Politics,

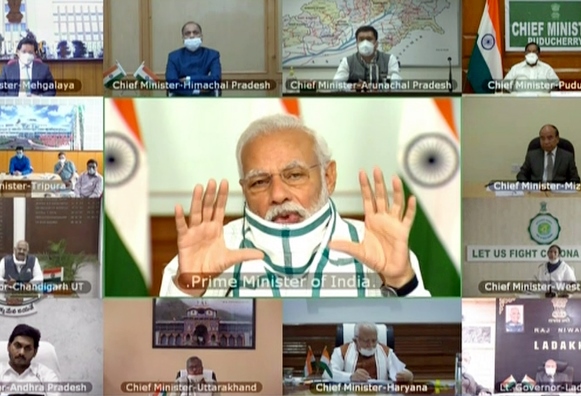

it seems, is one part of national life that does not go into lockdown. Beneath

the appearance of the whole country united in dealing with the Covid-19

pandemic, the undercurrents of State-Centre relations continue.

These

are testing times for Prime Minister Narendra Modi who hopes to come out of

this with national as well as international compliments on his handling of the

crises.

But

it is the chief ministers who are actually doing all the heavy lifting in

tackling the Covid-19 pandemic in their respective states. And they are

not all getting the equal recognitions or complete support they deserve.

Faced

with a serious public health emergency and a looming economic crisis, the chief

ministers have a lot at stake and are, therefore, putting their best foot

forward in managing the deadly coronavirus outbreak. They know they will be

judged by their handling of the crises.

Kerala

chief minister Pinarayi Vijayan and Rajasthan’s Ashok Gehlot have come in for

praise for their quick and deft management of the pandemic. Kerala was a step

ahead of other states as a proactive chief minister lost no time in announcing

a slew of social welfare measures and initiated steps for setting up quarantine

centres and testing facilities. Kerala has an advantage over other states as

successive governments have invested heavily in health infrastructure. Gehlot

also displayed similar alacrity in ordering an immediate shutdown, door-to-door

surveys, testing and monitoring in Bhilwara when it was hit by a rush of

infections. The Bhilwara

model has since been replicated in other states.

Among

the other chief ministers – Bihar’s Nitish Kumar and West Bengal’s Mamata

Banerjee – face a big challenge as Assembly elections are due in both the

states. Bihar goes to polls later this year while elections in West Bengal are

due next year.

Of

the two, Nitish Kumar has to be on top of his game because the Bihar Assembly

elections are to be held this November which gives him a small window of opportunity

to contain the pandemic. The chief minister’s handling of the corona crisis

will predictably be a major issue in these polls and have a huge bearing on

Nitish Kumar’s electoral prospects. Though his government is making all-out

efforts to procure testing kits and protective equipment for the medical staff,

the chief minister has a tough task on hand as Bihar does not boast of a strong

health infrastructure.

Then

there is the troubling issue of migrant workers from Bihar who have been

working in other states but now wish to return home as they have no jobs or

money. Nitish Kumar was initially reluctant to facilitate their return as there

was a fear that the infection could spread to the rural areas with the influx

of such a large population. He first transferred a sum of Rs. 1,000 each to the

one lakh-plus stranded migrant workers but later agreed to ferry them back

after the Centre made necessary arrangements for their journey home by train.

Nitish Kumar was forced to give in because migrant workers are an important

vote bank as most of them invariably come home to cast their vote.

As

BJP’s alliance partner, Nitish Kumar has been fortunate to get special

treatment from the Centre which is more than willing to bail him out. The

saffron party also has a big stake in the coming assembly election in Bihar.

Nitish Kumar is further lucky as the opposition in Bihar is leaderless and

hopelessly divided.

Mamata

Banerjee, on the other hand, has a match on her hand as she has to contend with

a strong and powerful rival in the BJP. There is simmering tension

between the Modi government and Mamata Banerjee with the Centre accusing her of

withholding accurate figures of the corona cases and for not providing adequate

quarantine centres and further lagging behind in testing. She has also received

a lot of flak for indulging in minority appeasement by not enforcing the

lockdown too strictly in the minority-dominated areas during Ramzan. To make

matters worse, West Bengal governor Jagdeep Dhankar has shot off a series of

letters to Banerjee charging that she had committed “monumental blunders” in

handling the pandemic.

Desperate

and working hard to expand its footprint in West Bengal, the Centre has been

particularly critical of the Trinamool Congress chief as the BJP believes this

is an opportunity to show Mamata Banerjee in poor light.

Although

West Bengal had ordered a lockdown before the Centre’s announcement and took

necessary measures to manage Covid-19 cases, the Modi government chose to send

an inter-ministerial team to the state for an on-the-ground assessment of the

situation. This led to a war of words between the BJP and the Trinamool

Congress with Mamata Banerjee accusing New Delhi of playing politics by singling

out West Bengal for this treatment. Banerjee further alleged that the Centre

had deprived West Bengal of its share of taxes and ignored her requests for

additional funds required by the state to manage the pandemic.

While

the Centre has not missed this opportunity to discredit Mamata Banerjee, it has

been more generous towards BJP chief ministers. Madhya Pradesh’s Shivraj Singh

Chouhan, Gujarat’s Vijay Rupani and Uttar Pradesh’s Yogi Adityanath are

struggling to contain the rising number of infections in their state but not

too many questions are being asked of them by New Delhi.

Chouhan

has a convenient explanation that he did not have sufficient time to make the

necessary arrangements to deal with a crisis of this magnitude since he had

taken over as chief minister when the pandemic had already gained a foothold in

the state. However, Chouhan has no explanation for the fact that he had failed

to appoint a health minister for nearly a month after he was appointed CM.

Unlike

Chouhan, Vijay Rupani ought to have done far better as he inherited the famed

Gujarat model of development, put in place by Narendra Modi when he was chief

minister. This was expected to serve him well in the current situation. As it

happens, the rate of infections in Gujarat is high and is continuing to climb.

Rupani’s

lacklustre performance in managing the pandemic is matched by his poor handling

of the large number of the restless migrant workers who were housed in

makeshift camps in Surat and Vadodara. There have been several instances of

violent clashes between the police and the migrants who wanted to go back home,

giving the distinct impression that no one was in charge.

Similarly,

Yogi Adityanath’s efforts in dealing with the pandemic have also been found

wanting. He is not helped by the fact that Uttar Pradesh’s health care

infrastructure is shoddy to say the least. But, in his trademark style, Yogi

Adityanath has conveniently added a communal tinge to Covid-19 pandemic and

blamed the minorities for spreading the virus after a number of infections were

traced to the Tablighi Jamaat assembly in Delhi. This has been exploited as a

timely distraction from his government’s incompetence.

Though

Modi is being heaped with praise for his decisive leadership in this hour of

crisis, the fact is that it is the chief ministers who have led from the front

in this battle. There have been some signs of tension between the Centre and

the states over the lack of funds and centralisation of powers by New Delhi

but, for a change, the Modi government has chosen to listen to the chief

ministers. It agreed to lift the ban on the sale of alcohol, as demanded by the

chief ministers, as it had deprived the state governments of a huge

source of revenue which, it was pointed out, could have been used to ramp up

their health infrastructure.

It

is now to be seen if the Centre will put aside politics, be a uniting force, go

a step further and release the pending share of taxes to the states and provide

them with the monetary assistance they have demanded to help them deal with the

corona crisis, whether they are pro or anti BJP.

State-Centre

politics has not gone into lockdown, but it will be wise for Modi’s BJP to

suspend it at least until the nation gets through the crises.