When one of the senior most leaders of the Indian

National Congress, Ghulam Nabi Azad, recently said that the party was at its

“historic low” and that if elections to appoint a new leader of the Congress

Working Committee (CWC) and other key organisational posts were not held soon,

it could mean that the Congress could continue to sit in the Opposition for the

next 50 years, the furore his statement caused was not unexpected. Such voices

of dissent are not common in the Congress party and, expectedly, a Congress

leader from Uttar Pradesh quickly demanded that he be ousted from the party.

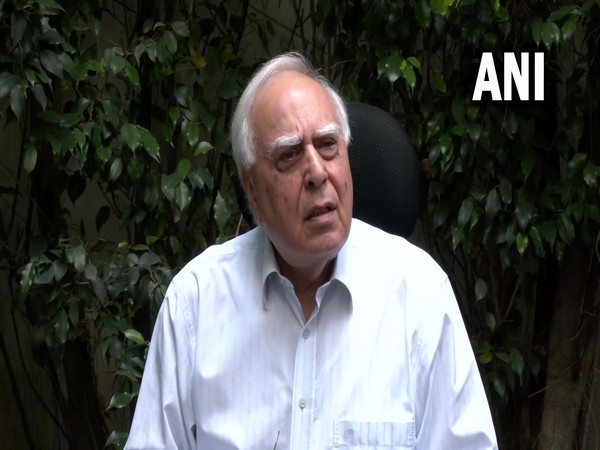

But Azad, who is the current leader of Opposition in

Rajya Sabha, and has held key posts as a Cabinet minister, and as a chief

minister of Jammu & Kashmir, like the young child in the Hans Christian

Anderson folktale, The Emperor’s New Clothes, was telling the blunt truth.

Decimated in the parliamentary elections of 2019, the Congress has been plunged

into a crisis like it has been never seen before. Its leadership, still

controlled by the Gandhi family—Ms. Sonia Gandhi continues as the party’s

interim president after her son, Rahul Gandhi, stepped down from the post in

2019—has lacked decisiveness and several party leaders, have either left the

party to join the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (notably Jyotiraditya Scindia),

or have dissented against the Congress party’s leadership.

In late August, 23 senior leaders of the Congress

party, including five former state

chief ministers, members of the CWC, MPs, and former central government

ministers, wrote to Ms. Gandhi calling for sweeping changes at all levels of

the party. The letter focused on the erosion of the party’s support base; and

loss of support from among India’s youth, who make up a substantially large

proportion of the nation’s electorate. The letter, in effect, was a sharp

indictment of the party’s leadership.

When Rahul Gandhi took

over as the Congress’s president in 2017 it was in line with the sort of

dynastic leadership lineage that one has come to expect in the party. The nadir

of Gandhi’s short-lived tenure—he stepped down in less than two years—was the

second defeat of the party he was leading at the hands of the BJP in 2019.

Since then the Congress, already nearly marginalised after the 2014

parliamentary elections, which it also lost, has become a faint shadow of what

it was. Among India’s 29 states, the party is in power in the states of Punjab,

Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan where the party has majority support. In Puducherry,

it shares power with alliance partner, Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), the

regional party. And besides, simmering dissent within the ranks of its central

leadership, the Congress has also lost much of its direction.

Partly that has

happened as a side-effect of a series of debilitating electoral defeats; but it

is also the lack of a decisive leadership that has weakened and made it

rudderless. The contrast between the two central parties is stark. The strength

of the BJP leadership has never been greater than it is now. The Congress’s, on

the other hand, has never been lesser than it is now.

The Congress may have

missed an opportunity to revamp its leadership three years ago when Ms Gandhi

stepped down and a new president was to be appointed. As it happened, it was

her son who succeeded her. And that might have been the most serious wrong move

by the party to create a strong leadership. For Rahul has never really

demonstrated his ability to be the leader of the party. His track

record—whether it is in leading an electoral campaign or strategy, or in

restructuring the party—has been lacklustre to put it mildly.

Back in 2014, before

the parliamentary elections, this author had written in a column for an Indian

newspaper that the Congress had done a wise thing by not naming Rahul (who was

then the party’s vice-president) as its prime ministerial candidate. The

argument that I put forward was that he was not ready for the role. And

although wishing that the Congress party will come back to power when the next

parliamentary elections are held is, at least for now, in the realm of fantasy,

Rahul still isn’t ready for that role. Then and again in the 2019 elections,

the BJP went to the polls with a strong prime ministerial candidate, Narendra

Modi, and won both times.

The thing is that the

Congress has never really looked beyond the Gandhi family for its top

leadership position. In 2017, Rahul took over from his mother; in 2019, when he

stepped down, his mother became interim president, a position she continues to

hold even as dissent, and calls for a new leadership are welling up from within

the party ranks. It is true that the Gandhi family has acted like some kind of

glue that keeps the Congress party together. The family’s writ runs large in

the party and dissent has been discouraged. Probably not any longer.

The letter by senior

leaders; Azad’s recent statement; the resignation of several leaders (some of

them to join the BJP) all of this point towards one thing: the Congress cannot

exist in the manner it has been for so long. A non-Gandhi leader is what the

party needs most now. But even if it finds one, that person has to enjoy the

autonomy and freedom to change how the party organises; how it functions; and

how it strategises.

The first step would be for its current leadership to

heed the voices of reason that are surfacing from within. Its most important

leaders, some of whom have much more successful political achievements than,

say, Rahul Gandhi, have demanded changes in the way the party is led and how it

functions. For Ms Gandhi, as interim president, that is the writing on the

wall—in clear and bold letters. The second thing for the party and its main

movers is to realise that the climb from where the party has fallen is going to

be a long and very arduous one. The morale of its grassroots-level workers is

low; dissent has spread among its leaders in various states; and the BJP has

strengthened its position over the past six years that it has ruled at the

Centre.

The Congress’s comeback, if the party reads that

writing on the wall, is going to be slow, and often not painless. And, if those

warning signs go unheeded, then what once was India’s all-powerful national

party could hurtle towards extinction.