Since May 2014, after its victory in the Lok Sabha elections, the BJP as a party, and the BJP government in New Delhi, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Union Home Minister Amit Shah, has been in ‘election mode’. Critics say it was this “obsession” for electoral victory that the government completely missed the deadly ‘second surge’ of the killer Covid-19 pandemic and failed to ramp up the healthcare infrastructure in time.

After a brief pause, the party leadership is once again switching to the ‘election mode’ with an eye on the coming Uttar Pradesh elections next year. For Modi and Shah, winning UP seems the last straw amidst a rapidly falling popularity graph.

However, the drubbing in West Bengal continues to rankle. Not only because ‘Didi’ has emerged as a ‘national icon’ after her incredible victory with Modi as her principal political opponent. But because she is tipped to be a possible leader of a secular opposition alliance in the next Lok Sabha elections.

Mamata Banerjee is not unaware of her new status. One can clearly witness that every political move of Didi since her victory on May 2, is designed to position herself as a ‘direct adversary’ to Modi, while attacking him routinely with an aggressive and creative consistency. This is bound to unnerve the ‘Dear Leader’ in New Delhi.

Take, for example, her statement after what seemed like the hounding of her chief secretary by the Centre on whimsical grounds: “There are so many Bengal cadre officers working for the Centre; if we confront like this, what will be the future of this country, Mr Prime Minister? Mr Busy Prime Minister, Mr Mann Ki Baat Prime Minister… what, do you want to finish me? Never, ever…. As long as people give me support, you cannot…”

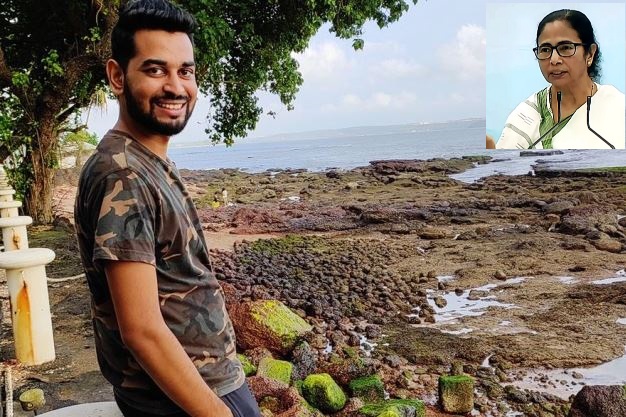

The latest is the ‘big news’ of what seemed a predictable event – the return of prodigal son Mukul Roy, back into the Trinamool, which he founded with Mamata Banerjee in 1998 against the mighty CPM which ruled Bengal for more than 30 years. Undoubtedly, this was ‘breaking news’ not only in Bengal, but in the national scenario.

Mukul Roy was the second-in-command, responsible for organizational affairs in the Trinamool, appointed as Union Railway Minister at the behest of Mamata Banerjee, her point-man in Delhi’s power circles, even while he called the shots in Kolkata. All this changed after the Narada-Saradha scam, and the decline in his fortunes led him into the lap of the BJP – also perhaps because that was the only alleged ‘method’ to escape the Centre’s law enforcement agencies.

Mukul Roy was seemingly sidelined before the assembly polls in the BJP though he was the key strategist who lifted the BJP to 18 Lok Sabha seats in 2019, an unprecedented victory in Bengal for the Hindutva party.

Roy shared this ‘scam dilemma’, along with another high profile ‘turncoat’, Suvendu Adhikari, who switched over to the BJP before the 2021 polls, became a bitter enemy of his mentor, abusing her in the most communal and misogynistic language during the campaign, and is now reportedly a favourite with the Modi-Shah dispensation, adding to the angst and anger of the ‘original’ BJP workers and leaders like state party chief Dilip Ghosh.

The inevitable return of Mukul Roy is therefore bad news for both Modi and Shah. In a party replete with discontent among its hardcore followers because it is filled to the brim with ‘turncoats’ — and several of them losing in the recent elections — his departure might trigger major defections back to Trinamool, including several MLAs. These defections are just a tip of the volcano – the BJP might be actually imploding in Bengal.

Indeed, with the BJP weakened in Bengal, and with Didi on the ascendant in terms of her ‘national stature’, it is believed by observers that all the signs are pointing to the beginning of the end of the Modi era, with a possible rainbow coalition of federal reassertion under a secular umbrella beginning to take shape in the national scenario. The latest is her move to send political strategist Prashant Kishore to meet Sharad Pawar, known for his tactical acumen; they had discussions for three hours.

Didi has called upon all opposition parties, including civil society organizations and NGOs to unite against Modi. Recently, in Kolkata, while yet again fully backing the farmers’ leaders who had come to meet her, she told journalists: “I have only one thing to say: Modi has to be removed from power.”

Besides, she told the farmers’ leaders that she will take the lead in organizing opposition leaders and chief ministers to hold a joint meeting in their support. Clearly, the importance she has been giving to the protracted movement and to specific leaders like Rakesh Tikait (the West Bengal assembly passed a resolution earlier in support of the farmers’ struggle), is evidence that she understands the political importance of the farmers as integral to future electoral dynamics, especially in the Hindi heartland, Haryana and Punjab.

Meanwhile, nursing the wounds of the massive defeat despite pumping in money and muscle, and the media hyperbole, the Modi-Shah regime started hounding Mamata Banerjee soon after May 2. First, there was this fake news campaign of organized violence against the BJP cadre and Hindus, with fake videos and Whatsapp campaigns trying to create a communal divide. She was blamed by central leaders, but the fact is that when the short-lived violence was triggered, the Election Commission was still in control, the central forces were still deputed in Bengal, and she had not been sworn in as the chief minister.

She took over, gave compensation to the victims across the political spectrum, and ordered a complete end to the violence. The violence stopped, even while Bengal celebrated the incredible victory of the secular forces against hate politics, with a deep, quiet and discreet dignity, mostly indoors.

Soon after, two of her senior ministers and two top leaders were arrested by the CBI, for being involved in the Narada scam. Mukul Roy and Suvendu Adhikari, also accused in the same scam, were left untouched. This was followed by the hounding of her chief secretary by the Centre, post Cyclone Yaas, for what seemed like a whimsical revenge act. Even the Congress and the CPM in Bengal criticized this, and there were rumblings within the BJP that this is indeed a terrible move by the Centre.

All this has been reinterpreted in Bengal and the rest of India as a display of arrogance and power, even while the feisty and resilient ‘Didi’ emerged yet again as a mass leader, street-fighter and formidable adversary against Modi. The more they hounded her, the more she has become popular, emerging as a ‘national icon’ who decisively took on Modi – and defeated him in his own game.

Clearly, as of now, it’s a win-win scenario for Mamata Banerjee. In a country where the Constitution and its federal structures have been so deliberately weakened in contemporary India, her brave and steadfast reassertion from the East might mark the rise of a new dynamics in mainstream politics in the country.