Nearly

six decades on, generations of Indians remain angry at the military debacle that

China inflicted in 1962. It casts a long and deep shadow on bilateral and

regional ties. India is compelled to strategize for a two-front war against China

and Pakistan, the two “iron brothers”. Billions are spent on raising mountain

divisions and airbases.

The

border dispute that triggered it, however, remains unresolved. Mutual distrust

persists in all spheres, and is unlikely to go, as China surges way ahead as a

global player. India is unable to match.

As present-day Indians seek to review, even rewrite, unpalatable past events, “sixty-two” rankles. A new book raises afresh an old question: How far Jawaharlal Nehru and his Defence Minister V K Krishna Menon, the two perennial villains, were responsible?

“The

truth is far more complex. Both made mistakes, but to blame them solely would

be simplistic,” says Jairam Ramesh in ‘A Chequered Brilliance: The Many Lives

Of VK Krishna Menon’.

He writes,

“warts and all”, about their faulty political, diplomatic and military

assessments, but also of tub-thumping politicians who opposed any compromise, even

talks, on the British-drawn India-China border. They included Finance Minister

Morarji Desai who rejected pleas for increased defence budget citing Mahatma

Gandhi’s ‘ahimsa’.

They

were also the ones who pilloried Nehru-Menon the most after the conflict. “If

he doesn’t go, then you will have to go,” Mahavir Tyagi, senior lawmaker and

fellow-freedom fighter, warned Nehru. Menon had to go.

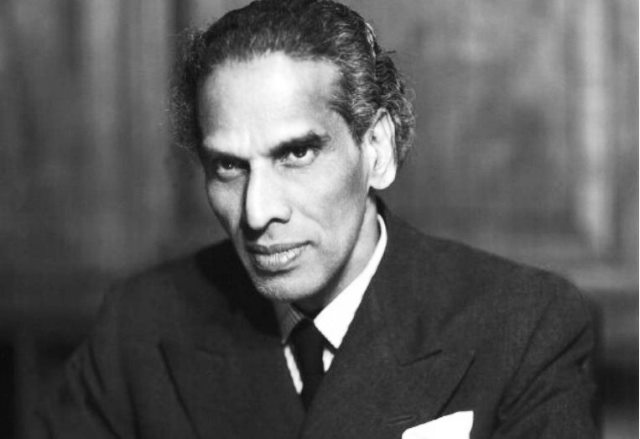

Congressmen

hated Menon’s proximity to and influence on Nehru. He had lived in British

comforts and never went to jail like they did. This legion of Menon’s past critics

agreed that he was acerbic, even arrogant, highly opinionated and disdainful of

others’ views.

Even

now, Kunwar Natwar Singh, diplomat-politician and one-time foreign minister, declares

while reviewing this book: “Menon does not deserve a 700-page biography.”

Ramesh,

a Congress lawmaker and former minister, is no apologist either of the duo and

other actors of that era. He records Menon’s bad vibes with the military and his

interfering in their working. His elevating a favourite, Lt. Gen. B M Kaul, to

fight the Chinese was among the most glaring of his disastrous decisions.

Although

“not romantic”, the two were empathetic towards China. They would have liked a

negotiated settlement of the border dispute. Menon, indeed, had a specific

roadmap. But they were up against the conservatives. Also, they grossly

miscalculated the Tibet factor after giving asylum to the Dalai Lama and Mao

Zedong’s compulsions to use conflict with India for domestic political gains.

Resurrecting

Menon 45 years after he died, utlizing heaps of archival material, Ramesh

traces his role as the principal spokesman of India’s freedom movement in

Britain and as a minister post 1952 after his controversial tenure as the high

commissioner in Britain. Ramesh thinks Nehru’s mistake was to be his own

foreign minister and have Menon as his defence minister. Both areas suffered. When

Menon toured the world as his envoy and was busy defending India at the United

Nations on the Kashmir issue (including his record-breaking nine-hour speech) files

piled up in the defence ministry.

His

focus is on Menon, but he also creates an equally mesmerizing image of Nehru. Both

had a common guru in Professor Harold Laski. Both were democrats. Both held similar

world-view. Both were deeply suspicious of the West, trusted the Soviet Union,

but being Fabians, were not communists. Calling himself an archival biographer,

Ramesh does not pre-judge events whose conclusions are already well-known, nor

does he intrude by making moral affirmations.

As

individuals with differing backgrounds, he says, the two enjoyed great mutual

trust. Both were creatures of colonialism and products of British education.

They spoke and wrote immaculate English — Menon, only English. But they fought

colonialism and the British rule.

Their

detractors accused them of being ‘Westernized’, while the West distrusted the

two socialists. Menon was a bigger target, considered close to the British

Communist Party, the only British group that espoused India’s independence.

Was

Menon, then, Nehru’s alter ego? No, Ramesh insists. He was Nehru’s

“shock-absorber.” This is as sympathetic as people have been decades after the

two have gone, leaving behind a flawed legacy.

They are, however, viewed differently. Menon never recovered from 1962 – he never defended himself. Nehru died a broken man 18 months later, but partly thanks to his daughter and grandson ruling for long years, remains the most iconic figure of post-independence India. Today’s rulers, however, demonize him.

Post-independence,

Menon’s persuasion of Nehru led to India joining the British Commonwealth and

play a leading role in the forging of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM).

Strangely, one was considered an anti-communist front of former British

colonies while India’s NAM advocacy pushed it close to the Soviet-led Bloc. In

this century, India pays only lip service to the NAM and is lukewarm to the

Commonwealth.

Menon’s

role was not all evil. In the 1950s, a newly-independent India “got a much

higher profile than its might and punched well above its weight”, taking

initiatives to resolve the crises in Korea, Cyprus, Vietnam, the Suez,

Indonesia and West Asia. Menon conferred with some of the most prominent

figures of the mid-20th century – Nasser, Tito, Fidel Castro, Chou En Lai and Ho

Chi Minh. John Kennedy, however, didn’t like him. Time magazine that never had

a kind word for him, called him “India’s tea-fed tiger.”

Ramesh

records how Menon, a bachelor, charmed women of the British elite. While many

admired him, Pamela Mountbatten found him “most cynical.”

Menon’s

role in the domestic affairs was significant, Ramesh says, citing his little-known

contribution to the merger of princely India along with V P Menon.

Menon

had drafted the Preamble to the Constitution with terms ‘secular’ and

‘socialist’. But Nehru, heading an all-party government that had Syama Prasad

Mookerjee of the Hindu Maha Sabha, saw no consensus on them. He asked Menon to

“go easy”. Inserted only in 1976, in the 42nd amendment, they are part of the

Preamble currently being recited across the country by those protesting the Citizenship

(Amendment) Act. But a consensus eludes even today.

Post-Nehru,

the Congress shunned Menon. Although Indira Gandhi regarded him, it declined him

party nomination. Menon fought elections as an independent – lost twice, won

once.

Times

have drastically changed. Shiv Sena denigrated all South Indians in Mumbai as

‘outsiders’ during an aggressive election campaign that felled Menon in 1967.

Till then, Menon, a Keralite, would address large crowds, in English, at

Mumbai’s iconic Shivaji Park. The present-day Maharashtrian, with Sena in

power, cannot even imagine this.

In

his last days, Menon remained sought-after. The BBC correspondent assigned to

report the 1971 India-Pakistan conflict in the Sindh-Rajasthan theatre began by

interviewing Krishna Menon. “You cannot conceive of a war in South Asia without

that,” he told me.

Little

is known about Menon’s love for the young. Students in the 1960s heard him in

awe, over endless cups of tea. As one among them, I found it was difficult to

keep pace on either tea or talk. He was, as Ramesh records, a humanist.

The writer can be reached at mahendraved07@gmail.com