Yoga, now a world phenomenon that started some 5,000 years ago in the Indus-Sarasvati civilization in Northern India, is today, found in all corners of the globe and most commonly found in bougie studios in major cities in North America and Europe.

In the 5th century, yoga was meant for meditation and religious use, but not as a form of workout. At around the same time, the concept became even more established among the Jains, Buddhists, and Hindus. The first versions of yoga were meant for spiritual practices and revolved around several core values we will discuss below.

A brief history of yoga

Though it appears no one has been able to pin down an exact date as to when the practice of yoga originated, due to its oral transmission of sacred texts and the secretive nature of its teachings, and the fact that the early writings on yoga were transcribed on fragile palm leaves that have inevitably been damaged, destroyed or lost. There is evidence that yoga practice originated during the Indus-Sarasvati civilisation in Northern India over 5,000 years ago in pre-partition India (South Asia), though some researchers think that yoga may be up to 10,000 years old.

Typically, when discussing the timeline of yoga, it has been split into four sections: pre-classical yoga, classical yoga, post-classical yoga, and the modern period.

Pre- Classical Yoga

The word yoga is believed to be first mentioned in ancient sacred texts called the Rig Veda. Vedas are a set of four ancient sacred texts written in Sanskrit. Therefore, the Rig Veda is the earliest among all four Vedas and is an assortment of over a thousand hymns and mantras in ten chapters known as mandalas.

Yoga was slowly refined and developed by the Brahmans and Rishis (mystic seers) who documented their practices and beliefs in the Upanishads, a huge work containing over 200 scriptures. The most renowned of the Yogic scriptures is the Bhagavad-Gîtâ, composed around 500 B.C.E. The Upanishads took the idea of ritual sacrifice from the Vedas and internalized it, teaching the sacrifice of the ego through self-knowledge, action (karma yoga), and wisdom (jnana yoga).

Yoga is amongst the six schools of philosophy in Hinduism and is also a major part of Buddhism and its meditation practice.

Classical Yoga

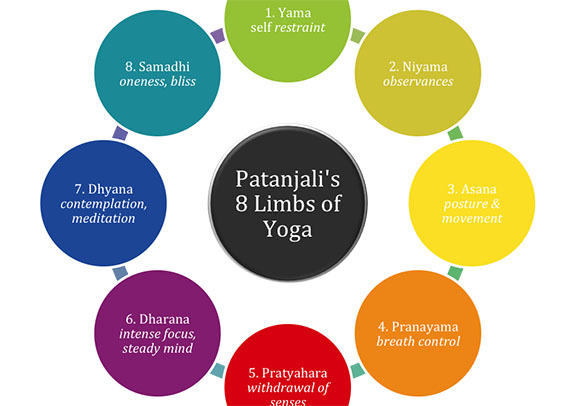

While in the pre-classical stage, yoga was a collection of various ideas, beliefs, and techniques that appeared to conflict and contradict each other, the Classical period is based around the definition provided by Patanjali’s Yoga-Sûtras, the first systematic presentation of yoga. Written in and around the second century, this text describes the path of Raja Yoga, often called “classical yoga”. Patanjali organised the practice of yoga into an “eight limbed path” containing the steps and stages towards obtaining Samadhi or enlightenment. Patanjali is often considered the father of Yoga and his Yoga-Sûtras still strongly influence most styles of modern Yoga.

Post-Classical Yoga

A few centuries after Patanjali, yoga masters created a system of practices designed to rejuvenate the body and prolong life. They rejected the teachings of the ancient Vedas and embraced the physical body as the means to achieve enlightenment. They developed Tantra Yoga, with radical techniques to cleanse the body and mind to break the knots that bind us to our physical existence. This exploration of these physical-spiritual connections and body centred practices led to the creation of what we primarily think of yoga in the West: Hatha Yoga.

Modern Period

Modern Yoga as it is known in the West took off in the late 1890s when Indian monks began spreading their knowledge to the Western world for the first time. Moreover, people who travelled to India were able to rub shoulders with the yogis and observe their practices first-hand.

The introduction of Yoga to the West is often credited to Swami Vivekananda, the first-ever Indian monk to have visited the Western world. Vivekananda (born in 1863 and died in 1902) organised numerous world conferences on the subject by describing yoga as a science of the mind. He translated Yogic texts from Sanskrit into English and in 1893, during a visit to the US, sparked the nation’s interest by demonstrating Yoga poses at a World Fair in Chicago. As a result, many other Indian Yogis and Swamis were welcomed with open arms in the West.

In 1920 Paramahansa Yogananda came to address a conference of religious liberals in Boston. He had been sent by his guru, the ageless Babaji, to “spread the message of kriya yoga to the West.”

In 1924 the United States immigration service imposed a quota on Indian immigration, forcing people like Theos Bernard to travel to the East to seek teachings. He returned from India in 1947 and published Hatha Yoga: The Report of a Personal Experience, an important text for yoga in the 1950s which is still read today.

As early as 1950, many associations and federations dedicated to yoga were born in all countries of the world.

Richard Hittleman, after studying in India, returned to New York in 1950 to teach yoga. Not only did he sell millions of copies of his books and pioneered yoga on television in 1961 but was the first to introduce a nonreligious form of yoga for the American mainstream, with an emphasis on its physical benefits.

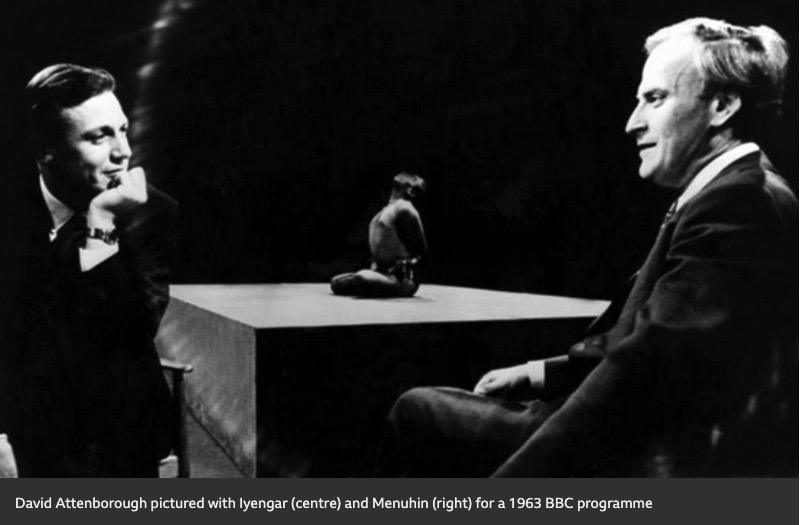

BKS Iyengar is widely regarded as one of the most fundamental figures in the spread of Eastern spiritual philosophy across the world. He introduced Yoga to the western countries by amazing television audiences with his incredible physical suppleness in America and the UK. In 1963, he appeared on the BBC with David Attenborough and violinist Yehudi Menuhin. Time magazine even named him one of the 100 most influential people in the world in 2004.

In India, Sri Krishnamacharya (born in 1888 and died in 1989) enabled Hatha Yoga to take the form we know today (it was formerly rougher). Krishnamacharya went on to create his own yoga school in his native country (where he stayed until his death). After his passing, it was his son, T.K.V. Desikachar, who contributed to the development of this form of yoga throughout the world.

A 1965 revision of U.S. law removed the 1924 quota on Indian immigration, opening our shores to a new wave of Eastern teachers a flood of Eastern teachings to the West. By the ’70s you could find yoga and spiritual teachings everywhere.

Obviously, between traditional yoga and modern yoga, practices are no longer quite the same.

Today

Yoga is for people of all ages and physical abilities.

Over time, different forms of yoga have developed to meet the needs of everyone.

The best known are:

- Vinyasa Yoga

- Dynamic Yoga

- Ashtanga Yoga

- Yoga Nidra

- Kundalini Yoga

- Iyengar Yoga

- Prenatal Yoga

- Karma Yoga

- Natha Yoga

- Bikram Yoga (also called Hot Yoga); Etc.

Ideal for stress and pain (back pain, for example), every yoga session is usually divided into different phases:

- Relaxation

- Breathing exercises

- Stretching

- Meditation

- Yoga poses work the body’s flexibility (such as sun salutations)

- Recitation of mantra.

How the West has turned yoga, something you can do for free, into a multibillion business?

Today 300 million people are practicing yoga around the world, and in 2020, the global yoga industry was valued at around 40 billion dollars.

Perhaps inevitably, yoga’s journey from ancient spiritual practice to big business and premium lifestyle — complete with designer yoga wear, mats, towels, luxury retreats, and $100-a-day juice cleanses — has some devotees worrying that something has been lost along the way.

The growing perception of yoga as a leisure activity catering to a high-end clientele doesn’t help. “The number of practitioners and the amount they spend has increased dramatically in the last four years,” Bill Harper, vice president of Active Interest Media’s Healthy Living Group, told Yoga Journal. More than 30 percent of Yoga Journal’s readership has a household income of over $100,000. As American yoga master Rodney Yee remarked at a 2011 Omega Institute conference, compromising the authenticity of the practice and ignoring its traditions is “ass-backwards.” “It dumbs down the whole art form,” he said.

Julia Gibran is a Toronto yoga teacher of Indian descent. When asked whether she felt much of Western yoga can be boiled down to cultural appropriation, she said, “Of course it is.” But Western yogis, she says, can reduce the harm of their behaviour by being aware of the roots of the practice, and by giving credit where credit is due.

Parting thoughts

We are “taking the gifts of the ancestors without a commitment to their descendants”- Starhawk. This is very much something that people who practice yoga should be aware of. While yoga can and should be enjoyed by all, there should be a strong recognition of its history and ancestry.

Through practicing yoga, it is important we honour the traditions and history- this includes supporting and standing in solidarity with the culture and people from whom this wisdom originates.