Classical literature and cinema are full of stories

about stoic and steadfast human struggles against poverty, homelessness,

displacement and hunger; as much as the ritualistic tragedy, and the inevitable

defeat of humanity and humanism. So how does the life unfold as cinema and

literature, tragic as it is, in the time of lockdown and pandemic?

You may read Munshi Premchand’s Sadgati, among others. You may read Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Poor People. Or else, you can simply watch three classics in black & white of our turbulent times: Do Bigha Zameen by Bimal Roy, about a landless farmer’s ordeal in Calcutta; Bicycle Thieves by Vittorio de Sica in war-torn Rome; and, of course, Pather Panchali by Satyajit Ray and written by Bibhutibhushan Bondopadhyay. In the last shot of Ray’s first film, abject poverty forces a poor Brahmin family into exile; their migration begins on a bullock cart, even as a snake slithers into their abandoned ‘home’.

For those who might find ‘this kind of cinema’

unpalatable and unnerving, there is Modern Times by Charlie Chaplin, set up

in the backdrop of the Great Depression in Europe, where hunger, homelessness

and poverty stalked the continent, even as the seeds were being sown for the

rise of fascism in Germany and Italy. And, while, you might laugh, and roll

down with amusement, you might actually observe that the underlying theme is

really not so comic! Not only does this film anticipate the ‘big brother is

watching’ and Doublespeak syndrome, the Surveillance State and the ruthless

capitalist machine in another epical classic penned by George Orwell – ‘1984’,

it actually graphically depicts the mass unemployment stalking thousands of

workers and the sheer brutality of the mechanical machine.

In one interesting scene, a bumbling Chaplin, as usual enjoying himself thoroughly, is being chased by a bunch of utterly bumbling cops. So he falls into a gutter. As he emerges from the gutter he finds himself at the vanguard of a worker’s march on the streets. He quickly picks up a red flag and starts marching right in front – as if he is the leader. In fact, he too is a jobless worker, a citizen in exile, a condemned nobody, in a general realm of utter despair.

Cut to the present scenario in urban India.

In a dark irony, the real life parallel cinema

has gone ‘viral’ at several crossroads in present times, even during the

emptiness and helplessness of the lockdown. It’s mostly about poverty, hunger,

homelessness and migration. And it stalks about 40 crore unorganized workers in

the vast, sprawling and unaccountable informal sector of India, employing as many

as 93 per cent of the workforce, who are virtually invisible and ghettoized,

practically without any fundamental or trade union rights, no health insurance,

no maternity leave, no provident fund, just about nothing. Half of them are

women, and a majority of them are Dalits and most backward classes/castes. They

are basically outside the market, except as ‘free labour’, and Indian citizens

outside the directive principles of the Indian Constitution.

Tens of thousands of them started marching soon after the Prime Minister’s second 8 pm monologue, with just about three hours given as time in the thick of night to restore normalcy in life and to organize and plan ahead. Most of them had no option since they were thrown out of their homes and jobs, and their day-to-day life of basic, minimum subsistence outside all social security schemes or a future.

So, while swanky cars zipped past them, and people watched this Reality TV from high-rise balconies on expressways, the poor started walking to unknown destinations from where had migrated to look for work, many of them barefoot, children in tow, often sharing the burden. It was the long march, from here to eternity, under a scorching sun; hungry and thirsty women, mothers, children, walking along.

The Prime Minister’s unplanned and rather

insensitive lockdown anouncement had failed for the whole world to see. The

virus was all over the place, in human exodus and exile, in mass migration, in

the sheer mass tragedy unfolding on the streets and highways.

A girl posted on social media that she stopped

her car and asked a family moving on foot if they needed anything: biscuits,

water? A young couple with two little ones. The woman is holding a sack on her

head with her belongings – the sack has a name – ‘Santushti’. The man is

holding a larger sack on his head – it too has a name, ‘Good Times’ or acche din. The woman smiled with

gratitude, and said, “Nahi didi, hamare

paas abhi toh hain. Aap kisi aur ko de dena…” (No sister, we have food as

of now. You give it to someone else.)

Hundreds of workers who were not allowed to

march, found shelter on the banks of a dirty Yamuna in the capital of India in

recent times, not far from the citadels of power, under a concrete flyover. Most of them have not got even one meal a day;

and they have no work, no money, nowhere to go. They are trapped, even as NGOs,

students, good citizens try to reach out. There are innumerable and scattered

stories about the fate of these invisible men and women across the cities in

India, especially around industrial zones and townships.

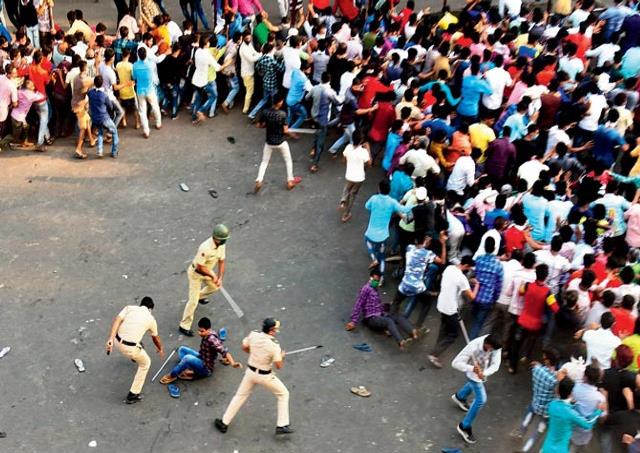

In Surat, there have been repeated and angry pitched battles of the workers with the cops. This is the textile hub of India, apart from its famous diamond industry. Surat is in crisis anyway since demonitisation and GST, with its small scale industry in a black hole. And they were/are all die-hard Modi supporters.

In Bombay, hundreds of workers came out, without

any bag or luggage, at Bandra railway station, saying that they just want to go

home, that life here is just not livable, that there is no hope left now.

Thankfully, the cops did not beat them up, though FIRs have been lodged against

scores, including a ‘trade union’ leader who gave a call to the workers to hit

the streets near the Bandra railway station. Indeed, not to miss another

diabolical and sinister chance, the usual ‘Hindutva’ TV channels quickly found

a reason to give it a communal dimension, just because there was a masjid close by. They did not even

bother to check if the masjid was

actually providing food to the workers.

A reporter with a TV channel too has been

arrested for giving the fake news that special trains will take the jobless

workers to their native places. Indeed, with the kind of fake news circulating

all over, like an epidemic of sorts, especially by the same TV channels

compulsively, obsessively and without an iota or concern for media ethics, it

is anybody’s guess why they are not being hauled up.

Surely, there are stories within stories. It’s a Do Bigha Zameen for the unwashed masses,

yet again. Surely, in this Pather

Panchali, the Song of the Road, there is neither melody, nor joy.