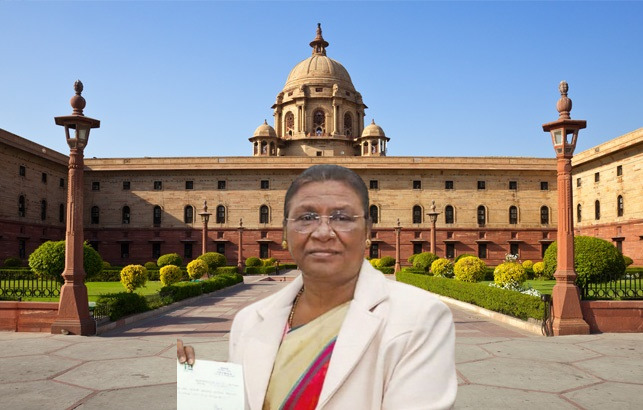

In electing Droupadi Murmu, a tribal woman, as the President, a college of India’s lawmakers will be maintaining a record far better than Britain, the United States and others who swear by democracy, gender equality and diversity, and vigorously prescribe it for other societies.

In the unlikely event of her losing, she will, at least, not be called a ‘b…ch’ the way Hillary Clinton was, before and after being defeated. Sadly though, calling names and targeting women and the weaker sections of the society is on the rise in India as well.

No need to bother that it is called Rashtrapati Bhavan, denoting a male occupant. Murmu will be the second woman to enter it after Pratibha Patil ended her tenure a decade back. What was derided as tokenism then will become the norm. But whether that helps women and tribal remains to be seen.

Talking of norms, India’s past record has been one of religious diversity with two Muslims and a Sikh. Although chosen by the prime minister of the day – which makes Indian democracy, essentially a “prime minister-o-cracy” – past presidents have not necessarily been politicians and not always belonged to his/her party.

Look at their eminence. The first, Rajendra Prasad, a front-line freedom fighter, chaired the Constituent Assembly. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan was a philosopher whom even Joseph Stalin heard with respect. Zakir Husain set up educational institutions. Scientist APJ Abdul Kalam, a devout Muslim who also visited Hindu temples, remained a national favourite, enough to be considered for a second run, long after demitting office.

Giani Zail Singh, although not a part of the social elite, defied a mixed assessment of him before, during and after his tenure as the president. He bore the pain of witnessing his faith’s most revered shrine being stormed.

Few would remember that Murmu was also in the reckoning in 2017. In selecting her, Prime Minister Narendra Modi-led ruling alliance made a deft political move, wooing an undecided Odisha, where Murmu was once a minister, and Jharkhand that has 27 percent tribal population. The opposition-ruled Jharkhand was a “swing state”, to use the lexicon of the American elections. It now bridges the modest shortfall in voters’ and ensures her victory.

It wasn’t so before. Many of the 14 past presidents won after token contests. Opposition candidates resigned top positions to contest, although the outcome was foregone. That, in itself, testifies to India’s democratic tradition.

The opposition did have a chance – arithmetically, though not politically – but frittered it away. Differences – ideological, individual and ego-fed – led to some parties treated as untouchables. Opposition’s Mayawati will vote for Murmu. Unsurprisingly, two octogenarians, Farooq Abdullah and Sharad Pawar declined, and so did Gopal Krishna Gandhi.

Yet, the choice of Yashwant Sinha, an administrator with vast experience who, at 84, continues to fight, ‘relentless’ as the title of his memoirs suggests, symbolises a contest, not for votes, but of ideas and changing values that the polity is currently witnessing.

Times are a-changin. That BJP president J P Nadda introduced Murmu on the party platform and not as the NDA nominee. The other is her comparison with Radhakrishnan, as she was once a teacher.

India has come a long way, in terms of the candidate’s curriculum vitae (CV), but it has also traversed from the hallowed portals of Oxford and Cambridge universities to the classrooms of its much-neglected tribal belt.

Murmu’s choice, it is being said, falls well within the ‘Hindutva’ plans of appropriating non-Hindu, and majorly Christian, tribal population across the heartland to the North-East. Only time can tell if this goes beyond tokenism and benefits those who form eight percent of the country’s population. And how it furthers the majoritarian agenda.

Nobody has talked of a second term for the outgoing Ram Nath Kovind. For the record, no President has been repeated except the first, Rajendra Prasad. He was Jawaharlal Nehru’s political equal. Nehru’s attempt to elevate the then Vice President Radhakrishnan after Prasad’s first term was disallowed by the Congress seniors.

Indeed, the two had differences in their respective roles. Prasad consulted experts who told him that the Indian Constitution did not envisage an activist president. That has settled the issue.

This time on, there is none of that animated coffee house debate canvassing more powers to the President vis-a- vis the Prime Minister. It is a useless political exercise.

The Constitution prescribes an all-powerful Prime Minister and his/her cabinet and a President who is generally titular and ceremonial, playing a key role only in the formation of a government.

To that, one must add troubled times that befall us from time to time, when he/she is also the conscience-keeper of the nation – but one who must act only within the Constitution’s ambit.

Some, but not all, Vice-Presidents got elevated to the presidency. Among those who did not were Justice Hidayatullah, B D Jatti, Krishan Kant and Hameed Ansari. Ansari got two terms as the Vice President.

Whatever their functions and powers, the offices of the President and the Vice-President are political in essence. This necessitates that they are in tune with the thinking and actions of the elected government of the day. This does not always happen and even if the institutions do not clash, those occupying them have differed on issues time and again.

Zail Singh did convey his unhappiness at the storming of the Golden Temple and wished to visit it. His vibes with Rajiv Gandhi were iffy and a coterie in the Congress party exploited it. Those were turbulent times, but wiser counsel prevailed to prevent a political face-off that would have set a wrong precedence.

K R Narayanan was unhappy with the Gujarat riots of 2002. His wife received and consoled in the Rashtrapati Bhavan women of the victims’ families.

Pranab Mukherjee and Ansari were critical, but kept well within the ambit of public and political correctness, of the spirit and intent behind some of the omissions and commissions by the Modi government and/or the impact they caused. Both stressed on the need for rule of law to prevail at all times and on the wisdom of the government carrying all sections of the people along.

Both sought to hold the mirror to the government leadership, stressing the need for an inclusive approach in times of protests by many sections of the society over perceived acts of intolerance by members of the government, the ruling party and their numerous front organisations. All that has ended with their exit.

Ansari’s emphasis on treatment of religious minorities earned him much trolling in the social media – mainly because he is a Muslim. He also earned from Modi a farewell, loaded with sarcasm and political messaging.

Mukherjee and Ansari have told their stories in their memoirs. Whether they got paid the way the Clintons ($15 million) and the Obamas ($80 million) is a different matter. But for sure, they did not descend as Members of Parliament like Pakistan’s President Asif Ali Zardari. Nor did they launch a political party or turn on TV anchors like General (retd.) Pervez Musharraf!

Come August, there will be a vacancy for the Vice President’s office. Will Venkaiah Naidu, like Ansari, get a second term? The “prime minister-o-cracy” may have already worked that out.

The writer can be reached at mahendraved07@gmail.com