These are dire times for democracy thanks to happenings in the two Grand Old Parties (GOPs). America’s Republican Party remains captive of Donald Trump, despite the havoc with the presidency, ‘invasion’ of the White House after he lost and the outcry over his carting away state documents. And in India, the Congress is on a precipice.

Defeated in two parliamentary and 39 of the 49 elections to state legislatures, the Indian National Congress is losing mass support and senior members, mostly to the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The record of three generations of the Gandhis and the Nehrus who preceded is being omitted from history books. The current leadership is being challenged from within.

Whether they cannot quit or will not, is the crux of an internal churning and much public lampooning. It’s Catch-29: arguably, the party cannot grow with them, and it cannot survive without them.

The Congress is in desperate need to carry out a rigorous internal review and acknowledge that a root-and-branch re-organization and a grassroots revival are both imperative for its survival.

The Gandhis are a fair game, accused of greed for power. But as much as them, if not more, criticism ought to be directed, but is not, at the parry’s men and women who refuse to find among themselves an acceptable leader. This is from a party that elected, despite internal quarrels and factionalism, a new president and a working committee every two years. That culture died long ago.

Ironically, Sonia Gandhi, who never wanted her husband Rajiv and children to join politics, is the party’s longest-serving chief, for 24 years. Though not the first not born in India to head the Congress, she has virtually dictatorial powers in the organization. For a decade, she even influenced the policies of the government headed by a hand-picked prime minister.

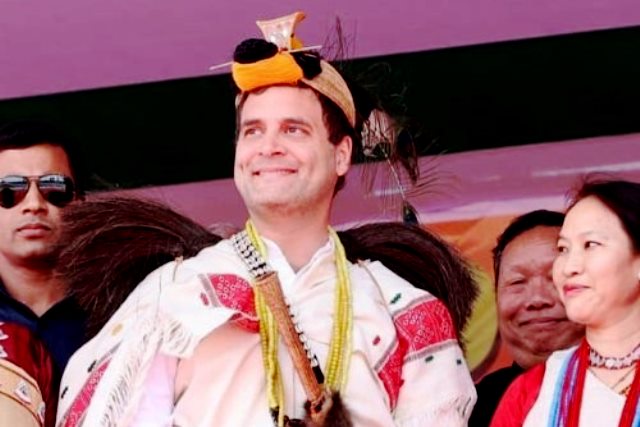

Frail and ailing, she is now called the “nominal figurehead” who has yielded authority to her children, particularly her son Rahul. He is openly called out for lacking the ‘aptitude’ required to lead the party and for “childish behaviour.” He is charged with shunning responsibility but taking all key decisions, surrounded by a ‘coterie’ of politically inexperienced aides.

Ghulam Nabi Azad, the latest stalwart to quit, is being quoted here because, with his harsh, even personal criticism, he has shown the mirror to the party. He has exposed the desperation of many more Congressmen who are afraid to speak up. If nothing else, he has nudged the leadership to announce firm dates for the much-delayed election, albeit only for the top post.

If not a Gandhi, who? Shorn of most stalwarts, having none with a pan-India image, the party is groping. An alternate plan is not in sight. The final choice may still be called, rightly or otherwise, a ‘proxy’. The seniors among the loyalists are reluctant. Truth be told, they are too used to a Gandhi to pick up the gauntlet.

Sonia’s woes do not begin or end with party affairs. The government’s revenue enforcement authorities have interrogated her several times, for several hours, on trusts and the dealings of the National Herald newspaper firm, allowing her relief only when she tested Covid-19 positive.

For once the party galvanized into action, with thousands protesting and courting arrest in many cities across the country. Leaders who have forgotten mass contact programmes were in action. The adversity augured well for the party.

But that leaves a vital question: why can’t they display the same spirit and action to protest against the government’s many actions, at the central and state levels? Many opportunities were simply wasted.

The party was squeamish about supporting protests against the citizenship laws, the farmers’ agitation, and a host of issues, including remission of the sentences of those convicted for 2002 gang-rape of Gujarat’s Bilkis Bano. Joining these and other protests, if nothing else, would have given a sense of purpose to the party cadres and allowed for mass contact.

ALSO READ: To Survive, Congress Needs A Major Split

Raising some hope amidst the gloom, beginning September 7, Rahul will ‘participate’ in the party’s Bharat Jodo Yatra covering 3,500 km from Kanyakumari to Kashmir through 12 states. Its success will depend upon the consistency with which it is conducted, the slogans raised and the message sent out, the public response it gets, the effectiveness of the follow-up done on the ground, and lastly, the media projection.

Congress’s record in recent years has been dismal on all these counts. For one, Rahul’s absence from the daily political activity is too frequent to allow for consistency. The state leaders failed to garner ground support during election campaigns.

Spirited though, Rahul’s 2019 polls campaign was no match for Narendra Modi’s relentless rhetoric. His up-front attacks on Modi’s persona, like “chowkidar chor hai” did not go well. The public shows deference, if not always respect, for office. In the media, Rahul, by his own admission, is the country’s most ridiculed person. By all accounts, he is a good person, but that is not enough in politics – not in these days of media’s weaponization and more.

In hindsight, Rahul should have launched a Yatra long ago, at the beginning of his probation in politics. He did not utilize the decade his party was in power. Suggestions that he should join the Manmohan Singh Government and gain some administrative experience were scoffed at. The family entitlement – see the Shiv Sena’s Thackerays – and top-down trajectory is difficult today.

The walkathon should keep Rahul on the move for five months. There is no clear signal if he will stick to his resolve and that no Gandhi will contest for the party chief’s post. But certainly, this may be the party’s last chance to stay relevant as a national party. Failure is a recipe for disintegration – like the last days of the Mughal Empire.

One can wish its success, not as support or sympathy for the GOP, but for the sake of democracy that needs an effective opposition and a healthy political discourse.

The writer can be reached at mahendraved07@gmail.com