Forget the Covid pandemic; forget the economic downturn; forget election debacles or political crises. The biggest test that the Modi regime, soon to turn seven years old, has been subjected to during its ongoing tenure is the deafening protests by farmers against the changes that the Indian government has sought to bring about in the way farmers are able to grow, market, and price their produce.

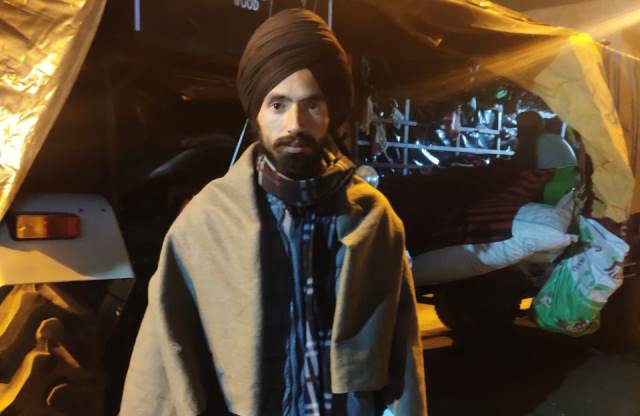

In the last three months, protests by farmers have reached a crescendo. On January 26, which was India’s 72nd Republic Day, a group of angry farmers deviated from their designated protest route, tried to storm the historic Red Fort, and clashed with police. As that was happening, a few kilometres away, Prime Minister Narendra Modi was presiding over the official Republic Day celebrations on Delhi’s Rajpath.

At least 70 farmers have died during the raging protests against three laws that the government has passed. And, the protests, which began in the northern state of Punjab, have now spread across the country. What makes the controversial farm laws and the protests against them such a big trial for Modi and his government? For an answer, let us first recapitulate the new laws and their impact.

The three new farm laws change decades-old policies regarding procurement and storage of farm produce. One law permits the setting up of mandis (or trading places) that are de-regulated from government control—that is, where farmers can sell directly to all traders at prices they negotiate rather than to only government licensed traders; another law permits farmers to enter into contract farming through deals with corporate entities and to grow whatever crops they decide to under contract; and the third allows traders to stock produce with less restrictions than at present.

ALSO READ: Are The Farm Laws Legal?

The government’s rationale for these changes is ostensibly this: they will enable farmers to sell at whatever prices they want and to anyone they want to; and to be able to enter into contracts that could assure them regular and steady streams of income. From the ongoing protests, which have been escalating, it is quite evident that the farmer community has not bought this logic.

Farmers and their supporters feel that especially the smaller farmers whose incomes are meagre will be hit by the new measures. First, their produce volumes are too small for them to be able to negotiate prices with traders who aren’t regulated—thereby they would likely be exploited. Second, although the government has assured that the mandi system will not be dismantled, farmers fear that the new “unregulated” mandis will consequently do exactly that, and that small and medium farmers will suffer. Lastly, contract farming, they fear is a way of giving the corporate sector easy access to the farm sector.

Nearly 60% of 1.3 billion Indians depend either directly or indirectly on agriculture, which accounts for 18% of the GDP. But the farm sector is severely skewed. Almost 70% of Indian farmers own land that is less than 2 hectares (20,000 sq. m) in area. And as much as a quarter of Indian farmers subsist below the poverty line. Moreover, because of lack of alternative employment opportunities millions of Indians depend on the farm sector without really contributing to productivity.

Against that background, reforms in the agriculture sector are overdue. But changing the system of pricing and procurement of crops without other structural changes in the sector cannot be a solution. In fact, it could lead to further suffering for millions of Indian farmers. The farmers’ protests are a sign of how acute the problem is. And, for the Modi government, it is the most critical test that it faces in its tenure thus far. In 2016, Prime Minister Modi announced a sudden decision to demonetise large currency bills. Ostensibly, it was with the intent of limiting or detecting unaccounted money in the system. What resulted was: widespread suffering for small traders, daily wage earners and other large segments of the population that operate in the “cash economy”. Those with so-called unaccounted wealth went largely unscathed.

Demonetisation was certainly a critical test that the government faced. But its effects—on economic growth and on small businesses—were not nearly as serious as the impact of the new farm laws have been. Over the last few days, the clashes between farmers and the authorities have turned more violent, particularly in the areas surrounding the capital city of Delhi. The authorities resorted to blocking of Internet in various areas around the capital and neighbouring states—purportedly in efforts to curb social media interactions. Police resorted to tear gas and baton charges against thousands of protestors. Already, the ripples of what is happening in India have reached the world outside. And questions are being asked about the true value of democracy in a country that prides itself as being run on the highest democratic principles.

ALSO READ: The World Is Taking Note Of Indian Farmers’ Protest

The police and authorities’ action against famers’ protests have also spilled over to affect others. A freelance journalist, Mandeep Punia, who was covering the protests, was arrested on the border between Delhi and Haryana last weekend. He was granted bail after spending two days in custody and much outrage. Others have had cases filed against them for reporting or broadcasting news that has been considered “anti-government”.

But the more serious issue is that India’s mainstream media has almost been rendered toothless in recent years, particularly after the current government came to power in 2014. It does not require media experts to see how the majority of mainstream TV news channels and print publications largely avoid taking on the government and critiquing its policies. When they choose to do so the critiques are of the milquetoast variety, tailored not to ruffle the feathers of those in power too much. In any democracy, the role of the media as the fourth estate should be that of a watchdog. In India, at least when you look at it from a dispassionately distanced point of view, it may seem that the mainstream media is more of a lapdog.

For the Modi government, the farmers’ agitation has other possible consequences. The farm sector’s voters aggregate as the largest block during any election. And although the government at the Centre is safely ensconced for the next four years, there are crucial state elections that are due and those could be impacted by which way farmers decide to vote. Also, if the agitations escalate and food supplies are affected across India, they could have other economic consequences such as inflation and distribution bottlenecks. Already reeling from the impact of the Covid pandemic, the economy could be hit further. For the Modi government the farmers’ agitation over the controversial laws could be something that could bring it to its knees.