Few would deny that the multi-millionaires who control social media outlets have garnered more power than is good for them or for ordinary citizens.

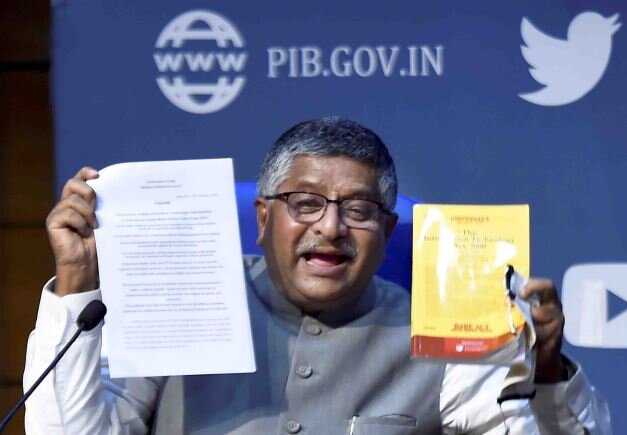

At first glance the Information Technology (Guidelines for Intermediaries and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules 2021 introduced by the Narendra Modi government appears to be a brave attempt, where others have failed, to bring social media giants into line with other forms of publishing. Facebook, Twitter, Instagram etc have always insisted that they are merely platforms on which others publish material and so cannot be held responsible for any content that appears.

Public attitudes towards this hand-washing has shifted with the realisation of how damaging ‘fake news’, misogynistic trolling, racism and pornography can be not only to individuals but also to the body politic.

The advent of ‘social’ media has not only enhanced economic activity but also encouraged freedom of expression. It has democratised communication, bringing both heat and light to public discourse. But that invariably means that there is a dark side. There are plenty who will abuse this freedom and who do not or will not recognise that their rights extend only so far as they do not impose on other people’s. There are limitations to freedom of speech which it may require impartial adjudication in law.

One welcome element of these new Rules is the provision of a complaints mechanism, well-advertised and based in India, so that individuals who are maligned may seek redress.

The basis for such complaints has to be common terms of reference and the suggestion is that social media should comply with both the Press Council of India Code and the Programme Code of the 1995 Cable TV Network Regulations.

But that is one of the first major stumbling blocks. If the platform is not the originator of material how can the operators ensure that user-generated content is compliant? In effect they are being asked to take responsibility for literally moderating all material produced by people who may never have heard of these Codes and certainly will have played no part in devising them.

The new Rules require platform operators to advise users they must not flout the constraints placed on them by such Codes, and to swiftly remove content that does not comply, under orders from a court or a government agency.

And that is another major sticking point.

While the Rules claim, without irony, to be introducing a ‘self-regulatory system’, ultimate power to both define compliance and determine what is and is not acceptable rests with the government.

This applies as much to professional purveyors of news as it does to user-generated content on social media.

Since it is never difficult to find someone willing to complain about items that are critical or in any way challenging of those in power, this has an almost automatic ‘chilling’ impact on publishers of news and views. Self-censorship is quickly seen as the route to survival, and ‘state security’ quickly supersedes the public interest. Autocratic regimes from Belarus and Egypt to Vietnam and Zimbabwe have demonstrated how effectively that can control the news agenda.

The Cybersecurity Administration of China may illustrate the value to power elites of an overarching regulatory regime, but in the murky world of online communications control of news need not be so overt. Ostensibly Vietnam’s Law on Cybersecurity is designed to prevent harm to ‘national security, social order and safety, or the lawful rights and interests of agencies, organisations and individuals’, but in practice it is designed to keep all online traffic in line with the government’s strictures.

Meanwhile in Bangladesh a draconian Digital Security Act (DSA) has been used since 2018 to clamp down on freedom of expression, with journalists jailed and assaulted for criticising the government.

Something similar is happening in Myanmar where the military junta, not content with ‘disappearing’ journalists off the street, is working on laws to take charge of online content in its bid to crush opposition and identify its critics.

Many may feel relief that under Modi’s model, social media platforms will be expected to take down offensive or sexualised images, but few will happily concede that the government should determine what constitutes unacceptable or derogatory material. The use of key words to identify problematic copy is one of the easiest ways to monitor and thus control content, especially terms which might refer to government policies.

The administrators of global social media platforms may not be best placed to handle the subtleties of cultural differences, but almost inevitably partisan government departments are certainly not the best arbiters of what is and is not acceptable in public discourse.

Having government officials determine those limits is seriously problematic, especially for journalists whose key task is to hold the powerful to account and to turn a spotlight onto the corrupt and the criminal. In a society riven by religious, political and caste divisions, the existence of both independent journalism and an independent judiciary is paramount to highlighting and determining disputes.

The Information Technology Rules 2021 may be a brave attempt to tackle issues that are perplexing societies around the world, but they are also a recipe for creeping censorship which requires robust scrutiny and resistance to ensure that a diversity of opinions and debate are able to flourish within and beyond the state.

There has been widespread criticism of Modi’s plan in the West, where efforts to control the internet without affecting online news content have also hit the inevitable obstacles.

The European Union is currently wrestling with the complexities of devising a Digital Services Act that will harmonise protection for citizens and consumers across 27 countries without curtailing press freedom. Journalists’ organisations have been vocal in their opposition to anything that might detract from their ability to scrutinise governments, investigate corruption and expose crime. They will be watching to see how their colleagues in India tackle the same issue.

(The author is a UK-based journalist and Honorary Director of The MediaWise Trust, a journalism ethics NGO)