Providence has willed contrasting twists for the “Battling Begums of Bangladesh.” Former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina is exiled in India, facing a death sentence back home. Her arch-rival, Begum Khaleda Zia, the ailing two-term premier, battling for life, has the nation’s sympathy.

Bangladesh is election-bound, and Zia’s Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) is the front-runner. This explains why the ‘establishment’ led by Chief Advisor Muhammad Yunus is working feverishly for her recovery, declaring her a ‘VIP’, after doctors’ advice that she is too weak to travel to London for advanced treatment.

India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi has joined in with ‘concerns’ about her health and has offered any help Dhaka may require, ignoring bad vibes, on the day a probe panel alleged that 16 years ago, India was ‘involved’ in the mass killing of the neighbour’s border police in a mutiny. The charge is preposterous because Hasina had just assumed power, defeating both Zia and military machinations in an all-in election. Besides Hasina’s exile, this impacts the current election campaign. The perennial India factor is also Providence’s will.

London is where Zia’s elder son, Tarique, is exiled. Although he has no Bangladeshi passport, his homecoming poses no problem since the courts have cleared both mother and son of corruption charges.

Will Khaleda, 80, having multiple ailments, become the third-time premier if her party wins the elections next February? It will be tragic if she cannot, after many years of imprisonment and sufferings inflicted by the Hasina government. In that case, Tariq, 60, may lead Bangladesh. Like Yunus, targeted by Hasina, returned from the United States after student protests felled Hasina in August 2014. Providence, Providence, Providence!

The way for either Zia to come to power is paved by the ousting of the Hasina-led Awami League from the electoral arena. In Bangladesh, politics is a zero-sum game. If you win, you rule. If you lose, you boycott and protest, face court battles and imprisonment.

The Awami League ban reminds one of Hasina’s ban on the Jamaat-e-Islami. It was accused of ‘collaborating’ with the erstwhile East Pakistan regime in 1971. It is now a footnote in contemporary history as the Jamaat is back in the political mainstream and may again align with the BNP in the February elections. And so is Pakistan back in what was once its eastern province.

To return to the two women and the family legacies they inherit. Hasina’s father, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, was assassinated in 1975. Zia leads that of her husband, General Ziaur Rahman, also the President who was gunned down in 1981. The rival legacies have clashed for political primacy and power, of which bad personal vibes are a natural outcome.

The only time the two Begums – Hasina never uses this prefix while Zia does – collaborated as part of a larger political alliance was in the late 1980s, to oust General H M Ershad. In the election that followed in 1991, Zia won, and Hasina lost. The tables turned in 1996, but Zia was back in power in 2001.

Rivalries sharpened all these years. One pushed the other to jail with graft charges. Dhaka’s Zia International Airport was renamed after Shah Jalal, a revered saint. Three attempts were made on Hasina’s life. She paid Zia back in the same political coin during 2009-2024.

They rarely met or shared a public platform. Among the more prominent was Hasina’s visit to the Zia home to console the death of younger son, Arafat. The prime minister waited, to be told by Zia’s staff that, under sedation, she was resting and unable to receive her.

Both women were out of power in 2006-08 when the military-backed caretaker government did not hold the elections as prescribed under the Constitution. That government failed to exile them. Hasina, in America to meet her family, was denied re-entry. She fought her way back home from London. Public opinion in Britain helped. Khaleda, too, offered freedom from jail and immunity for her sons, but refused to be exiled. The bizarre “minus-2” attempt failed, and Bangladesh was back to “Battling Begums”.

In fairness to Zia, she did not express joy at Hasina’s ouster. Her party, advocating “inclusive politics”, opposed the Awami League’s ban. Its swift switch-over has come only after it became clear that the Yunus regime is bent on a vengeful course against Hasina.

The prayers and public sympathy for Khaleda, with Yunus also joining in, are coupled with a special prayer organised at the Dhakeshwari temple in Dhaka, Bangladesh’s most prominent shrine of the largest minority community. It reflects, besides respect for a woman leader, which is typical of Bangladesh but rare in the Islamic world, how the political wind is blowing.

Perhaps, it is appropriate for this writer to record some memory flashbacks, having worked as a journalist in Dhaka. Both women are light-eyed and beautiful in a conventional Bengali/Asian sense.

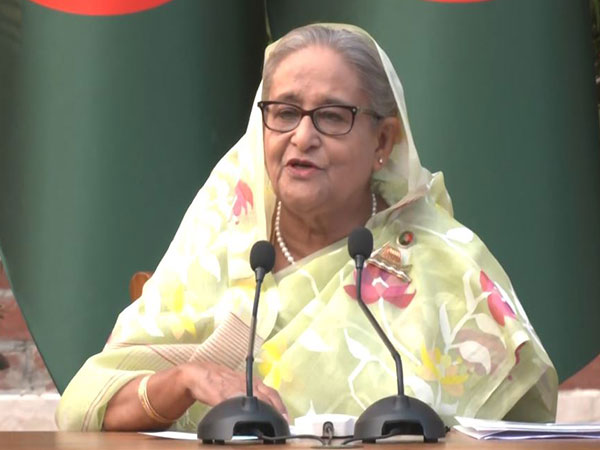

In the years following independence, a bespectacled Hasina alternated between a housewife and a low-profile daughter of the prime minister who took an interest in students’ politics. Deeply political, she would watch her father at work. Comparisons were drawn, in whispers, though, with Jawaharlal Nehru and Indira Gandhi.

Khaleda was a vivacious army wife, then in her late twenties, the cynosure of many eyes at diplomatic events as she walked with her soldier/freedom fighter husband. As the army’s Number 2 man, he was rising in influence. Mujib was known to have been fond of the couple.

If Hasina returned to active politics on her return to Dhaka from her earlier exile in New Delhi (1975-81), Khaleda was compelled after her husband’s assassination in May 1981, to lead the BNP that he had founded.

Like any Bangladeshi over the years, they figure out India. The rival legacies have meant that Hasina was, and remains, friendly to India, paying a political cost, being maligned by her critics at home and in the West. That has also shaped the Awami League’s relatively secular politics. Khaleda carries no such baggage. Like her husband, she distrusts India.

Muchkund Dubey, one-time Indian High Commissioner to Bangladesh and later Foreign Secretary, records that he had wanted then Prime Minister P V Narasimha Rao to visit Dhaka and mend fences with the Khaleda government. That visit did not work out. Zia’s visit during the Vajpayee era was also a low-key affair as India was concerned about the rise of Islamist terrorism under her charge.

As Delhi tackles Dhaka’s pressures to return Hasina, who is viewed negatively by the Western world, it must also prepare for the near future, assuming elections are held and will mark the rise of the Zia family. These are radically changed times, when regional and global trends in and around southern Asia pose complex challenges.