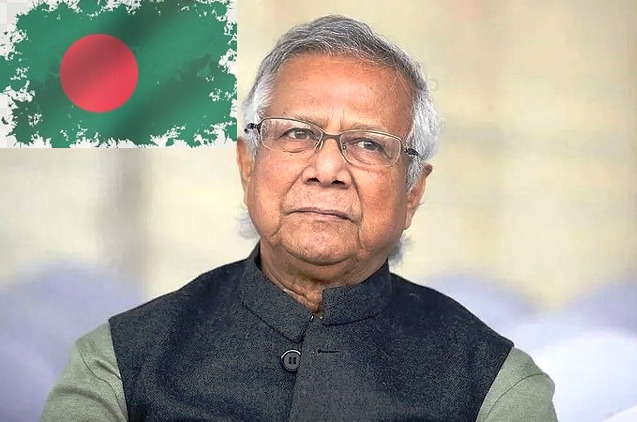

Muhammad Yunus, chief adviser to the interim government of Bangladesh, who acquired global reputation based on promotion of microfinance, targeting women through Grameen Bank, is facing multiple challenges in his unexpected new avatar. For him to push political reforms and steering the economy through turbulent times will require of Nobel laureate Yunus to maintain cordiality with India, China and the US as well as maintain peace in the country by disciplining the students and not allowing extremist forces, including Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami and ISI sympathisers (their growing influence remains a cause for concern) to influence policymaking.

Once in the past, in 2006-07, Yunus following his fallout with the then prime minister Sheikh Hasina started dabbling in politics, including proposing constitution of a political party to be named Citizens’ Power. But the effort was abandoned soon because of perceived lack of support among the people. The announced philosophy of the still born party being “secularism and social liberalism” and politically positioned “centre to centre-left,” one gets a fair idea of which way Yunus will like Bangladesh to move, in case he gets a free hand, unbothered by the army and two student representatives (Nahid Islam and Asif Mahmud) in the interim government.

Yunus was seen as somebody, who based on his past work in the country from giving women economic independence that changed their standing in the family and society to ushering in mobile telephony, ideal to heal the wounds on the body politic. While Yunus is man of the moment, he has to contend with several power centres, including the army. In the circumstances, many of the reforms that he may want to introduce before the general elections are held may undergo dilution because of pressures from vested interests, many inimical to India and favourably inclined to Pakistan. What in any case remains a concern even after the overthrow of Sheikh Hasina government over three months ago is the general disorder and regular circulation of rumours, causing fear and confusion among sections of the people.

Hasina government will be faulted on many counts, including muzzling of the opposition political parties and curbing freedom of the press and airing of criticism by civic society. But Hasina could claim credit for the country’s economic progress, particularly strengthening of the infrastructure and breakthroughs in agriculture that the country made under her watch. From a dangerously food deficit country and critically dependent on imports, Bangladesh is now a net exporter of a number of agri products. Let that progress in the farm sector (agriculture, forestry and fishing), accounting for about 12 per cent of GDP and providing employment to approximately 43 per cent of workforce be not derailed by prevailing uncertainties.

Sources in the caretaker government say the proposed reforms to clean the system will take time and therefore, the parliamentary elections will have to wait till early 2026. But such prevarications about the election schedule are much to the dislike of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), which want the reforms to be carried out expeditiously preparing the ground for holding elections. Reforms apart, the caretaker administration cannot be oblivious to the UN General Assembly giving Bangladesh the target to graduate from a least developed country to a developing country by 2026 end. No doubt, the present circumstances are hardly propitious for taking a few more steps forward to reach that coveted target. In case the country returns to a functioning democracy, then that journey will become easier.

Back in 2016, Yunus subject to unrelenting harassment with all kinds of accusations, including a usurious moneylender, violator of labour laws and misuse of funds of the organisations he led could not think in his wildest dreams of leading the country at any stage. Therefore, as freewheeling liberals are prone to doing, Yunus spilt vitriol on Donald Trump at a meeting in Paris immediately on his winning the presidential election for the first time. Yunus then said: “Trump’s win hit us so hard that this morning I could hardly speak. I lost all strength. Should I even come here? Of course, I should. We must not allow this lapse into depression. We will overcome these dark clouds.”

ALSO READ: Bangladesh Regime Change – What Lies Ahead For India

But as things turned out, Yunus became chief adviser of Bangladesh, where anarchy prevailed and rule of law was at a discount, in August and Trump will now be on his second presidential term. Trump couldn’t have cared what Yunus thought about him. He in any case gives the impression that scurrility hurled at him didn’t bother him then and also now. What, however, is certain is that such airing of views, though well in the past, is not to go down well with the US Administration. It is believed that Grameen America and Grameen Research made handsome donation to the Clinton Foundation ahead of Hilary’s bid for US Presidency. That also will not be a brownie point for Yunus vis a vis the Republican Administration.

In any case, Yunus who is close to the Democratic Party and hoping to secure a favourable financial package had Kamala Harris won the election must have been rattled by what Trump said ahead of the poll in a Diwali message. Describing Bangladesh remaining in “a total state of chaos,” Trump said: “I strongly condemn the barbaric violence against Hindus, Christians and other minorities who are getting attacked and looted by mobs… It would never have happened on my watch. Kamala and Joe have ignored Hindus across the world.” What likely added to Yunus discomfort was Trump describing prime minister Narendra Modi as his “good friend.”

The Trump missive has brought some comfort to the Hindu community in Bangladesh, which for no reasons paid dearly in terms of lives lost and property destruction during and after the mass uprisings to remove Sheikh Hasina government from power. The 13.1 million Hindus constituting 7.95 per cent of the total 165.16 million population are the single largest minority in Bangladesh, according to the 2022 census. Because of persecution by sections of the majority community, especially in the countryside and migration to India, the percentage of Hindu population is down from more than 22 per cent in the 1940s to less than 8 per cent now. Braving all kinds of attack and harassment, including filing of cases of anti-national activities against minority community leaders, Hindus, Christians and Buddhists have started holding impressive demonstrations in the country’s major cities protesting against their unchecked victimisation.

In the meantime, Indian-American Congressman Raja Krishnamoorthy has urged the US State Department to do the needful for protection of Hindus and other minority communities in Bangladesh. Yunus, as also the army in Bangladesh, will do well to remember that for the country to take a leap to developing country status, it will need financial and technology support of developed countries and unhindered access to their markets. The image of the country will be sullied and foreigners will be wary of dealing with Bangladeshis if the Islamist forces are allowed to run a jihad against the minority communities.

For more details visit us: https://lokmarg.com/