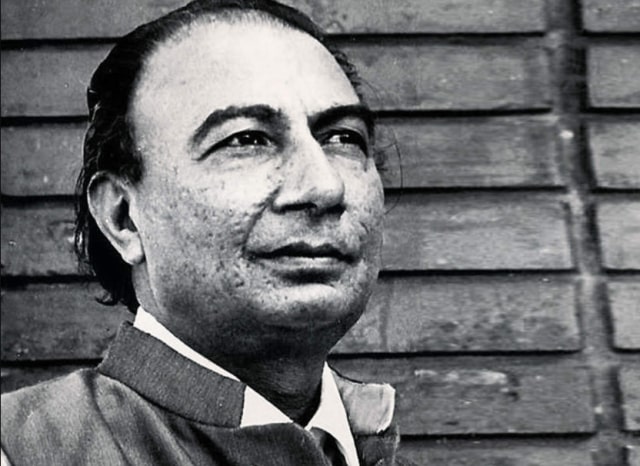

If India is

to be identified with a voice, arguably though when views can violently differ,

it would have to be that of Amitabh Bachchan.

Arguable it

was even half-a century back when first heard in a background commentary in

Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome (1970). Sen

used only his first name and paid Rs 300. Before that, All India Radio (AIR),

the only spoken mass medium then, had rejected it.

Today, the baritone,

both God-given and cultivated, resonates with an impressive filmography and an

equally respectable persona of a bespectacled gone totally grey, his tall,

lanky frame filled-out with age.

Amitabh continues

to sign more films than actors two decades younger. He endorses products that

earn him more money and visibility than films. The toast of any gathering he selectively

attends, he also promotes many a noble cause while maintaining, gingerly, his

proximity with politics and politicians who matter.

His golden

jubilee in cinema this year is not unusual, nor the number of his films, 234

(including three in making). Malayalam cinema’s superstar Prem Nazir

(1926-1989) did 720 films. Ashok Kumar had done 326 in a career spanning 61

years. Ailing occasionally but still on the roll at 76, having begun late at 27,

Amitabh is unlikely to match them in screen-longevity and film numbers. In

terms of earnings, too, he stands way below Salman Khan and Deepika Padukone, seventh

among the richest Indian celebrities assessed by Forbes Magazine last December.

He has made the term Bollywood that remains

his principal platform seem respectable when vigorously disputed by the

marquees of India’s regional cinema. While deprecating Bollywood’s craze for Hollywood,

he did a solitary Hollywood film. Baz Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby (2013) has him playing a non-Indian Jewish

character, Meyer Wolfsheim.

Many would

agree that Amitabh could have ventured into Los Angeles any time with his

cultured voice, acting talent and market pull among the vast Indian diaspora.

Not chasing Hollywood and staying rooted in Mumbai is a clever move typical of him.

Not for him bit roles playing brown man in a black-and-white milieu. And, he

needs to proudly defend his stardom.

Stardom took

a while coming although was an “officially sponsored” actor, perhaps, India’s

only one. On the threshold of half-a-century, he may not like this recall.

Renowned Hindi

poet-scholar Harivansh Rai and Teji Bachchan were close to then Prime Minister

Indira Gandhi. She was said to have addressed letters to friends K A Abbas and

Nargis. Amitqbh signed his first film, Reshma

Aur Shera after Nargis passed on the letter to actor-filmmaker husband

Sunil Dutt. Abbas asked Amitabh to get his father to telephone him before he

could consider him for Saat Hindustani.

Dutt’s film was delayed for want of funds and logistics difficulties in

Rajasthan’s desert. Ironically, he plays a dumb, minus his baritone. Abbas’

film came first and he was noticed.

Film

historian Gautam Kaul recalls that he accompanied Abbas on a talent-scouting

visit to the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII). That attracted Jaya

Bhaduri, a student who had been introduced by Satyajit Ray in Mahanagar (1965). That makes her his

senior in cinema. They paired in Zanjeer,

Amitabh’s first big hit. Married then, they remain Bollywood’s first couple.

His honing

was privileged, but far from cinema. At Sherwood, a public school, he dabbled

in English theater. At Delhi’s Kirori Mal College, he was one of the ‘players’.

A corporate job took him to Calcutta (now Kolkata) and then Bollywood happened,

not without struggle.

At a time

when India was experiencing its ‘parallel’ cinema where one risked being labeled

“non-filmy” as per prevalent Bollywood parlance, Amitabh was lucky to get

noticed by some of the top directors of the day. He achieved stardom before

Naseeruddin Shah, Shabana Azmi and Om Puri and others from that flock. He paired

with potential rival Vinod Khanna and with Rajesh Khanna, already a super-star.

He was

noticed after being paired with Rajesh in ‘Anand’

and “Namak Haram”. Although a

mannerism-driven Rajesh had the best dialogues and audience sympathy on dying

in the climax, Amitabh overshadowed him in terms of presence and performance.

Indeed, Amitabh’s rise came after Rajesh’s dizzying but meteoric rise and fall,

along with that of Navin Nischol. He paired with Vinod Khanna but the latter’s

forays out of cinema and into spiritualism put him out of the race. Amitabh was

lucky, again.

In

socialism-driven cinema of the 1970s, Amitabh emerged as the “angry young man”

with ‘Zanjeer’ and ‘Deewar’. But he also sustained

Bollywood’s raucous romance (Amar Akbar

Anthony). The dhoti-clad poet also donned suite-boot in “Kabhi Kabhi” rendering an urban touch

to Sahir Ludhianvi’s exquisite Urdu poetry. Writer-duo Salim-Javed wrote their

best lines for ‘Sholay’.

His partnering

contributed to the success of directors Prakash Mehra and Yash Chopra and in

later years, Karan Johar, R. Balki and many a fresh talent. He is associated

with some landmark films like ‘Black’(2005)

‘Pink’(2016) and ‘Pa.’(2009)

Amitabh’s

political career was brief. As one who grew along with Rajiv Gandhi, he agreed (some

say reluctantly) to contest parliamentary elections in 1984. He defeated H N

Bahuguna, a major opposition leader.

His first

day in parliament was a spectacle. Ministers and lawmakers alike thronged to

get his autographs (“oh, for my grandson,” one said sheepishly). But he made no

speech and would impassively watch the House proceedings, touching his face

involuntarily as if missing the greasepaint.

In my only

encounter with him in Parliament’s corridors, I sought his reaction to the

Annual Budget. “I have no reaction.” I scolded him, almost: “A major concession

is made for the film industry and you have nothing to say?” “I welcome it,” he

said and rushed off.

He resigned

when the Bofors gun deal scandal scalded friend Rajiv and then lamented in a

Times of India interview that “politics is a cesspool.” Truth may never be

known. He was among those who had let down Rajiv, critics say. The

Gandhi-Bachchan breach, it is believed, remains to this day.

A serious career

decline between 1988 and 1992 saw a series of flops. He looked jaded. His film

production venture skidding, he went virtually bankrupt. But he climbed his way

back into reckoning as actor, despite the advent of three young Khans – Aamir,

Salman and Shah Rukh.

Succeeding

the three post-Independence greats – Dilip Kumar, Dev Anand and Raj Kapoor and

straddling the Khan era, Amitabh has played a range of characters, from Sufi,

Shakespearean, suave romantic, a conman, a policeman, a soldier, a stricken child,

a ghost, a drunkard — all that Bollywood offers. Choosing favourites from among them is well-nigh

impossible. He has starred opposite son Abhishek and daughter-in-law Aishwarya

and outsmarted both – of course, the director and the script demand that.

A detailed

narration of his career would take more space than permitted here. Roles are

written for him. Whatever be the performance of others in the ventures, he does

not let you down. And that is remarkable in 50th year.

His

anchoring “Kaun Banega Karorpati,”

the Indian version of “Who Wants To Be Millionaire”, remains a landmark in

Indian television. Beginning 2000, it has had nine seasons and demand for it

seems unending among advertisers and family audiences. In a way it also marks

the evolution and ageing of Amitabh.

To be seen

with him by the millions, is a lifetime’s achievement for the young and old,

grannies and housewives. They acknowledge this gratefully, some tearfully. They

narrate to him their hopes. He inculcates in them aspirations and family

values. Money-earning, although a huge

motivation, becomes incidental when they are before him.

If his

success is to be measured in terms of awards and accolades, he has numerous, including

four National Film Awards as Best Actor, many at international film festivals. He

has won fifteen Filmfare Awards and with 41 nominations overall, is their most-nominated

performer.

In 1991, he

became the first to receive the Filmfare Lifetime Achievement Award established

in the name of Raj Kapoor. The magazine crowned him as Superstar of the

Millennium in 2000.

In 1999, he

was voted the “greatest star of stage or screen” in a BBC Your

Millennium online poll. The organisation noted that “Many people in the

western world will not have heard of [him] … [but it] is a reflection of the

huge popularity of Indian films.”

He has been

conferred two honorary doctorates by the universities of Madras and Manchester.

He can use Dr. as prefix, but does not.

Conferred Padma Shri (1984), Padma Bhushan (2001) and Padma Vibhushan (2015), now, Bharat Ratna, India’s highest civilian national award, awaits him.

The writer can be reached at mahendraved07@gmail.com