The Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) was a small unit under Jawaharlal Nehru that grew with time and with each prime minister. Little is known of its current strength and those who man it. But undoubtedly, under Narendra Modi’s stewardship, it is the strongest entity governing the country.

A common thread runs through them all. As happens in any parliamentary democracy, a PMO grows at the expense of the Cabinet Secretariat. Over the years, the PMO has become the instrument through which decisions on complex issues are taken and relayed to the right authorities to be enforced. And till that is done, the officials are on their toes.

They may pertain to anything – administration, politics, Centre-state relations, foreign and security affairs. In a sense, the PMO oversees the working of the entire nation. And since it has become a top-down process, mistakes occur and fault lines develop in a vast polity like ours.

Its work is being written about and discussed. The Narasimha Rao years have been written about by his biographers and recently, by his spokesman, S. Narendra in India’s Tipping Point. The Vajpayee years were analysed by the late Shakti Sinha. Manmohan Singh’s decade was treated in an erudite manner by Sanjaya Baru but ended up becoming an election-eve film that did little credit – forget the filmmaker — to the supposed protagonist.

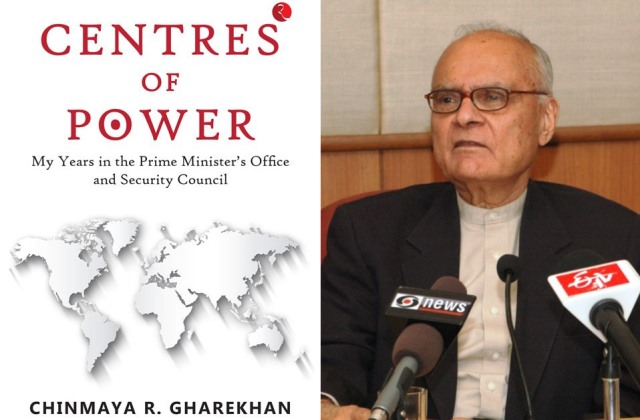

At a time when the current government does not exactly heap praise on the Nehru-Gandhis, it is interesting to read how their PMOs dealt with challenges faced nearly four decades ago. But it confirms the common trend. Ambassador Chinmaya R. Gharekhan, who worked for them (1981-86), notes that “the concentration of power in the PMO has tended to depreciate the expertise of the civil service machinery.

“In a bureaucracy, access is everything” and having the PM’s ear inspired a feeling that he could “influence decisions even more than the foreign secretary,” he says in Centres of Power: My Years in the PM’s Office and Security Council. A year after he left the PMO, in 1987, Rajiv announced the sack, at a press conference, of Foreign Secretary A P Venkateswaran.

Gbarekhan says the system ensures the politician’s supremacy: “Even puppet politicians are politicians first and puppets later”.

Proximity to PM matters. Shakti Sinha was the “first and last man Vajpayee would see in the day through much of the mid-1990s — during his 13-day tenure in 1996, his stint as leader of opposition between 1996 and 1998, and then during the critical 1998-99 years when India went nuclear, embarked on ambitious reforms, and fought and defeated Pakistan in Kargil.” The reviews of Sinha’s book Vajyapee: The Years That Changed India say he understood the PM intimately during the numerous meals the two would share, alone — in total silence.

Those who reviewed Gharekhan’s book released last month, include K. Natwar Singh, a former foreign minister and Krishnan Srinivasan, a former Foreign Secretary. Srinivasan confirms two little-known things. Narasimha Rao mistakenly did not appoint Gharekhan as the Foreign Secretary. More importantly, when Natwar Singh resigned as Foreign Minister in 2005, Sonia Gandhi wanted Gharekhan to take over. This did not work out.

Gharekhan enjoyed working with the Gandhis. His accounts and anecdotes are both revealing and refreshing. Indira wanted to be accepted as a stateswoman and hoped to get a Nobel. And Gharekhan headed a committee to canvas for the prize. This was “as bizarre as that sounds. Clearly, some in high places in Delhi were, then as now, remote from reality.”

She did not share Nehru’s ideological affinity for Russia, was pro-British and was solicitous over British visitors, though she disliked the Commonwealth, “perhaps because in that forum several heads of government indulged in very plain speaking.” She cared about her coverage in the media, especially the Western press.

ALSO READ: Narasimha Rao – A Rebel And A Reformer

Gharekhan speaks of how the Americans were “most excited” about Rajiv Gandhi’s assumption of office and took advantage of Rajiv’s inexperience to flood Delhi with a host of envoys of dubious quality. That, one would surmise, is typical diplomacy, and not confined to the Americans.

While Indira changed drafts of statements, messages and speeches “like a sub-editor”, Rajiv simply had no time and patience for them. He did not like to be told how his mother worked or would have worked, on a particular issue. But both were trusting and caring of their officers. Indira would instruct staff to prepare ‘khichdi’ since Gharekhan had a bad tummy.

Gharekhan got on well with Indira. From time to time both would converse in French to the discomfiture of officers and ministers. But all that has not prevented him from being critical of the two bosses.

That she was superstitious is well-known, and so is her immaculate dress sense. Gharekhan had to reassure her once that her saree was perfectly worn, except a “little high on the left.” And as she corrected it, she would ask the poor official to “look away.”

Where else would anyone get a boss who keeps a tab of the officer’s cultural pursuit, outside of official work? Indira would listen to Gharekhan’s Hindustani Classical rendering on the radio and convey her appreciation of the performance. This is the stuff of which a good book is made.

Natwar Singh notes a word from Gharekhan that has a message for the present dispensation: “1962 had done harm to India and to Sino-Indian relations. All that changed when Deng Xiaoping told the Indian Prime Minister to leave the border aside and develop good neighbourly friendly relations in other areas like trade and tourism, exchange of students etc. From 1988 to 2020 there was no conflict between the two countries.”

Considered a ‘progressive’ in the PMO, despite his proximity with both the PMs he served, Gharekhan disliked Indira’s invocation of family heritage – “the emphasis on the family did not sound decent in a democracy”, adding, in another context, there “was no half-way house between democracy and dictatorship”.

What worked for Gharekhan was “my non-offensive, non-combative style”. It enabled him to ride the contradictions inherent in the system he worked within. His swan song before he left for the US to spend his remaining years shows him as a calm, composed and unruffled diplomat. We are talking of a different era.

The writer can be contacted at mahendraved07@gmail.com

Read More: lokmarg.com