Politicians have cyclically tried to lure the voter with a ‘supranational’ identity, not realising that the most enduring character of Indian civilisation is its diversity

Are India’s election results that difficult to predict as many pollsters say? After the 2014 general elections, many pundits have become cautious of declaring outcomes one way or the other. However, Indians, like people anywhere in democracies, do not vote just for roti, kapra, makaan (food, clothes and shelter). Other factors such as vision, identity, belonging and peer pressures also influence their choice. In India, it is the pendulum oscillating between a ‘supranational’ identity and a regional ‘national’ identity that seems to be a considerable factor other than economics.

India is a country of many nations, many religions, many ‘Peoples’ and even many cultures and regions. The first identity and belonging of the average Indian, apart from the metropolitan English speaking class, is their community or region.

Every couple of decades, the ‘rooted’ voter is seduced and drawn out by a bigger vision, a ‘supranational idea’, a collective dream or ‘national’ and even a collective threat. It is promoted or exploited by a maverick leader or slick party machine.

Wars were the one factor that brought people in a huddle and start thinking ‘nationally’. It was a nationalism of negativity, of fear of being taken over again and losing ‘independence’. Wars were not necessarily of India’s choosing until Mrs Gandhi came along.

Mrs Gandhi understood that in the simple majoritarian Westminster type democracy, fissiparous votes could not be relied on to deliver working majorities simply on a platform of economics, particularly as regional parties could deliver economic improvement competitively. There had to be a ‘national’ issue or a crises to rally Indians around.

She precipitated a crises within Congress and found an internal ‘enemy’ to rally the troops. Then came the 1971 war which she started. A victory created a ‘national’ upsurge. But soon it waned.

She then targeted the Sikhs and played communal politics. The Sikhs fell into a trap. They were portrayed as the new threat to ‘Hindustan’ as a country although no real movement for Khalistan existed before 1984. The Sikhs were asking for greater regional economic and political autonomy for all Indian states. 1984 changed that and Congress had a few more years of playing the ‘national integrity under threat’. Votes were almost guaranteed. A paranoia of nation under siege overrode regional identity.

The Sikh factor could not be played for long. Indira Gandhi paid with her life. Although Rajiv Gandhi gained from that after his mother’s assassination wearing saffron clothes among other props to create a national ‘unifying’ vision, he had no ‘national crises’ to speak of after that. Fissiparous politics came back and a coalition of regional parties got into power at the centre as a coalition only to break under their own centrifugality or lack of any ideology keeping them together.

Rajiv was assassinated. Congress cashed on the insecurity and sympathy. Again the paranoia of ‘threat’ precipitated a national surge.

Congress has relied on the metropolitan class sold on the idea that India needs to be non-religious, hence secular like Europe. It successfully portrayed Hindu Mahasabha parties as threat to national unity neutrality and minorities. Its second large vote bank was the Schedule Castes and the third the Muslims. Schedule Castes hate upper caste Hindus and Muslims fear Hindus of the Mahasabha. Congress played this deftly. However, Congress also subtly played the Hindu identity card.

Playing the ‘Hindu’ card after Mrs Gandhi’s death and after Rajiv’s death, Congress unleashed a new unifying force, a revivalist Hindu nationalism. The Mahasabha cashed in on this. Its message was that the Hindu was treated as second class citizen in his own country and was being betrayed by Congress to appease minorities and ‘lower castes’.

This gradually forged a new national identity, ‘Hindu India’ created on conspiracy theories of Hindu neglect and victimhood. Hindus sense of marginalisation was cleverly played by BJP on the national field with the Bania as its most ardent supporter. This is India’s Brexit wave.

The first BJP Government came to power without any coherent vision. Simply hating fellow countrymen, blaming them for invasions that took place 1,000 years ago and a policy of reversing historic conquests of the past is not a sustainable political theory. The Ram Mandir issue in Ayodhya may have translated some sense of historic grievance into a vote bank but it does not give people a positive identity or fill their stomachs.

Fissiparous trends pulled back the vote in favour of Congress as the regional parties were too fragmented to come together. Congress has had a clever way of forging federal tendencies and minority insecurity into a national secular campaign fighting off what it deems ‘regional communalism’ and Hindu communalism. But its game plan is cracking up and it is increasingly having to forge coalitions with the real regional parties to form a ‘national government’ still under the plank of the ‘secular’ as anti-Hindu communal slogan. It is not thriving.

The regional parties of India lack a national political idea that holds their federalist nature in a national coalition for long. People feel comfortable to vote for them only if there is a larger ‘national’ party in the coalition that can lead.

After the first BJP government, politics nevertheless got back to its default mode of being fissiparous and threw up coalitions led by Congress the largest party.

War as a unifying notion is no longer possible. With a nuclear Pakistan, war is a high risk strategy. The neighbours know India’s British templated adversarial political system means the party in Government is tempted to wage a token war to look ‘tough’ and harvest the vote. As insurance they have entered into security arrangements with China or USA.

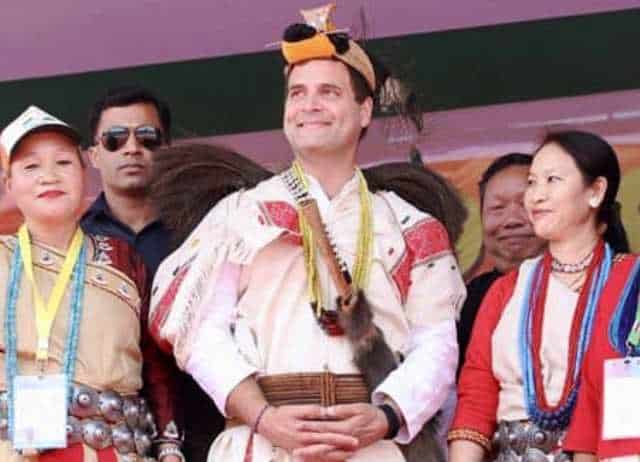

Along came Modi. He cast himself as the saviour to restore Hindu glory and recover from a thousand years bruise of having been conquered and ruled. He was going to put the Hindu on the world map. Above all he was going to show all Indians that in India it is Hindu first, Hindu most and Hindu top. Hindutva replaced secular. Even Rahul Gandhi has metamorphosed into a Hindutva clone, visiting temples in veneration dhoti.

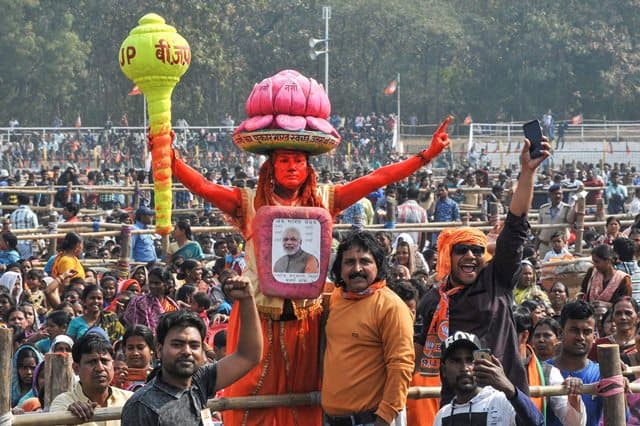

Many Hindus in India began to wear their identity on their sleeves and express prejudices in the open. Hindus outside India became the new Khalistanis, except in this case Hindustanis, annoying NRIs who don’t chant Bharat Mata ki Jai. They are Modi’s greatest supporters, imagining a revival of the Mahabharat, the Bharat of the legends.

The problem with this grand vision is that it militates against the most enduring character of Indian civilisation, a deep respect and belief in diversity of life, cultures and lifestyles. Hindutva on the other hand is an outdated 1920s theory of ethnic nationalism built on a then common template of anti-western hegemony but cocooned from within western modernism. It veers towards counter liberal tendencies.

Hindutva in the public space has not been a glorious spectacle with lynching of poor Muslims going about their traditional business of dealing with cow carcasses etc. In the new paradigm of India’s national identity, the cow has become more sacred than human life. India is increasingly becoming the land of Hindu and bovine rights.

Anti-Muslim sentiment, a fundamentalist type Hindu revivalism putsch against other Hindus, and the failure to make ‘lower’ castes inclusive have not endeared the Hindu voter whose understanding of a resilient Indian dharma is an ideology of pluralism rather than hate and intimidation. BJP’s reconstructed ‘Hindu identity’ has not only marginalised some minorities with sense of not belonging but challenges the very powerful essence of an enduring civilisation that has survived numerous efforts in history to force a monolithic outlook. It is highly unlikely that RSS-BJP will succeed where Moghuls and British failed.

Consequently, BJP’s attraction has waned as a post-Congress visionary party. Its economic record does not overcome its ideological handicap. Large number of Indians are reverting back to fissiparous politics. The ‘national’ idea is not appealing enough to hold itself.

The BJP will win but not the big majority it gained in 2014. Its asset is a ‘national cadre’ that can still revive some political ‘Hindu nationalism’. But its greater asset now is the ideological vacuity of a disparate opposition who the voter thinks will engage in palace coups as soon as they get into power. As Modi has pointed out several times, the only glue holding the loose coalition is ‘vote Modi out’, hardly basis of a national or economic manifesto.

India’s political issues are complex. Three dimensions stand out and continue to influence the oscillation between a ‘national’ surge and then falling back towards a default fissiparous politics.

Politics is forever engaged between an attempt to create an India wide and even worldwide Hindu identity in relations to others. The problem with this is that it is based on a negative concept. Both the words Hindu and Hinduism are terms of exclusion coined by invaders. Hindu was created as a general term for non-Muslims by Islamic invaders while ‘Hinduism’ as a broad tent term to include all Indian belief systems that lacked a clear indigenous name such as Sikhi or Buddhism, was introduced by British invaders. There is no real indigenous political theory that can merge from these political terms, hence reliance on western political paradigms.

The second is that Indian political thinkers continue to confuse civilisation with nation. The ‘nation’ as a concept is a European development based on meta ethnic community dominant in a State and based on exclusion. The ‘nation’ as a concept is in crises as the European State is becoming multicultural and multi ethnic and there is no mechanism within theory of nation to cope with this. By emulating the European idea of nation, Indian politics falls into similar crises.

Since 1947, Indian political thinkers have been attempting to ‘construct’ the ‘nation’ even though it has no relevance in the Indian State. Politics sees a surge for one party or person every couple of decades as a ‘new national’ identity is attempted either from the basis of external threat (war) or internal threat (fear of disintegration or marginalisation). Neither is sustainable, hence falls apart.

The Third is that the real Bharat is essentially a State of several nations, communities and immense plurality that has resiliently survived a few thousand years. But Indian political thinkers and parties remain in denial of this. Once the seduction of the ‘supra nation’ vision deflates from its own contradiction, the default fissiparous politics takes over. But no one has come up with a grand idea for a federal and fissiparous politics as a sustainable and constructive force.

The BJP-RSS idea of the mythical ‘nation’ has not found much unifying appeal beyond the cadre, the Indian Brexiter and the Hindu Khalistani abroad. People nevertheless are not enthusiastic about the opposition coalitions either. There is no convincing grand mythical ‘national’ idea dominating the election that can override the economic woes of people this time. Hence Modi is likely to win but not with the margin he got last time.

]]>