When it comes to what is happening in Ukraine, the discourse in Indian media, among its politicians and in the noisy environment of social media is all about one thing: how the 20,000 Indians, mostly students, were being evacuated back to India as the Russian military attack there gained momentum. If your news sources were solely Indian, you’d be bombarded with information on what the government was doing to get back its citizens from what was becoming a war zone.

The political capital to be gained from making a huge fanfare of the evacuation is obvious. Prime Minister Modi has had widely publicised interactions with Indian students who have come back home. His ministerial colleagues have chanted slogans that portray him as a sort of saviour.

Some of his ministerial colleagues have also provided us with a bit of comic relief. The civil aviation minister, who is known more for his sense of entitlement than any modicum of humility, went to Romania where Indians fleeing Ukraine had been sheltered. The minister was ostensibly overseeing their evacuation to India but true to his traits, he launched into a bombastic speech. It was interrupted by the Romanian mayor of the city who pithily told him that it was he who had provided the fleeing Indians with food and shelter and not the minister whose job it is to take them home. The entire episode, caught on video, went viral much to the chagrin of the Indian government.

It is not anybody’s case that during crisis situations such as the one in Ukraine governments should not put in every effort to evacuate its stranded citizens. It is their duty to do so and they should. But to use such attempts to boost the popularity of a political leader or to squeeze political benefits from such moves is in pretty poor taste. But then taste or finesse has not been the hallmark of India’s ruling regime. Instead, it has usually appalled us with its reactions and responses to developments such as the one in Ukraine. When the focus was on the evacuation project, hubristically named Operation Ganga, some political leaders criticised Indian students for going abroad to study and not stay in India.

Such loonies abound in Indian politics and public life–recently a well-known TV host who had two foreign guests on his show carried on berating one of them not realising that he was mistaking him for the other person on the show. Instead of directing his rant at the American foreign policy commentator, he aimed his high-decibel rant at an Ukrainian journalist and carried on doing it till the hapless journo could protest and set things right.

The more intriguing question about how India, its government, its political leaders and its media are handling the Ukraine crisis is about why the Indian official reaction to Russia’s aggression in Ukraine has been so muted. Last week, the three other members of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, colloquially the Quad or QUAD, which is a strategic security dialogue between the United States, India, Japan and Australia, urged India to join the rest of the group in condemning the aggression in Ukraine. But India hasn’t complied yet. It is among the 35 nations that have abstained from voting on a United Nations resolution against the Russian attack.

As the world’s most populous democracy, India needs to be a bit more assertive on the global stage. In recent times, the country’s leadership has demonstrated episodic reactions to global developments. With Russia India has enjoyed favourable trade and investment relationships that date back to the Soviet era. And Russia continues to be the largest supplier of defence equipment and arms to India. But when a country like Russia is aggressive towards another, much smaller nation, is it not time for India to condemn such a move? Or is it that in the new world order, India has begun to take sides and align with a new superpower? If that is the case, there could be another corollary question: If another powerful neighbour of India–China–decides to get a bit aggressive on India’s eastern border, what kind of support does the country expect from other nations, including Russia? India should ponder that.

Time for poll results

Be prepared to be assailed by a barrage of exit polls, some of which will undoubtedly be wide of the mark. After March 7 when the last phase of the Uttar Pradesh elections are completed, marking an end of elections in five states–Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Uttarakhand, Goa, and Manipur–the speculation about who will win in these states will be swirling around in discussions in social media and mainstream media, of course, but also among India’s ordinary citizens. Elections are the most secular festivals in India, even as the other “real” festivals get more and more communalised.

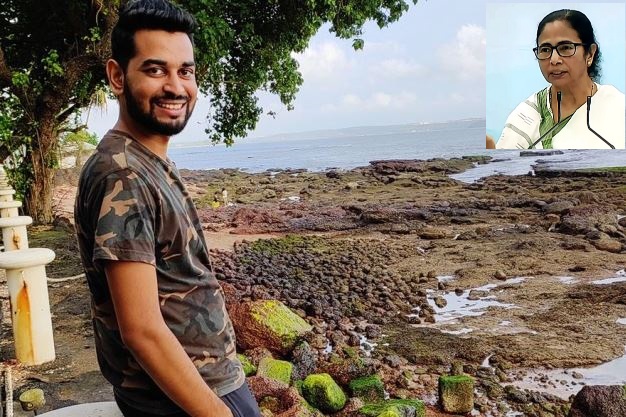

While it will be foolhardy to predict who is going to win in these states–even seasoned analysts quite often get their predictions wrong–it may be worth the while to keep in mind a few issues that could be important. First, in Uttar Pradesh, would the BJP win again? And if it does, would it scrape through or have a decisive victory? Also, would the highly divisive hardcore Hindutva proponent, Yogi Adityanath, get another term as chief minister? In Punjab would a relatively newcomer party, Delhi’s Aam Aadmi Party manage to top the scale when the results are out? That could mark a breakthrough for its leader, Arvind Kejriwal? And then, of course, it would be interesting to see whether Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee and her party, the Trinamool Congress, makes any headway in Goa. On March 10, we will know it all.