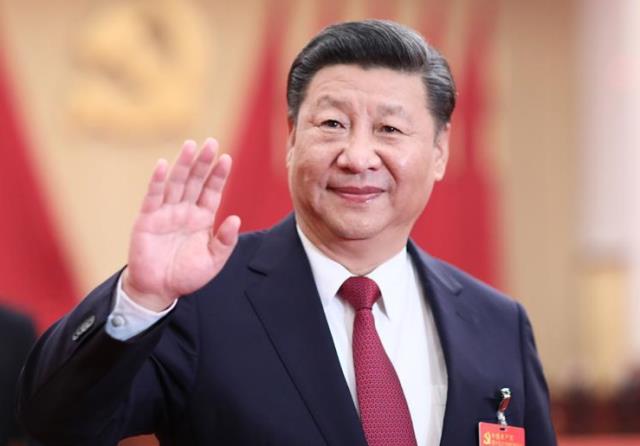

The duo thought India had

contrived or encouraged the flow of ten million-plus refugees. With China

factor looming large – Pakistan had facilitated the reach-out to Beijing – the two

condoned one of the grimmest man-made disasters, and invited their own

diplomatic one, that the last century’s cold war had witnessed.

What is new are official details

contained in White House tapes, now declassified and acquired by Prof. Gary J

Bass of the Princeton University. They unmistakably paint the two in darkest

colours. As they worked their South Asia policy, they frequently engaged in

racist remarks and misogyny targeting Indians in general, especially then Prime

Minister Indira Gandhi, calling them names.

What we know are the

un-bleeped, or less-bleeped taped conversations. Should one be surprised at

Trump’s racism and misogyny (he is not alone) in the current electoral

discourse? It shatters the image the Americans and their successive leaderships

have wanted to cultivate of them being the world’s greatest democrats.

The Bass confirmations,

rather than revelations, may not impact Trump who may win. Analysts who predict

this, in the same breath, disapprove of him and his policies. They point to his

improving his position in the presidential race precisely for the type of racism

and misogyny that his peers had engaged in the 1970s.

Analysts predict a likely Trump

victory even as they criticise his turning a thriving economy into a jobless

one and his handling of the Coronavirus pandemic that has killed more Americans

than the two World Wars. Not just the Americans, much of the world today is witnessing

strange times, of being ruled by right-wing demagogues.

It would thus be naïve to

think that the American voter will be influenced by a diplomatic disasters that

occurred nearly half-a-century back. As elsewhere, foreign policy does not impact

American elections.

Equally, the Indian American numbers

matter but marginally, be it for partly-Indian Kamala Harris, the running mate

of Trump’s Democratic rival Joe Biden, or for Trump who did make a bee-line to

India, especially Gujarat, being hosted by Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

While showing Americans the

mirror, Bass’ account painfully reminds of the Americans’ low esteem when the Indians’

rush to California was gathering momentum in the 1970s and even later, in the

1980s. They can look back with some satisfaction of having done well in the

last three decades. Whether they will retain their traditional Democratic preference

or vote with “Howdy Modi” will need watching.

Of course, India is no longer

the US’ Cold War adversary. Four million Indians, many of them prosperous and

many related to India’s policy-making elite, enjoying visa preference over

others, study and work there. The two are tied in a strategic partnership that

has significantly altered geopolitics of the region well beyond South Asia.

For Indians at home, who have

seen many American presidents and many premiers of their own, the “Bass bomb”

could revive a measure of anti-American feelings. The Indian political class of

that era, it needs reminding, was united in its criticism of the US and had wholeheartedly

welcomed Bangladesh’ emergence. Atal Bihari Vajpayee, at least, had called

Indira goddess ‘Durga’. The argumentative Indian was never so united – and never

since.

The Bass account draws a

positive picture of Indira when the Congress party she once led is at its

lowest and she and her entire family are being systematically vilified. Will the

party want to dwell on her 1971 role, and to what effect, in the face of the hostile

Modi/media/middle class juggernaut?

Did Nixon-Kissinger know enough

Indians before calling them, among other names, ‘bastards’ and wondered how Indian

women “sexless and pathetic people reproduce in large numbers?” Kissinger

called Indians “superb flatterers” whose “great skill” was to “suck up to

people in key positions”. It is not worth exploring.

Some explanation for their

personal peeves and prejudices is, however, available from the account of

Maharaj Krishna Rasgotra, whom Indira sent as envoy to the US and was later

India’s Foreign Secretary. He had met Kissinger in 1969 in the first few weeks

of reaching Washington.

In his 2016 book A

Life in Diplomacy, he quotes Indira as saying before posting him:

“Richard Nixon means trouble for India. He dislikes India and he hates me.” The

‘hatred’, it turned out, was mutual.

For Nixon and Kissinger, often

used to dictators grovelling at their feet – Pakistan’s General Yahya khan was

a ‘friend’ — “it was a novel and unpleasant experience to be defied by an

Asian leader”, one who led the world’s largest democracy. “In their

frustration, Nixon and Kissinger heaped insults and abuses on the Indian prime

minister,” writes Rasgotra whose overall worldview shows no anti-US bias.

How did Indira respond? “She

bore all that with unwonted sang froid, but left no doubt in her talks with

Nixon in 1971, that Pakistan’s pushing ten million of its nationals into India

was tantamount to an aggression on her country and would be dealt with as such.

She ignored their threats of aid cuts and made it clear that if the US were to

embark on a course of hostility, she would live with that too and explore other

options.”

Although India received food

under American Law PL480, it was no ‘Banana Republic’. Mind you, by that time

in August, India had already signed the Peace and Friendship Treaty with the

Soviet Union. The US was blind to its likely implications. Nixon relied on Kissinger’s

doctrine about establishing ‘linkages’ of bringing in China if Pakistan was in

trouble. That never happened. Today, when Pakistan’s economy is dovetailed into

Chinese, Trump wants to ‘help’ India against Chinese border incursions. Times

have changed.

Rasgotra recalls: “Henry knew

(and so did President Nixon) that their policy was in shambles. There were

rumours in Washington that Dr Kissinger was in a state of deep depression and

that for three or four days, even President Nixon had shunned him.”

Till she lived, Indira never

uttered a word about the duo’s ill-treatment. She showed what she and India

could do in December 1971. She is no more. Nixon, who had to leave the White

House in disgrace over Watergate Scandal, is dead.

Kissinger is around. He has

repeatedly apologised. He has visited India and interacted with Indians. Hopefully,

he has changed his views of them. Even Bass records that Kissinger may have

just echoed Nixon’s prejudices probably without really believing in them.

Rasgotra, who admires

Kissinger – nonagenarians both, he is a year younger — records that the latter,

at one of their meetings, insisted that he was “not anti-India”. “I let that

pass,” Rasgotra concludes.

The

writer can be reached at mahendraved07@gmail.com