Making a film with a political theme in politics-obsessed India is tricky. Few such films have been made; fewer, if not banned, have succeeded.

The uneven performance of a plethora of biopics on contemporary political figures points to this. Audiences may or may not accept a positive take, but they generally reject a negative one. This long-held trend has continued in recent years amidst selective and sustained promotion of some and bashing of some others among the nation’s political leaders.

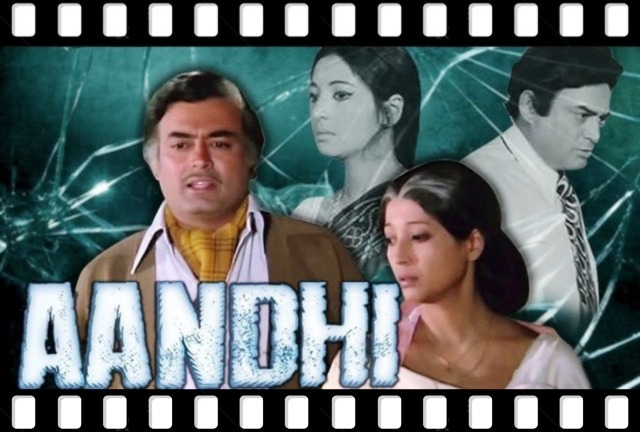

A brief comparison of two of them with identical themes. Released this year, Emergency, which recalls Indira Gandhi’s huge political misstep in 1975-77, flopped, both critically and commercially. On the other hand, Aandhi, though made 50 years ago, is remembered as a cult film.

The broad comparison is noteworthy because, unlike Emergency, Aandhi only alluded to Indira. Its makers vehemently denied that she was the target. Released during that tumultuous era, but notably before the internal emergency was imposed, the media censors banned it halfway through its successful run. This was after the film’s exhibitors had sought to cash in with posters that rhymed “Aandhi with Gandhi”. The ban was lifted when Indira lost power.

Another film, Kissa Kursi Ka, of people rising against an all-powerful Indira, was also banned and revived after she lost power. But while it sank on its second run, Aandhi ran even better when the ban was revoked.

Comparing Aandhi and Emergency offers insight into two distinct cinematic approaches to portraying Indira Gandhi—one allegorical and the other biographical.

Directed by Gulzar, Aandhi featured Suchitra Sen as Aarti Devi, a politician whose appearance and demeanour closely resembled Indira Gandhi. The mannerisms and the choice of cotton sarees were the clear giveaway. While the film was presented as a fictional narrative, some parallels to Gandhi’s life were evident. Only later, Gulzar acknowledged the movie being ‘influenced’ by Indira Gandhi’s life.

Watched by the discerning today, Aandhi is, at one level, a woman’s story, ahead of its time. It delves into the personal sacrifices and emotional complexities faced by a woman in power, highlighting the tension between public duty and private life. A triumph of the director and his writers, its nuanced storytelling and character development have lent it enduring relevance.

It humanises a powerful woman without either vilifying or glorifying her. Its restraint and dignity make it poetic rather than polemic. Few Indian films in the last five decades have elegantly combined romance, politics, and realism.

With due respect, Emergency, directed by Kangana Ranaut, who also plays the protagonist, is a direct portrayal of Indira Gandhi. The film lacks depth, and her storytelling is inconsistent. Undoubtedly a brilliant actor, however, her performance is nowhere near that of her depiction of Jayalalithaa, another formidable woman politician. She essayed that role with distinction.

ALSO READ: Biopics – Real Life Stories Retold

While Ranaut had no political axe to grind with the Tamil matriarch, incidentally an actor-turned-politician like her, Kangana’s political bias comes out against Indira. The actor-director succumbs to the current trend of what may ruefully be called “bandwagon Bollywood”. That alone makes Emergency a lesser film.

One may ask why she engages in a hagiography, depicting huge portions of Indira’s private and public life when the focus could have been the Emergency that provided enough material. In depicting the 1971 birth of Bangladesh, she wavers. The “goongi gudiya”, the dumb doll at home, transforms into a tigress in the United States, boldly telling off the likes of Nixon and Kissinger. Kangana ends up idolising her target.

One is unable to decide whether to cry or laugh at seeing Jayaprakash Narayan, Atal Bihari Vajpayee and other Indira critics singing in Parliament. This never happened, nor did Indira in real life silently nod at the then army chief, General Sam Manekshaw, asking him to “go to war”. If this is meant to be artistic liberty, it is carrying that liberty too far.

Sadly, from other production values that lure the audiences in this era of multiplexes and OTT (over the top) home theatre, Emergency has little to offer, despite many seasoned artists who come across as mere caricatures. By contrast, Aandhi scores for its music. Songs like Tere Bina Zindagi Se Koi are still iconic, speaking to universal feelings of love, longing, and missed chances. The music continues to connect with audiences across generations.

For all its political content, perceived and real, Aandhi remains a love story between Aarti and her estranged husband J.K. (played by Sanjeev Kumar). Deeply human, it is about compromise, regret, and—themes that never age. An intensely ‘private’ J.K. accepts Aarti’s public life and ambitions. The film doesn’t romanticise reconciliation but portrays it realistically, with emotional nuance.

The challenges Aarti—judgment for being assertive, strained personal relationships due to ambition—are even today very real for many women in public life.

Aandhi is strikingly relevant even 50 years after its release. It explores how public figures often sacrifice personal happiness for duty or image. That duality—public persona vs private self—is even more intense now with 24/7 media coverage, social media pressure, the expectation for perfection from leaders, particularly if they happen to be women. Forget the frequent “crashing of the glass ceiling” reports; look at the husbands behind women Sarpanches: India remains a patriarchal society, in all spheres of life.

It is a long list, and discourse could get unwieldy. Hence, a brief overview of some of the films that touched on politics before we end this. Like Aandhi, Raajneeti (2010) explores power, ambition, and political strategy. Being inspired by the Mahabharata, it is epic in scale, but lacks the emotional intimacy of Aandhi. Raajneeti is loud, complex, and masculine in its energy.

In Gulab Gang (2014), Juhi Chawla’s character, a corrupt politician, shows a powerful woman who chooses manipulation over idealism — a sharp contrast to Aarti’s more principled approach.

Indu Sarkar (2017) is set during the Emergency, and shares political DNA with Aandhi. It tackles censorship, resistance, and personal courage in politically repressive times. While Aandhi was subtle and allegorical, Indu Sarkar is more direct and didactic.

In sum, to end this admittedly lop-sided comparison of two films on a similar theme made 50 years apart, Aandhi offers a timeless, introspective look at the personal costs of political life through allegory, while Emergency provides a direct, albeit seriously debatable, depiction of a pivotal period in India’s history.

They do make good films these days. But causing an Aandhi (storm) is something else.