Elections have determined Bangladesh’s course even before its birth, which was triggered by the way they were held in 1970 in Pakistan. Compounding an intense internal turmoil, the ones due on February 12 are for the first time being held with a foreign military presence on its soil, along a troubled border with Myanmar, where a pro-Beijing military junta has lost control to rebel groups. A global power play of the United States-led efforts to confront China is underway.

In a repeat, history has judged Bangladesh’s founding leader, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, and now, his daughter. India’s former envoy to Dhaka, Pinak Ranjan Chakravarty, reminds: “Sheikh Hasina had annoyed both the US and Pakistan. She refused to submit to American demands for facilitating a military base on St Martin’s Island and the so-called “Humanitarian Corridor”, to pump in arms into Myanmar to help rebels fighting the ruling Military Junta.”

A December 2025 news clip, gone viral, has US President Donald Trump declaring, “We have decided that elections in Bangladesh would be free and fair”, and that “no extremist elements” will win. However, America’s need to confront China in a country that straddles South and Southeast Asia cannot be overlooked.

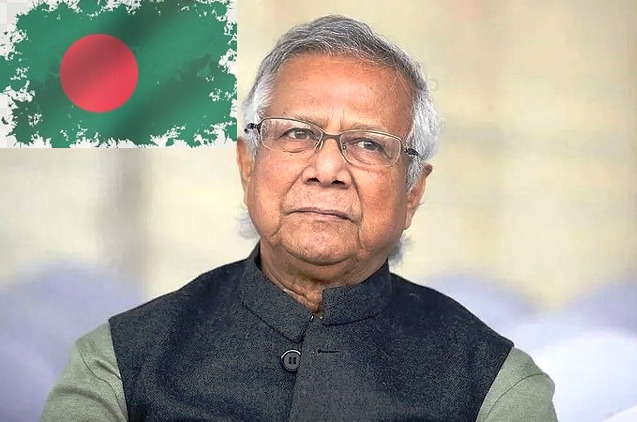

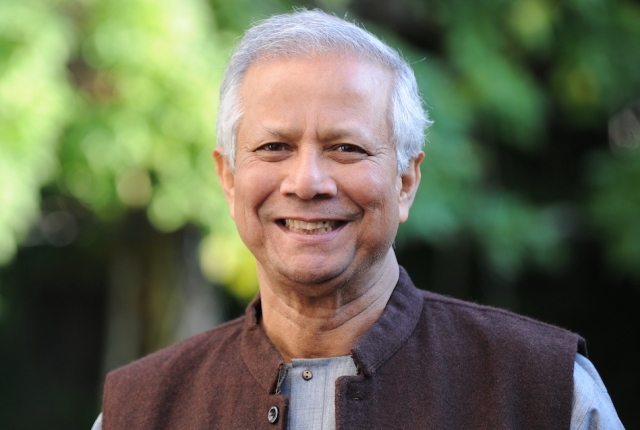

Assiduously cultivated by the Mohammed Yunus-led regime, Pakistan has returned to its erstwhile eastern province, aiding the resurgence of the Islamist forces. That questions the raison d’etre of separation. The frequent visits by Pakistani military and ISI officials have strengthened military ties and joint defence outreach with China, the biggest beneficiary of the 2024 change. And since anything happening in Bangladesh spills over to its eastern region, India sees red.

In the ensuing elections, leading an 11-party alliance, the Jamaat-e-Islami Bangladesh has disciplined cadres and wide support among the conservative Muslims in the countryside. It is in a tight race for power with the largely city-based Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) of the Zia family, which lacks such a base. According to a survey by the US-based International Republican Institute, Jamaat is the “most liked” party.

The Islamist alliance includes the National Citizens Party (NCP), of student leaders whose protests led to the toppling of the Hasina regime in August 2024. Some of its women leaders, fearing a clampdown from fundamentalist elements, chose to quit. Bangladesh has one of the largest women’s workforces in the Muslim world.

Struggling to retain identity among the entrenched Islamists, the NCP’s student leaders have forced a referendum along with the election. But the elections could minimise, if not eliminate, their future role.

The entire right-wing phalanx is anti-India. Among many things, the larger neighbour hosting Hasina has been a talking point, even with the BNP.

Hasina’s first audio conference on January 23, beyond lambasting Yunus, should have included a pre-poll, manifesto-like declaration to “stay in the race”, albeit notionally. An opportunity was missed.

Unable/unwilling to control crowds, a recalcitrant Yunus regime has sullied the diplomatic pitch. For the first time, India’s visa offices have been attacked, forcing Delhi to suspend these facilities and withdraw families of its staff for safety reasons.

The BNP is galvanised by the return from exile of Tarique Zia, just before Khaleda Zia, his mother and two-term prime minister, died. The family of slain former president General Ziaur Rahman enjoys respect and semi-official support. Tarique, the new ‘dynast’ (replacing Sheikh Mujib and Hasina), is the top favourite. After his Western ‘approval’, Yunus met him during the London exile and facilitated his return.

The stage is set for Tarique as the prime minister, it is speculated, with Yunus as the likely future president. Or, a graceful retirement for the Nobel laureate after having ‘delivered’ to his mentors.

One big hurdle is the Islamists. Yunus’ perceived proximity to the student leaders, now in his administration and in the NCP, could deny Tarique a parliamentary majority, forcing him to form a coalition government. But the BNP’s founder, Ziaur Rahman, was a soldier/freedom fighter. Despite its ‘nationalist’ ethos, during 2001-2006, Khaleda had shared power with the Jamaat. Post-polls exigencies and external pressures may dictate a repeat.

Nor can one ignore the general approval of the Yunus regime by the Western governments and the media, which has overlooked the exclusion of the Awami League, Bangladesh’s largest political party. Yunus told the BBC that the AL was “still there”, his government had no role in its exclusion, and the Election Commission had ordered it. He wasn’t asked who appointed that poll body, or, for that matter, the judges of the Crimes Tribunal who have delivered the death sentence against Hasina.

Besides having played a role in Bangladesh’s liberation, India supported Hasina, even her many autocratic ways at home, because she met Delhi’s security concerns by curbing militancy and closing down terror camps run by Pakistan’s ISI. Fostering revenge as the motive, the Yunus regime has allowed Awami League leaders and workers to be hunted down and killed, and their properties destroyed. But that is how the “winner-takes-all” politics, of the Awami League, as well, has worked in Bangladesh.

Sheltering Hasina, because Britain did not issue her a visa, hugely adds to India’s dilemma. It has exercised strategic restraint and kept up a difficult relationship, although attacks on minorities, Hindus and Buddhists have a direct bearing on India’s domestic scene.

While rights groups have documented numerous such attacks, Yunus claims that only 645 “incidents” occurred in 2025, and that just 71 of them were communal in nature. He has termed allegations of atrocities on the minorities as ‘propaganda’, pointing the finger at India. But the Dhaka Tribune newspaper (January 20, 2026) has, in an editorial, said that such attacks “are a deeply troubling reminder of a persistent and corrosive mentality that insists on retaliation over reason, and instant judgment over justice.”

Yunus had earlier argued that most attacks on minorities were “political.” He now insists they are primarily criminal rather than communal. This shifting terminology is not incidental; it reflects a deliberate effort to strip the violence of its definite religious character and obscure the identity of the victims. In reality, the choice of targets is driven by religious vulnerability.

Islamist groups have grown more visible and assertive, as evidenced by the destruction of shrines and statues and the torching of minority homes. The pattern is unmistakable. The Army Chief, Gen Waqer-uz-Zaman, citing huge quantities of arms in illegal hands, including the Islamist cadres, has cited it as one of the obstacles to a fair election.

India’s dilemma is that it feels the need to speak up for Bangladesh’s minorities because of the spill-over effect. At the same time, this hurts these minorities who are feeling persecuted and sour Delhi-Dhaka relations.

Consequently, India, while remaining diplomatic, has done little to stop the anti-Dhaka stance in its media and has allowed issues like a cricket tournament to become part of the acrimony. When Bangladesh projects a Hindu as its cricket team captain, how should India react? This symbolises the delicate Delhi-Dhaka relationship, different from other neighbours.

The international community is likely to put its stamp of approval on the election’s outcome. Its impact on Bangladesh’s constant search for national identity, however, is unclear.