Indo-Chinese border tensions rise… again!

More than a year after their last skirmish, last week Indian and Chinese forces clashed again along the Line of Actual Control (LAC), the 3,440 km-long disputed border that is not clearly demarcated between India and China in the Himalayas. The government officially informed Parliament that Chinese soldiers had tried to intrude into Indian territory in Arunachal Pradesh’s Tawang sector but were successfully thwarted by Indian forces, which were well-prepared for the attack.

There was an element of chest-beating hyper patriotism in Indian media reports about the incident. One news agency’s choice of words in its report on the clash when it said that the Indian troops deployed in the area of face-off in Tawang sector “gave a befitting response to the Chinese troops and the number of Chinese soldiers injured in the clash is more than the Indian soldiers”. In contrast, the official Chinese response was more muted. China’s Foreign Ministry gave no details of the scuffle in Tawang but said the situation on the border with India was generally stable. Beijing also called on New Delhi to implement the consensus reached between the two countries and adhere to the spirit of the various agreements and accords signed by both sides to maintain peace and harmony.

That will be easier said than done. The two sides have been attempting to de-escalate tensions along the border since 2020 when in a bigger clash, at least two dozen troops were killed. There is a bit of fuzziness about the facts surrounding the latest skirmish. New Delhi said last week that the most recent clash was in Tawang but China claimed it was in the Dongzhang area and that contrary to the official Indian view, it was Indian troops that had illegally tried to enter Chinese territory.

Much of the ambiguity over the Indo-Chinese clashes is because of the nature of the LAC. It is not demarcated accurately and because of the presence of many lakes, rivers and snow-capped hills and mountains, the topography can shift because of natural causes (for example, melting glaciers or heavy snowfall). This can bring troops from either side in confrontational situations that are often not predictable.

Then there is the genesis and history of the dispute between the two countries over the region. At its core it is all about this: Beijing believes the region that forms the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh is traditionally part of China as “South Tibet”, while New Delhi disputes that and claims that it is part of India.

Besides the fuzzy nature of the LAC, both India and China have been building defence infrastructure along the border at a high pace. This itself has sometimes led to clashes. In 2020, when India built a road to access a high-altitude air base. Since then, there have been attempts at de-escalating tension along the LAC and there have been regular military-level talks. But clashes have happened periodically till a little over a year back when the two sides decided to disengage. This December’s clash broke that entente.

China and India have fought just one actual war–in 1962, when India suffered a humiliating defeat. Yet, although there has been no full-scale offensive from either side, the simmering tension along the LAC could lead to potential threats: both countries are nuclear powers; both have large mutual interests in commerce and trade; and geo-politically a crisis between the two could have ripple effects across the globe. Talking to settle disputes is probably the only way out for the two.

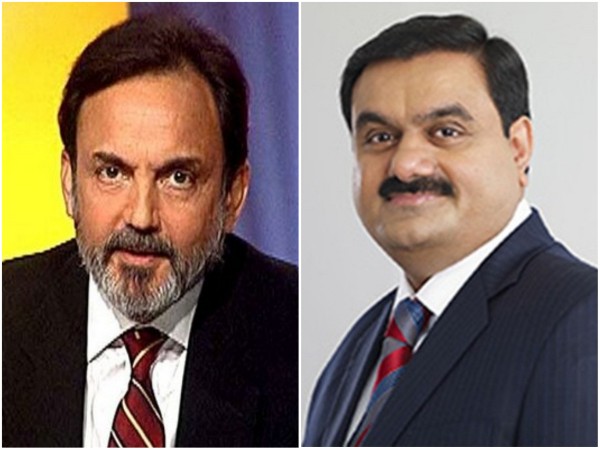

How independent will NDTV remain under its new owner?

Recently, in an interview with Financial Times, Gautam Adani, who now owns NDTV, said he had big plans for the media conglomerate. He wanted to build it into a global news brand. Adani, whose empire spans industries ranging from ports to power generation, told FT that India didn’t have a single media outlet “to compare to Financial Times or Al Jazeera”. Seemingly refreshingly, the richest man in Asia also said that he saw his purchase of NDTV as a “responsibility” and not a business opportunity.

There was a catch, though, in his references to NDTV in the FT interview. Adani’s takeover of NDTV has raised questions about the future of the news organisation. NDTV has been one of the few remaining mainstream media organisations that have demonstrated independence at the cost of riling up the establishment. Whether it has been truly unbiased and objective is open to debate but it has (unlike some of India’s largest media groups) been unafraid to be critical of authorities, including the current Modi regime. Adani told FT: “Independence means if the government has done something wrong, you say it’s wrong. But at the same time, you should have courage when the government is doing the right thing every day. You have to also say that.”

Aren’t governments supposed to be doing the right thing every day? So does a media outlet have to say so every time the government does the right thing, which is,by the way, its duty towards the citizens it governs?

I don’t know about you but this thing about cheering every time the government does the right thing, which is what its job is, doesn’t appear to bode well for NDTv’s future. But then, I may be a bit of a cynic. Dear reader, I do hope that you are too!

Has the West stolen Yoga and made it worse?

In any large western city, the sight of people rushing about with rolled yoga mats slung on their shoulders is more common than it is, say, in India. In India, where yoga originated some 5,000 years ago, it has millions of practitioners but it does not have the commercialisation and the resultant commodification that marks its expansion in the West. And now, there is a backlash to all of that.

Yoga practitioners and teachers are accusing the west of appropriating an integral part of the Indian practice of well-being by wiping out the tradition and history of yoga and replacing it with an alien western model that includes branding, marketing and massive commercialisation. According to some estimates, in 2019, the global yoga industry was worth an estimated US$37.46 billion, and it’s expected to balloon to US$66.23 billion by 2027.

Indian practitioners allege that in the west the practice of yoga has also been “whitewashed” with hardly any Indian instructors and an ethos that is predominantly ethnically white. More specifically, Indian practitioners and yoga gurus allege that yoga has become yet another workout regimen and has been stripped of its cultural and historical narrative. Others have called it the “colonisation” of yoga–something that has become inaccessible to people of colour and ethnically diverse groups.

While part of these allegations might be valid–branded yoga pants and other accessories can cost a lot and membership to yoga clubs in the west is not cheap–could the outrage against yoga’s commercialisation also be a ‘sour grapes syndrome’? After all, what stops Indian entrepreneurs and yoga practitioners from using modern marketing tools to spread the ancient practice themselves? And, if they think they are the custodians of yoga’s history and traditional values, they could even blend their marketing strategy with those so-called authenticities. Instead of looking at the West’s massive adoption of yoga as an appropriation, we should look at it as a missed opportunity.

Prohibition doesn’t work and that’s a fact

Last week, more than 60 people died in a Bihar district because they drank illegally distilled alcohol. This is not the first time that illegally distilled liquor has killed people in Bihar. Since 2016 when Bihar imposed prohibition in the state, the number of people dying or being seriously ill because of consumption of illegal liquor has been rising steadily. Hundreds have died in the state since the Nitish Kumar-led government imposed a ban on liquor.

Historically, prohibition has always been a difficult policy to implement. When the US had prohibition in the 1920s, it is believed that alcohol consumption actually went up and the government lost massive amounts of tax revenue because all of what was being consumed was illegal. The US had to abandon the policy in 1933.

In India, Gujarat has had prohibition since the state was formed in 1960 but an apocryphal story goes that its neighbouring state, Rajasthan, has a massively high rate of per capita sales of alcohol because much of what is sold there is smuggled into Gujarat. Other states such as Haryana, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, and Manipur have, in the past, imposed prohibition but have had to repeal the law when they found it difficult to implement.

Perhaps it is time for Bihar too to realise that prohibition does not really work.

Covid’s spread in China could be a global threat

After widespread protests led the Chinese government to ease Covid-related restrictions, the situation in China has turned for the worse. The country is now facing what experts are calling the world’s largest Covid surge during the pandemic. According to Chinese public health service officials, as many as 800 million people or nearly 60% of the population could be infected over the next few months. Some predictive models estimate that nearly half a billion people could even die because of the virus.

Given that the virus had been believed to have originally broken out in China in the city of Wuhan in December 2019, this can mean things have come full circle. But considering how the virus had then spread across the world for two years ravaging lives, livelihoods and the global economy, if the resurgence of Covid in China is real, it could be terrible news for the world. It is time for countries to review their policies and reinstate measures to restrict the spread of the virus again.