Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi hailed the “steady progress” made in improving the bilateral relationship, after his meeting with the Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi. On its part, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs said that the two countries have entered a “steady development track” and they “trust and support” each other.

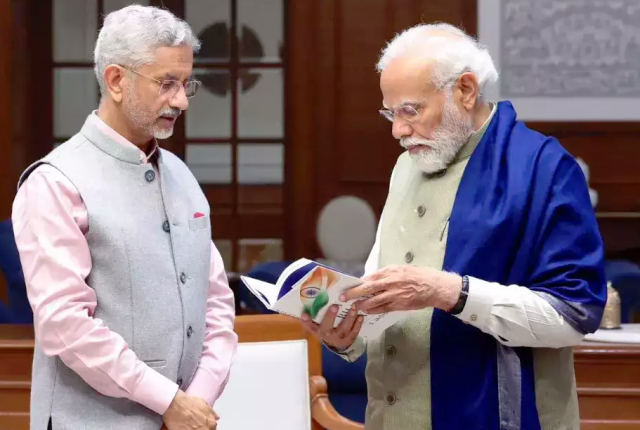

Wang also met with Foreign Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar as well as National Security Adviser Ajit Doval to discuss the countries’ disputed border. India’s Ministry of External Affairs said Wang’s meeting with Doval discussed “de-escalation, delimitation and boundary affairs.”

However, what was more important for the Indian diplomats was the increasing bonhomie between Islamabad and Dhaka after the fall of former Prime Minister Sheikh Haseena, who was ousted after a deadly civil unrest.

The Indian defence and security establishment, watches the increasing closeness between the two countries with serious concern. Added to this is are widespread apprehensions found in the Indian defence circles, related to the cornering of the country, as China, Pakistan and Bangladesh forge closer ties.

New Delhi’s concerns are particularly related to the Siliguri corridor, known as India’s chicken neck. The growing Chinese and Pakistani influence in Bangladesh has also put an additional burden on the Indian defence forces, which are now stretched across the entire border, LoC and LAC. Reportedly, Pakistan’s top spy officials have made frequent visits to Bangladesh in a bid to contain India’s growing influence in the region.

During Pakistan’s Commerce Minister Jam Kamal Khan’s visit to Dhaka last week, the Bangladesh government expressed its keenness to reduce the trade gap with Pakistan through a series of measures, including the formation of a trade and investment commission, withdrawal of anti-dumping duties on hydrogen peroxide exports, and reinstatement of duty-free export quotas for tea.

“We had a very intensive discussion. We are working on reactivating the Bangladesh-Pakistan Joint Economic Commission (JEC), which has been inactive for more than a decade- and-a-half, and also forming a new trade and investment commission to enhance bilateral trade and investment cooperation,” Bangladesh’s Commerce Adviser SK Bashir Uddin said.

Bangladesh also sought Pakistan’s support to develop the country’s leather and sugar industries, he said. Bashir said Bangladesh once enjoyed a duty-free quota of 10 million kg of tea exports to Pakistan and requested the reinstatement of that during the meeting.

About food trade, he said, “We import food from many countries. Wheat is our main import from Pakistan. If we get competitive prices, we will welcome more imports.”

Responding to a question on whether Bangladesh is leaning towards Pakistan, the adviser said, “We are leaning towards everyone – Pakistan, the United States, and even India, from where we are importing onions. Bangladesh’s interest comes first.”

Meanwhile, Pakistan’s Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Muhammad Ishaq Dar also travelled to Dhaka over the last weekend, marking the first such high-level trip in 13 years.

Dar’s two-day official visit, was described by Pakistan’s Foreign Ministry as an “important step in strengthening bilateral ties,” which also included meetings with leaders of several political parties, including the BNP and Jamaat-e-Islami, with the latter having historically opposed Bangladesh’s independence in 1971, making the engagement especially noteworthy.

According to The Daily Star, both countries plan to revive their Joint Economic Commission, with a meeting expected in September or October, the first in nearly 20 years. Pakistan’s Finance Minister Muhammad Aurangzeb is scheduled to visit Dhaka for this purpose.

A visa-free pact was formalised following delegation-level talks between Dar and Bangladesh’s Foreign Affairs Adviser Mohammad Touhid Hussain. Other agreements aim to bolster cooperation in trade, diplomatic training, education, media, strategic studies, and cultural exchange.

At a joint press conference, Dar stated that Pakistan seeks “a new era of partnership with Bangladesh” and called on the government, political parties, and youth to unite in strengthening bilateral relations.

Adding further to this spate of visits other noteworthy visits between Bangladesh, Pakistan and China, Bangladesh’s Chief of Army Staff, General Waker-Uz Zaman, travelled to China for an official visit where he met senior civilian and military leaders.

His trip underscores Dhaka’s growing defence ties with Beijing, which has long been a strategic partner for Bangladesh in military training and procurement.

Meanwhile in Islamabad, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi met with Pakistan’s Chief of Army Staff (COAS), Field Marshal Asim Munir, at the General Headquarters (GHQ).

The discussions apparently centred on South Asia’s fragile security environment, with a special emphasis on Afghanistan, India, and the Gulf area.

The discussions, according to reports, centred on deepening economic and security partnerships, with emphasis on the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and regional stability.

Amidst all this plethora of visits, comes the news that Pakistan’s Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif will soon travel to China. His visit will mark the launch of the second phase of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor – CPEC-II, which has been delayed for years. Pakistan now presents it as a grand plan for jobs, industry, and growth. At its core, it deepens China’s grip on Pakistan’s economy.

For India, the CPEC-II is more than an economic project. It runs through Gilgit-Baltistan and part of Pakistan-occupied Kashmir. India claims these territories. By expanding activity there, China and Pakistan reinforce Pakistan’s control. This challenges India’s sovereignty.

Gwadar adds to the concern. The port is not only commercial. India fears it may host Chinese naval assets. With the CPEC-II, port expansion makes that risk sharper. Industrial hubs add another layer. China’s projects often blur civilian and military use. SEZs may double as logistics and surveillance sites against India.

The launch also comes at a delicate time. India and China are talking after years of border standoff. Still, Beijing tightens its embrace of Islamabad. This signals a double move. In all this, India sees a deeper “string of pearls” taking shape. From Hambantota in Sri Lanka to Kyaukpyu in Myanmar, Chinese-backed ports now ring India’s maritime zone.

For Pakistan, the gamble is already high. Its debt to China from CPEC-I already weighs heavily on its economy. The CPEC-II will add more.

Past promises also loom large. The CPEC-I was hailed as a “game-changer”. Instead, Pakistan ended up with rising debt, energy shortages and delayed projects. Many now fear that the CPEC-II may repeat that cycle.

Taken together, these parallel diplomatic, military, and economic engagements point to a recalibration of regional ties, with both Beijing and Islamabad seeking closer coordination with Dhaka while also reinforcing their bilateral partnership. These developments will put the Indian diplomats under pressure to pursue a course of action, which counters these three countries and as India has never indulged in such hypocritical or playing one country against another to ensure its interest, it may seem a little tough.

(Asad Mirza is a New Delhi-based senior commentator on national, international, defence and strategic affairs, an interfaith practitioner, and a media consultant.)