On 9th December 2022, Kirodi Lal Meena, a Rajya Sabha M.P. of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) introduced a private member bill on India’s Uniform Civil Code (UCC) in the Rajya Sabha that fuelled a fresh debate on an issue, which saw no resolution even in pre-Independence India and continues to haunt the political climate of India even today.

The sensitive nature of the issue besides giving political mileage to the BJP, affects various political parties, with respect to their stand on the issue. Plus, it also puts various religious communities coming under the purview of the UCC to give up their respective Personal Laws, particularly the Muslims, which are the largest religious minority in the country.

Let’s dissect the political motives first and then the response of the affected communities.

First, the audacious move of tabling the Private Member Bill in the Rajya Sabha came just one day after the BJP secured victory in the Gujarat assembly polls in December last. It reinforced the BJP’s political manifesto of enforcing Hindutva, which may also serve as the lynchpin of its political strategy for the upcoming general elections in 2024, by polarising the public.

Further, the second move to seek public opinion on the proposed UCC, in absence of any Draft of the proposed Bill, was a very astute move by the BJP. As it came within a week of the opposition parties’ meeting in Patna in June to formulate a united front and strategy to counter the BJP in the upcoming 2024 elections. As expected the move sowed division within the opposition’s ranks. Further, it saw an immediate half-baked response from the so-called leaders of the religious minorities – particularly the Muslims.

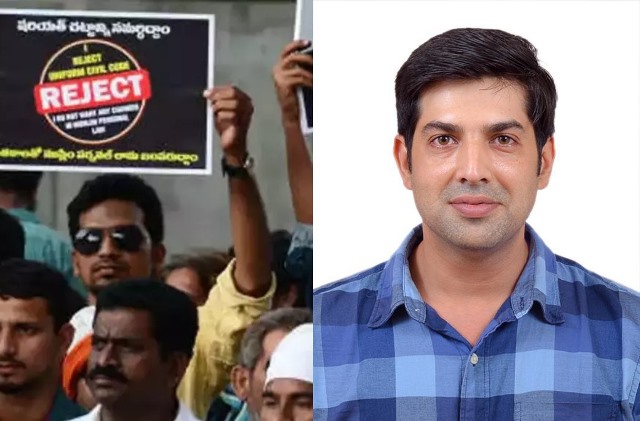

Muslim religious and community leaders without batting an eyelid immediately started opposing the UCC, and didn’t stopped to dwell on what grounds they were protesting and we saw a plethora of sentimentally rich and logically poor responses coming forth from them. The only common stand they took was that they oppose any interference in the Muslim Personal Law.

But I’m sure, neither the leaders nor their supporters know which Muslim Personal Law they are talking about. The one codified by any Muslim rulers like the Mughals, the Khiljis or the Tughlaqs or the ones before them? The answer is NO. In fact, the British colonialists codified the prevailing Muslim Personal Law, without any consultations from any Islamic jurist or scholar.

Before 1937, Muslims of all denominations, all over India, followed the uncodified local Hindu customs, practices and usages in addition to their personal law as per the Sharia. So the British just concurred on codifying the prevalent practices relevant to the marriage, divorce etc., but changed the ones relating to succession and division of property, in the case of Muslims.

It would be interesting to know at whose behest the colonial rulers codified the Muslim Law of Succession and Inheritance. It was none other than MA Jinnah, the leader of the Muslim League.

The Shariat Act of 1937 was imposed on Indian Muslims as a win-win political deal between the British, keen to divide Hindus and Muslims, and the Muslim League, keen to lure the Muslims away the Congress. In a manner this also suited Jinnah’s political strategy on how to secure a separate country for the Muslims, but it had an added personal angle also to it.

MA Jinnah’s daughter Dina married Nevile Wadia – a Parsi, against his wishes, though he himself had married a Parsi lady, Rattanbai Petit. To disown Dina and leave no inheritance for her, Jinnah made use of the recently introduced Shariat Act 1937 and nominated his sister Fatima as his successor. The Act, a joint strategy of the British and the League, contained provisions to sabotage the Islamic Sharia, by secretly smuggling the Hindu customs and usages into the 1937 Act to save the property rights of the Muslim leaders, Jinnah and the zamindars from harm by the Islamic Sharia. Did the Shariat Act of 1937 — now acclaimed as the holy law of Islam — contain Hindu law provisions to secure the property rights of the League leaders? Yes, it does.

Historian, KK Abdul Rahiman in The History of the Evolution of Muslim Personal Law in (1986) says the British gave strength to customs and usage that had long been adhered to particularly in matters of succession by sections of Indian Muslims.

Further, we have to realise that the UCC would not only affect Muslims but also Hindus, Sikhs, Christians, Jains, Jews, Parsis and other minorities and scheduled tribes in the country. And at the moment it is just a political gimmick of the government to polarise the electorate and also sow seeds of discord amongst the unified opposition. Muslim leaders need to bring other communities leaders at the same platform and also inform their Hindu brethren that the UCC will abolish the HUF provisions for filing Income Tax, thus it would increase the tax liability of Hindus also.

The UCC Bill has been introduced as a political reform by the BJP, guided by principles of Hindutva, as a response to replace the existing complicated set of personal laws. These personal laws are so complicated that even the Britishers didn’t dare to interfere with them. Further, the Constituent Assembly, besieged by two schools of thought, one supporting the UCC argued that it provided for the emergence of a secular and progressive nation, while the opponents felt it to be conflicting with the ideas of inclusiveness and pluralism, deemed it fit to circumvent the issue and leave it at the moment and thus chose to include it under the Directive Principles of the constitution, under Article 44 of the Constitution, and leaving it for the future generations to sort it out.

A realistic and practical understanding of how personal laws operate will indicate that the state’s organs and the Indian society are yet not ready, even after 73 years for the substantial revamp that such legislation would bring. Instead of gunning for political gains we should try to reflect the rich Indian diversity of traditions and their importance in common Indians’ daily life.

Lastly, the manner in which the Muslim leadership responded to the government’s move, shows its complete immaturity and the set manner of its traditional, out of touch with reality reactive response, completely bereft of any political nuances and strategy, which was also evident during the Babri Masjid movement, Triple Talaq issue etc.

Though it is high time but still there is time for the Muslim leaders to formulate a Unified Strategy and response to the UCC, in consultation with leaders of other religious minorities and political parties, so that this time they don’t get defeated by the government in its anti-Muslim campaign, though the chances of any such endeavour seem very remote.

(Asad Mirza is a Delhi-based senior political and international affairs commentator)